Most Philadelphia neighborhoods still haven’t recovered from the recession

Despite a recent building boom, Philadelphia’s housing market has not recovered from the Great Recession, especially outside Center City.

(PlanPhilly)

Despite a recent building boom, Philadelphia’s housing market has not recovered from the Great Recession, especially outside Center City.

While new high-rises are going up downtown and a handful of neighborhoods like Fishtown are gentrifying, the market in much of the city remains cool, a new study of mortgage data released this week by the Reinvestment Fund shows.

“A lot of attention is paid to the very high-flying neighborhoods of Philadelphia. What these data point out is that these communities are just a small fraction of the greater part of Philadelphia, which has really not recovered from the recession,” says Ira Goldstein, president of the Reinvestment Fund, who wrote the report with Michael Norton, the organization’s chief policy analyst.

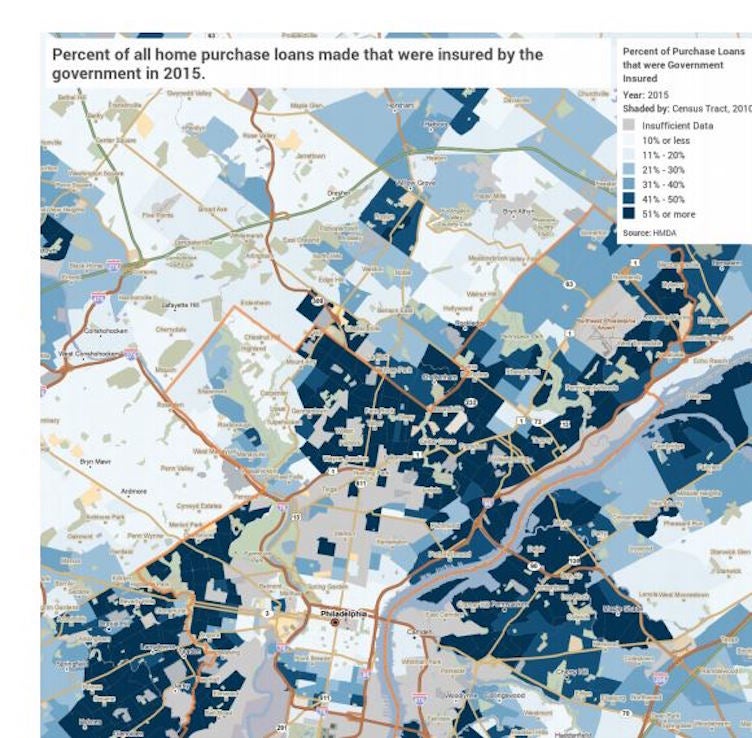

Goldstein and Norton looked at data released to the federal government by financial institutions. They found that conventional mortgage lending remains strong in Center City communities, in a handful of surrounding neighborhoods, and in areas like Chestnut Hill and Roxborough.

But throughout much of the rest of the city, both lower-income and middle-income neighborhoods, people are having a hard time getting conventional mortgages. Researchers found that for immigrant neighborhoods and communities of color, the credit crunch is especially acute.

Unable to rely on conventional banks, aspiring homeowners have turned to the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veterans’ Administration (VA). While these loans help borrowers get into homes, they come with more expenses than conventional mortgages.

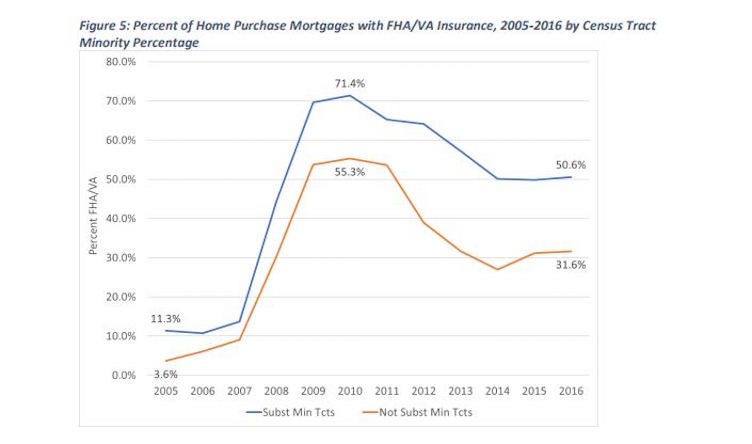

Before the Great Recession, federal agencies backed less than 5 percent of mortgages in majority white neighborhoods and just 11 percent in majority Latino or African-American areas. That percentage shot up dramatically in the years after 2008, reaching a peak in 2011. Today in African-American and Latino majority neighborhoods FHA and VA products still dominate the market, providing over half the mortgages for those who live in these areas. In majority white neighborhoods FHA and VA mortgages have dropped to 31.6 percent of the market.

These are important signs of progress, Goldstein says, but more recovery is needed.

“We want to get back to a place where conventional credit is flowing into communities along with government-backed products so that they can have a full array of financial products supporting their markets,” says Goldstein.

Areas as disparate as East Mt. Airy, Oxford Circle, and parts of the Far Northeast are seeing similar government dominated lending activity and a sluggish conventional market. In many of these areas, the weak mortgage market goes hand in hand with elevated rates of foreclosure, eviction, and stagnating home prices.

But the Reinvestment Fund’s report provoked skepticism in some quarters as well. Philadelphia-area realtor David Feldman, who teachers housing policy at Temple University, argued that the disparity between FHA lending in 2005 and 2015 shouldn’t be too alarming. After all, in the mid-2000s some policy analysts were musing about whether the FHA was still needed because conventional lending was reaching more people–but in a way that proved to be dangerous.

“2005 isn’t a market we should try to replicate, that’s when there was predatory lending and mortgages given to people who shouldn’t have qualified,” says Feldman, president of Right-Sized Homes LLC. “These numbers are interesting, but is it a bad thing to have so much FHA in a market like ours with cheaper homes and lower incomes?”

The concentration of government-backed mortgages in communities of color represents a reversal of the role these agencies played in their mid-century heyday when they favored strictly segregationist lending patterns and discriminated against African-American neighborhoods in North and West Philadelphia (as well as other older urban areas populated by immigrant or Jewish communities).

But today, many of the communities where government backed mortgages are dominating the market are in outlying areas that have long been the backbone of Philadelphia and its tax base. They kept the city together even as Center City and its environs were in decline during the latter half of the 20th century.

Feldman says that the study shows how important these federal institutions have been for Philadelphia.“It shows how if it wasn’t for FHA we wouldn’t have rebuilt our marketplace,” says Feldman.

It also shows that the market in these areas may not be hot, but that means it is affordable to many Philadelphians.

“This [report] adds a layer of understanding to what’s happening on the ground in the middle markets,” says Feldman. “It shows that we don’t need to worry about people with workforce jobs being priced out of [most of the city]. We still have a lot of housing like that, people are buying it, and this is the product–even though we could use more products for moderate-income buyers.”

The data examined by Reinvestment Fund comes via the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), a consumer protection measure put into place in 1975 as a response to redlining and other discriminatory or predatory lending practices.

The Reinvestment Fund analysis concluded that while latest trove of data makes it clear that access to credit remains uneven across racial lines, more investigation is needed to determine whether disparities are due purely to economics or if discriminatory lending practices are also in play.

That investigation is not likely to be helped along by Washington. The Trump administration has rolled back enforcement of HMDA reporting requirements and officials have said that they intend to reconsider updates to the act place by Obama administration. Soon after taking office, Trump also suspended a planned cut to FHA premiums that would have saved borrowers as much as $1,000 a year or more.

With little help expected from Washington D.C., Goldstein and area residents say local government needs to keep an eye on vulnerable homeowners and their neighborhoods.

“There needs to be purposeful attention paid to what happens in those communities from our city officials,” said Goldstein.

After all, Goldstein says, the city’s tax base is its homeowners and most of them don’t live in Center City or areas like Fishtown.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.