How should we talk about monkeypox? Local experts say tailoring public health messaging is a balancing act

Monkeypox has sparked a debate on how to recognize its disproportionate impact on LGBTQ communities in a non-stigmatizing way.

File photo: A visitor checks in at a pop-up monkeypox vaccination site in California. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

A large-scale global outbreak of monkeypox has forced countries and communities to address a virus that they’ve never, or seldom, seen in the past.

It’s led to confusion on who is most at risk, how and to what extent the virus spreads, and who should have access to testing, treatment and vaccination.

But it’s also sparked a debate on how to recognize monkeypox’s disproportionate impact on LGBTQ communities in a non-stigmatizing way, and craft guidance for the general population without unnecessary alarm.

In Philadelphia, where there have been 198 cases of the disease, residents and LGBTQ leaders have expressed frustration over the state and city’s response to the health crisis.

So, how do we talk about monkeypox? It depends on who you ask. But one thing local residents, LGBTQ people and public health experts agree on — it’s complicated.

“What a difficult situation and fine line to be walking here,” said Dr. Perry Halkitis, a psychologist and dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health.

In the fear of getting messaging right, ‘we’ve gotten it wrong’

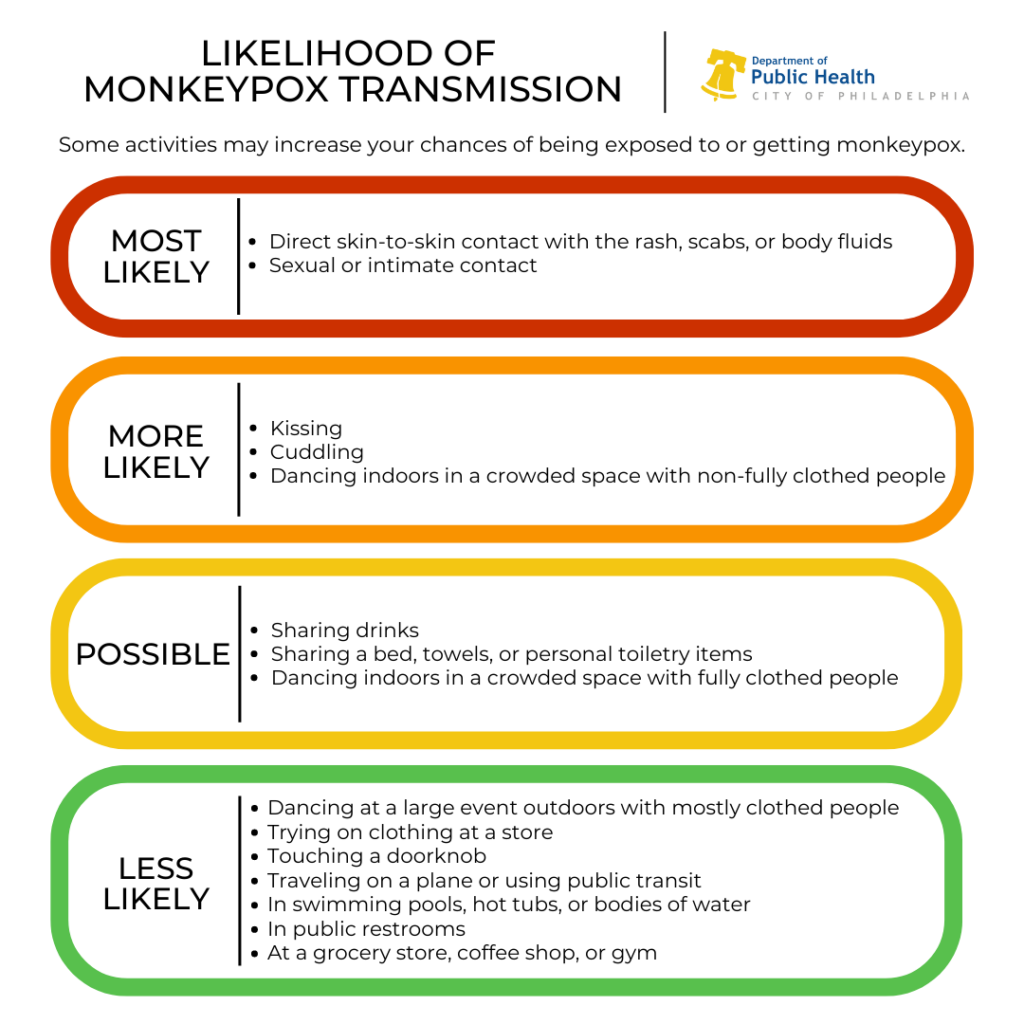

Health experts say prolonged skin-to-skin contact and direct exposure to a monkeypox rash is the predominant way that this virus is being transmitted from person to person, especially during sexual activity.

It can also be spread through contact with objects and materials, and respiratory fluids — but it’s unclear what role those modes of transmission have played in the current outbreak.

Global studies have found the vast majority of cases so far have been identified among gay and bisexual men. Though, they say, anyone can become infected, and there’s a lack of data showing to what extent exactly the virus has spread in the general population.

Halkitis, an author and researcher whose work has focused on LGBTQ-centered health care and HIV/AIDS, said these unknowns have opened the door to flawed public health messaging.

“I think in the fear and the anxiety of getting it right, we’ve gotten it wrong,” he said.

Public messaging was vague and overly broad at first about who might be most at risk of contracting monkeypox and why. Eventually, a lot of messaging specifically focused on risk factors for men who have sex with men, particularly those with multiple, anonymous partners.

That focus in Philadelphia has helped get resources and a limited number of vaccines to high-risk residents in the LGBTQ community. But advocates say this kind of attention can also lead to stigma and discrimination.

Local and federal health agency leaders have said they intend to get resources to people who are being impacted the most, but Halkitis believes that sexual activity among LGBTQ persons, in the context of the monkeypox outbreak, has been mischaracterized.

“I’ve been calling monkeypox a disease of intimacy, not a disease of sex,” he said, “because then you make it about sex … and what you’re basically saying is that gay sex is bad and leads to disease.”

That’s the kind of framing that reminds Halkitis of the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, when people knew little about how and why the virus spread, but were quick to discriminate against gay, trans, and bisexual men who were, and still are, disproportionately affected by the epidemic.

Tailoring health guidance to a larger population

Max Ray-Riek, a Delaware County resident and HIV/AIDS educator with ACT UP Philadelphia, said he believes it’s important that health guidance and messaging be tailored to all different groups of people, not just queer people, especially since it’s unclear how easily the virus spreads beyond intimate contact.

“People who are not queer can and do, and are getting monkeypox,” he said. “And it restricts their access to testing, restricts their access to preventative vaccination and post-exposure vaccination.”

In the U.S., eight children so far have been infected.

Ray-Riek said one problem in health guidance so far around monkeypox is prevention and vaccine recommendations, which still largely focus on gay and bisexual men, and other adults who have sex with men.

He said it can be confusing for people who don’t neatly fit into those categories.

“[It] just doesn’t capture the people who are most at risk of monkeypox,” he said. “I’m a transgender man. I don’t know if I would be eligible for the vaccine or not, and I don’t know who’s going to be interpreting that on any given day.”

An opportunity to do better

The World Health Organization has also recommended that men who have sex with men should consider limiting their number of sexual partners to reduce their risk. But Ray-Riek said that may not be possible for people who do sex work in order to make a living.

He said isolation guidance for people who’ve been exposed and infected is also made with the assumption that people have permanent housing to isolate in, or a job that will enable them to work from home or take time off. Ray-Riek said that’s not realistic for a lot of people.

“If there’s one thing we learned from COVID, it’s that public health messaging is not enough,” he said. “There’s nothing that undermines public health messaging faster than not also providing the means to follow the guidance.”

Sebrina Tate said that implementing effective public health strategies, it comes down to having better partnerships with organizations that serve vulnerable communities, before a crisis hits, not just during.

Tate is the executive director at Bebashi, a non-profit organization that serves Black and brown communities with LGBTQ-focused health care and services.

“All of the information, how we receive information, how it’s broken down, digested and understood — how do you make it culturally sensitive so that people are making the best decision for their health care, the best decision for them, and protecting themselves the best way they know how?” she asked.

Tate said the window is closing to get it right, but there’s still an opportunity to do better.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.