Philly mayors have a mixed history of supporting the arts. Will the next one be an arts mayor?

The mayor’s support of the arts — or lack thereof — plays a big role in the cultural community’s success. Here's a look back at some highs and lows.

Listen 6:15

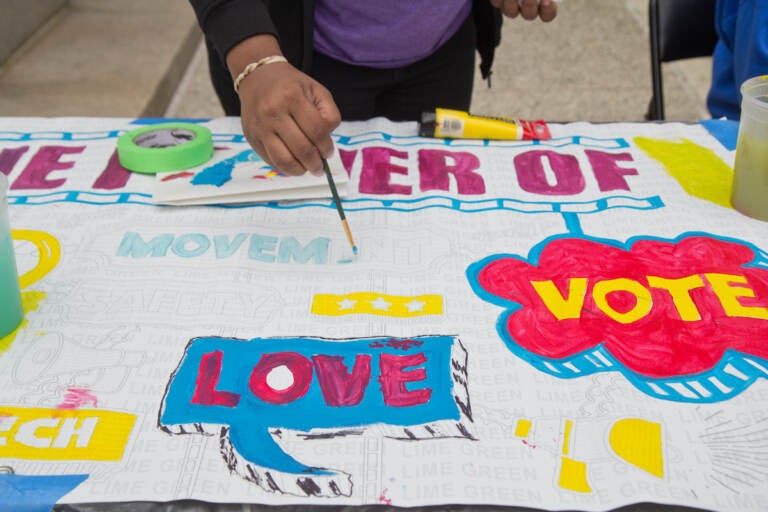

Philadelphia’s Mural Arts organization hosted a community paint project at the #fundPHLarts rally outside City Hall in Philadelphia on May 11, 2022. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

What questions do you have about the 2023 elections? What major issues do you want candidates to address? Let us know.

This story is a part of the Every Voice, Every Vote series.

On April 20, musical celebrities gathered on South Broad Street in Philadelphia to unveil plaques with their names embedded in the pavement of Philadelphia’s “Walk of Fame,” included people like Broadway actor Leslie Odom Jr., actor and musician Kevin Bacon, and local DJ Patty Jackson.

Among them was Ed Rendell, who admitted that he, as a person with no artistic talent, was in strange company.

“I always associate this with movie stars,” he said. “Not politicians.”

Rendell was given a special honor for pushing the development of the Kimmel Center and envisioning the Avenue of the Arts — a portion of South Broad Street lined with theaters, restaurants, and concert halls — when he was mayor in the 1990s.

Some have called Rendell the “arts mayor” for the way he leveraged the arts sector to revitalize Center City. As the May 16 primary election approaches and a new batch of candidates campaign to be the 100th mayor of Philadelphia, the arts sector is asking those candidates: “What will you do for the arts?”

Philadelphia mayors have been a mixed bag when it comes to the arts. Here’s a look back at some highlights.

The Philadelphia that Rendell inherited when he became mayor in 1992 was at the “darkest day in its history,” he said. The city was broke, and downtown was all but abandoned after dark.

Rendell decided one way to boost the city’s fortunes was to invest in the arts.

“But I had to deal with a $2.3 billion deficit. So I turned it over to the most competent person I’ve ever met in my life: Bill Clinton,” he said, joking. “No, no, Midge Rendell. I said, ‘Dear, you need to take this under your wing.’”

So Marjorie “Midge” Rendell, a federal judge who was the mayor’s wife at the time, set about making the Avenue of the Arts happen.

“When we were starting I said, ‘I’m going to get Ellen Casey, the wife of the governor’ — this is the power of women — ‘and invite her to a luncheon,’” she said. “We decided we were going to have a special cocktail party in her honor at Tiffany’s. She went home and — thanks to pillow talk — Governor Casey agreed to send $94 million our way for Avenue of the Arts projects.”

Of course it’s never that simple: it’s politics.

The head of the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance at that time, Cathryn Coates, needed to put the right pressure on the right people. She turned to a Philadelphia political operative, Henry “Buddy” Cianfrani, a former state senator who had recently been released from federal prison where he served time for corruption.

“We met with Buddy Cianfrani. We said, ‘How do we make the arts important?,’” Coates recalled. “He had this really gravelly voice, and he goes: ‘Get to Midge.’”

Coates got to Midge, but she also had to get to Rendell’s chief of staff, David L. Cohen, who is now President Biden’s ambassador to Canada.

“David L. Cohen was supremely annoyed that we were distracting Rendell with the arts. He thought it was a waste of time,” she said. “He finally bought in when he realized that it was not just about the money, it was about the image. It was about how people feel.”

“That was how Avenue of the Arts and the Philadelphia Cultural Fund happened: because Ed Rendell decided it was important,” she said.

Rendell has sometimes been called the “Arts Mayor” for his efforts to make downtown an arts destination. But he was not really an arts lover.

“Personally, he obviously prefers sports. When he talks about sports he’s a much happier guy,” said Coates. “It’s not like Ed Rendell liked going to the ballet — at all — but he understood the importance in a really meaningful way.”

Other mayors have also recognized the importance of the arts in Philadelphia.

Harry Mackey, the mayor from 1928 to 1932, created the Municipal Bureau of Music to ensure people could listen to music throughout the city.

The bureau did things like donate thousands of radios to hospitals, playgrounds, and community centers. It also created a musical car — a modified truck that could drive anywhere to play music in public places for dancing and recreation.

The Philadelphia Bureau of Music only lasted about three years, ending during the Great Depression.

In 1955, Mayor Joe Clark launched a city-wide arts festival that branded Philadelphia as an arts destination.

“Our city is nobly endowed with schools in every field of art, with outstanding art treasures and with widely valued art activities,” Clark said in 1955. “All of these are expanding rapidly and with a sensitivity to the spirit of our age which I believe will account for much of the city’s greatness in the future.”

About 50,000 people reportedly attended the festival, which was held three times in seven years, ending in 1962.

The first art program to be permanently baked into the function of city government came during Mayor Richardson Dilworth’s administration, with the launch of the Percent for Art program in 1959. That is where one percent of the cost of a municipal construction project, or a private development by acquisition of public land, must be spent on public art.

Since then, Percent for Art has been adopted by many cities around the country. Some observers say other cities administer their programs better than Philadelphia, with more funding and rigor.

“Many have observed that if the administration does not show support for public art, the percent requirement becomes negotiable, or agencies do minimal work to get Art Commission approval,” read a 2009 report by PennPraxis, “Philadelphia Public Art: The Full Spectrum.”

Art consultant Marsha Moss, who serves on the Mayor’s Public Art Advisory Council, said the Office of Arts and Culture, which administers one of the city’s Percent for Art programs, teeters with each mayoral transition.

“In its present status, the managing director may be directed by the next mayor to dissolve the office, as Mayor Street did in 2004, and Mayor Kenney almost succeeded in doing before the arts community voiced its protest,” Moss said. “What a devastating loss that would be for the city.”

The city Office of Arts and Culture was created by Mayor Wilson Goode after he took office in 1984. Even though Street eliminated it 20 years later, the arts nevertheless found a way.

Street created a new office of social services, into which he rolled various government departments like health, welfare, prisons, and Mural Arts Philadelphia.

Street put Estelle Richman in charge of it.

“People were very divided into silos,” Estelle remembered. “Every department wanted to focus just on their piece of it, and saw anything that they didn’t see directly related to what they were doing, as something they didn’t want to relate to.”

Richman saw that the arts could be a way to break department heads out of their silos, so she called Jane Golden, head of Mural Arts Philadelphia.

“I remember her reaching out to me and saying, ‘I’m a fan of Mural Arts and I would like to make Mural Arts part of the division of Social Services,’” said Golden. “‘I saw myself as being very low on the food chain.’ I was like, ‘You do?’”

“Then she called me into a meeting and I was with the commissioners of these big departments. She said to them, ‘I believe in the power of art, and I believe art should be part of how all of you do business.’”

Richman urged the department that oversees children’s health, for example, to use Mural Arts as a way to engage kids in healthy after-school programs. Art could be used to reduce recidivism rates in prisons. Richman pushed departments to think outside the box, and also share their most hard-fought asset: city funding.

“That was a little bit of a challenge,” Richman said. “I had to make sure Jane could explain it, which she did very well, but they had to understand this was a value added to them, not just giving something to her.”

Even though the Street administration killed the Office of Arts and Culture (later revived by Mayor Michael Nutter), that was when one of Philadelphia’s preeminent arts organizations, Mural Arts, found its footing.

“I credit Estelle and John Street for the huge growth in Mural Arts, and our ability to work with young people, to work in prisons, to work with the behavioral health system, to expand our art education efforts,” Golden said. “She was both aspirational and pragmatic. If it happened then, it could happen again.”

After working for Mayor Street, Richman went on to be welfare secretary for the state of Pennsylvania. Now she is back in City Hall working as a consultant for the Managing Director, building a coalition of public, corporate, and foundational partners to curb gun violence.

She hopes the next mayor — whoever it is — won’t dismantle that work.

“Philadelphia has this bad habit of a new mayor coming in, criticizing the old mayor, and throwing the baby out with the bathwater,” she said. “In some cases they’ve thrown out the baby, the bathwater, the bathroom, and half the house. This goal is to stop that.”

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.