How Philly’s next mayor may rely on arts groups to address civic problems

Mayoral candidates say they want to use the arts to address civic problems. Some even see it as an important part of anti-violence work.

Listen 5:13

Michael Barnes embraces his 13-year-old son, Elijah, behind a drum set at the Clef Club. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

What questions do you have about the 2023 elections? What major issues do you want candidates to address? Let us know.

This story is a part of the Every Voice, Every Vote series.

At a recent mayoral forum in Philadelphia, a somewhat unexpected question came up. Several candidates were asked how, in their administrations, the arts would be used as a violence disruptor.

All eight of the candidates who gathered on March 30 at Taller Puertorriqueño, a Puerto Rican cultural center in North Philadelphia, said they envisioned using the arts sector to address city problems.

“Arts are an important part of anti-violence work,” said candidate Rebecca Rhynhart, citing her involvement with Mural Arts Philadelphia. “I’ll make sure that the arts are used to address many of the issues facing our city, whether they be violence, whether they be homelessness, whether they be mental illness.”

Another candidate, Helen Gym, agreed, citing her own work with the Juvenile Law Center and the Youth Art & Self-empowerment Project (YASP).

“[It’s] about anti-violence work, absolutely,” Gym said. “But mostly about bringing people – especially young people back to life and back to a feeling of their own humanity and fulfillment of their own potential.”

In the run-up to the primary election on May 16, Philadelphia arts leaders have been pressing candidates to think seriously about the city’s arts and culture sector. The Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance released a 5-point policy platform, including a demand for a coherent arts plan “that will be implemented across city agencies/departments to stimulate economic recovery, enhance urban livability, and reshape the vitality of Philadelphia.”

The head of the GPCA, Patricia Wilson Aden, cited a film project that is aimed to curb gun violence created by First Person Arts, an organization that helps people tell their own stories.. The documentary “Trigger” uses first-person narratives to describe the trauma of gun violence.

“We’re hoping our next mayor understands and appreciates arts and culture as a tool to make change as a problem solver,” said Aden. “There are so many instances where arts and culture has proven to be a vital change maker, so it is not a nice thing to do. It is not an amenity.”

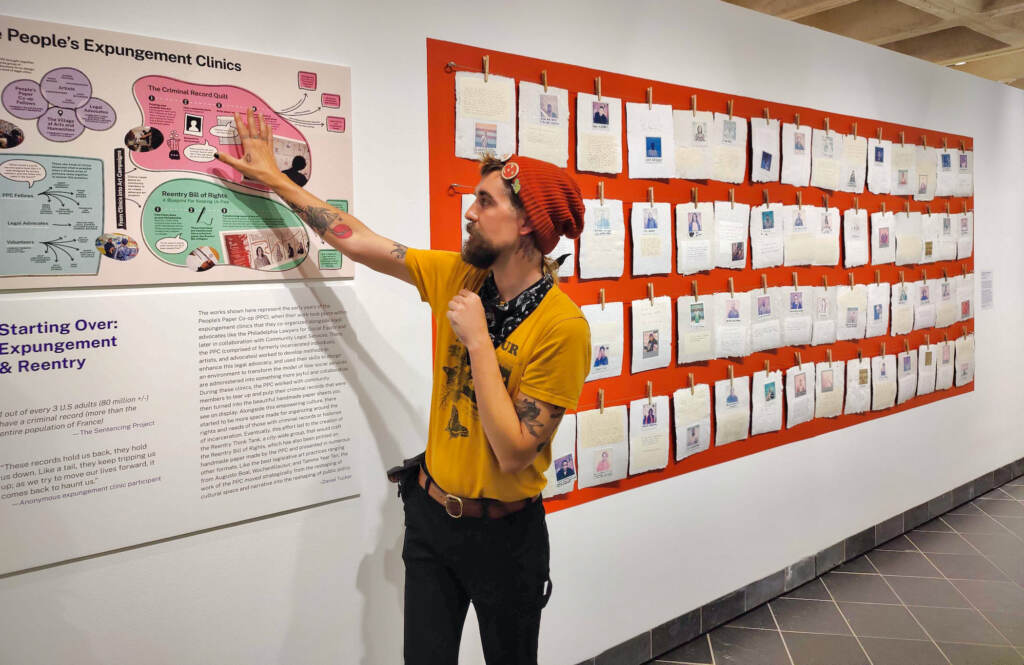

Another example is the People’s Paper Co-op, an initiative of The Village of Arts and Humanities, uses art to engage people in a workshop to get their criminal records expunged. People are invited to render their old criminal records to paper pulp, from which new paper is made on which they can imagine their future lives.“If what we’re dealing with now, with our systems and institutions, is not working for so many people, art is a beautiful way for us to imagine a different way of working,” said PPC co-founder Mark Strandquist. “It just gets to a deeper place than almost any other form.”

Michael Barnes’ life was also has deeply changed by the arts. He grew up in Germantown in the 1960s and 70s when he developed a musical talent for clarinet and saxophone. He took classes at Settlement School and the old Combs College of Music when it was based in West Mount Airy.

“I remember my mother breaking the piggy bank so I could get my lesson in with the great John Russo,” Barnes recalled.

He pursued R&B and found a steady gig with the late-era Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. But when Melvin suddenly died of a heart attack in March 1997, Barnes felt the bottom fall out of his life.

“All of a sudden I had nothing,” Barnes said. “So I panicked a little bit. I started drinking. And that night the car went out of control.”

The night was November 8, 1997, when Barnes sped recklessly along Ridge Avenue near Hunting Park. According to a police toxicology report, in his system was twice the legal limit of alcohol, as well as cocaine. He collided with a pole, resulting in the death of one of his passengers, and serious injuries to Barnes and two others.

Barnes was sentenced for vehicular manslaughter and a handful of other charges, and served time in a few state prisons before landing in SCI Chester, where he saw a familiar face: longtime Philly jazz composer and saxophonist Bobby Zankel, whom Barnes had previously met on the Philly music scene.

Zankel worked as a music teacher inside Chester, a job he held for 20 years. His prison jazz program is featured in a video from a TEDx talk held inside the prison in 2016.

“The jail had instruments,” Zankel said. “I’d teach them to read and they would come in each week and we would play.”

Zankel said most inmates were able to become proficient on guitars and keyboards because those instruments were allowed in cells. Horns were off-limits outside Chester’s music room. Because Barnes already knew how to play saxophone, he fit right into the jam sessions.

“He played with Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. He was a good saxophone player,” Zankel said. “He didn’t know certain things about jazz. He was more of a R&B player, but he had a beautiful sound. Still has a beautiful sound.”

Zankel took Barnes under wing and shaped him into a jazz man.

“He said, ‘Mike, I’m going to teach you about being a man of integrity,’” Barnes recalled. “Meaning when everything else, everybody else is doing wrong, that I’m doing right.”

“He was a very integral part of reshaping what was an alcoholic criminal-type guy, you know, instead of just the music,” he said. “I didn’t need substances to make me play better or feel better.”

Barnes and Zankel are both out of SCI Chester: the former released in 2017, the latter retired in 2016. But they still come together every Saturday at the Philadelphia Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts, a music education and performance venue on South Broad Street.

Barnes sends his 13-year-old son, Elijah, to the Clef Club to play under Zankel. It’s not just to make him a good musician: Barnes has seen the pitfalls of growing up in Germantown and “the element of the corner,” noticing a lot of his son’s friends don’t have positive male role models in their lives.

“You have four or five friends your age, they’re going to come at you with an idea: Let’s go break out a window or let’s go steal a car or let’s rob somebody,” Barnes said. “If they’re at a place like the Philadelphia Clef Club where they can come on Saturday and apply themselves to some music education and just learn a little something, they’ll grow.”

Zankel teaches a jazz ensemble on Saturday morning, training promising young players On a recent Saturday, the students came from as far as New Jersey and Delaware County.

“This program has turned down some of the most important musicians in America. The guy on TV five nights a week is from the Clef Club – Questlove,” said Zankel, referring to Amir Thompson, co-founder of The Roots, the house band for the Tonight Show. Also jazz greats like Christian McBride and rising star Immanuel Wilkins.

“There’s a list of people who are major American musicians that came to this program in the last 30 years,” said Zankel. “So if you had a son, it would be in a natural place if you wanted him to be a musician.”

Zankel’s players mostly perform Zankel’s own compositions, which often have rhythms with challenging intervals.

“There are ‘intervalistical’ things I do that are not what the kids are used to,” he said, using a uniquely derived word that the kids are also not used to. “There’s a lot of rhythmic ideas that I do that are not what they would get in any school band. I’ve learned about rhythm. I’ve been really blessed with the mentors that I’ve had. I’ve really learned some interesting things.”

Now, Barnes’ son Elijah plays drums for Zankel’s Saturday morning jam session, and bounces between the practice rooms for different classes all day. Barnes hopes his son will benefit from the same music instruction he had while in prison.

“When you’re incarcerated in these places, you run into people – they don’t even know you and they just hate your guts. They come after me,” he said. “When the music was starting to play inside the facility, there was less activity of violence. It was people talking to one another and associating with one another on a higher level.”

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

This story is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute, Peter and Judy Leone, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Harriet and Larry Weiss, and the Wyncote Foundation, among others. Learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters here.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.