How one Philadelphia teen shooting survivor navigates trauma and recovery with family and friends by his side

Trauma that comes from directly or indirectly experiencing gun violence can have short- and long-term effects, especially among youth survivors.

Listen 6:03

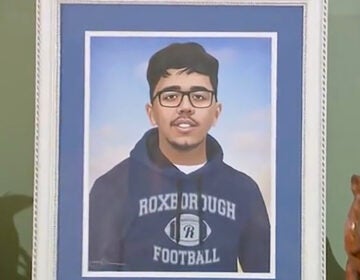

18-year-old Ivan Cuevas survived a gun shot to the head nearby his school in Northeast Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Gun violence in Philadelphia takes a toll on students and their ability to learn and succeed. WHYY News’ gun violence, education, and health reporters look at the intersection of schools and violence in their new six-part series, “Safe Place.”

Four teenage boys crowded around a small table in the living room, intensely focused on the Uno cards in their hands.

It was a Sunday afternoon, and they were at Ivan Cuevas’ house in Northeast Philadelphia. The boys have known each other since they were about 10, and the card game has always been their thing. They played in teams of two.

“UNO!” Ivan shouted, and looked to his teammate Joey.

“Whoa, whoa, whoa,” the other boys shouted.

“I was about to change it to green, bro. We just lost!” Jaymeir said as he turned to his teammate, Jalil.

WHYY News is withholding the teens’ last names because they are minors dealing with trauma.

The boys used to go to Jean’s Pizza and Grill, across the street from Abraham Lincoln High School, after class to eat and play Uno. On Oct. 18, 2021, Ivan was standing outside Jean’s with some of his classmates right after school when they heard the sound of gunfire nearby.

Everyone ran in different directions. But before Ivan could get far, a bullet struck the back of his head, landing millimeters from his brainstem, which regulates most of the body’s automatic functions, like breathing and heart rate.

Ivan spent about a month in the intensive care unit at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children. When he should have been out celebrating his 17th birthday, he was lying in a hospital bed hooked up to tubes and wires on life support.

His injury was so critical that doctors didn’t think he was going to make it. And if he did, they said, he might not walk again, let alone hear or speak.

Meanwhile, Ivan’s family — his mother, Natali Rosario, her fiancé, Rhiannon Hope, and his siblings — were experiencing a different kind of trauma.

What made it even harder, Rosario said, was watching the devastation play out among her son’s closest friends.

The day of the shooting, the boys sat in hospital waiting rooms, crowded the hallways until they were ushered outside, and even lingered in the hospital parking lot for hours, refusing to leave even when their parents pleaded with them to come home.

“I got sick, I cried so much,” Joey said.

Ivan was one of 212 kids who was a primary victim of gun violence in Philadelphia that year. Another 217 kids were primary victims of gun violence in 2022, according to city data.

Ivan’s friends were among the hundreds — maybe even thousands — more kids across the city who could be considered secondary victims as they have suffered trauma from the harm to or loss of friends and family.

Shootings, whether experienced directly or indirectly, can have short- and long-term psychological effects that can affect a child’s behavior and ability to learn.

University of Pennsylvania psychologist Dr. Caroline Watts said some students may need more help than others, because they develop a chronic fear of violence.

“Kids don’t expect to live past a certain point in their lives,” she said. “And most of the kids who say that are living in communities where they see kids just older than them killed.”

That fear, anxiety, or trauma can take a toll, said Dr. Shannon Stanford, clinical director of the Dr. Ala Stanford Center for Health Equity. And kids and teens don’t always recognize when it’s happening, she said.

“They’re not aware of the effects of stress, they’re not aware of the effects of trauma,” Stanford said. “They lack the language and they lack the understanding of how these things are actually impacting their bodies, their minds, their realities.”

In Philadelphia, students get behavioral health and trauma support services through a patchwork of school-based counselors and specialists in the community who supplement that care.

After this past summer, the school district assigned additional counselors to schools in communities that saw some of the highest rates of gun violence. Dr. Jayme Banks, the school district’s deputy chief of prevention, intervention, and trauma, said she hopes to increase the number of those positions going forward.

Students can speak with these professionals on a day-to-day basis. Every school in the district is also partnered with an outside health care organization that provides psychologists and other professionals who specialize in mental and behavioral health, for students who need more intensive care.

In the immediate aftermath of something like a shooting near or on school grounds, the district will often bring in experts who are specifically trained in providing mental health trauma care, Banks said.

Even with all the resources available, Stanford said, some kids still fall through the cracks and don’t get the help they may need. A stronger referral process within the schools and even more partnerships and connections with community health providers could help, Stanford said.

While Ivan was in the hospital, undergoing surgeries and treatment for his injuries, his friends missed at least a week or two of school as they struggled to process what had happened. They said they couldn’t concentrate on anything else.

Jaymeir said he didn’t go back to Abraham Lincoln High School for almost a month.

When the boys returned to class, they said the school offered them counseling services in recognition of their close friendship with Ivan and his prolonged absence. They all turned it down.

Jaymeir said his mom offered to take him to therapy, but he turned that down, too.

“I just wasn’t ready to talk about it,” Jaymeir said. “It’s still kind of hard for me.”

For Ivan, he had to first focus on getting out of the hospital and recovering from his physical injuries.

Ivan had to re-learn how to eat, walk, and talk. He had to work on his coordination.

He still suffers from slight paralysis on the right side of his face, and has complete hearing loss in his right ear. He said he’s not as good at playing basketball anymore, but he still gets out on the court with his friends from time to time.

It was while Ivan was in physical therapy that he began to feel angry about what happened.

“It was like, why me?” he said. “That was, like, the main event — why me?”

Over time and with support from family, friends, and medical experts, Ivan was able to let that anger go.

“You can’t stay mad forever,” he said, sitting on his living room couch. “I don’t know what else, but you just can’t stay mad forever at the situation, because there’s nothing you can do about it.”

His mother hasn’t quite reached the level of acceptance her son has. Sometimes, Rosario has small panic attacks and suffers from post-traumatic stress. She has to drive through the intersection of where the shooting happened nearly every day, and doing so causes her distress.

Rosario said she’s still angry.

And the trauma was prolonged every time she and her family had to go to court for hearings about the shooting. Aaron K. Scott, 22, pleaded guilty to third-degree murder and aggravated assault for shooting Ivan and killing another man.

Scott was sentenced to 30 to 60 years in prison just last month.

Aside from the court hearings and the rehabilitation, much of Ivan’s life has returned to normal. He hangs out with his friends or girlfriend, has an after-school job, has plans to go to senior prom, and then graduate in the spring.

But Ivan’s friends said little things have changed. They know what it’s like to almost lose a close friend. They’re more cautious of their surroundings. And still, over a year later, they’re working through the aftermath of that day.

At 17, Joey said the shooting has certainly changed his perspective on what trauma looks like.

“I used to think trauma was like, when I was younger, was, like, losing a game. I was so mad, like, dramatic. Now that I see you can lose somebody like that,” he said as he snapped his fingers, “I look at everything way different now.”

Ivan said having a strong network of family and friends made a huge difference in his recovery, in making a return to Abraham Lincoln High School, in becoming resilient through his trauma.

He’s determined to not let the shooting define the rest of this life.

Ivan and his friends haven’t been back to Jean’s Pizza as a group since 2021. But they may return for a game of Uno — someday.

WHYY News’ Sammy Caiola contributed to this report.

If you or someone you know has been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia, you can find grief support and resources online.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.