To Cirque, or not to Cirque? Philly circus pros weigh in on Cirque du Soleil

Cirque du Soleil makes the North American debut of “Bazzar” in Philly, a city with a strong homegrown circus scene.

Listen 2:23

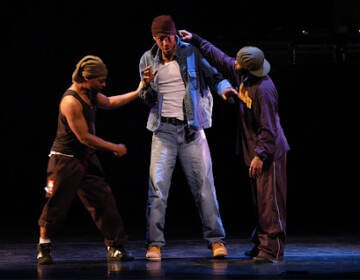

Trapeze artists perform in Cirque du Soleil's ''Bazzar'' at the Greater Philadelphia Expo Center in Oaks, Pa. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Cirque du Soleil has pitched its tents outside the Greater Philadelphia Expo Center, in Oaks, Pa., to stage the North American premiere of its COVID-delayed show, “Bazzar”.

Cirque is coming into a city that has a strong, homegrown circus scene: “Bazzar’s” big top was being set up just as the annual Fringe Festival was showcasing a particularly strong lineup of independent circus and clowning artists.

Ava Gowanloch, 21, a student at the Circadium Circus School in Mount Airy training to be a contortionist, performed in one of the Side C shows as part of the Fringe Festival. She saw an early preview of “Bazzar,” and said Cirque du Soleil is the Holy Grail of circus jobs.

“As a kid, before I got into circus, I was at the dentist office or something and it was just on the TV. I remember being so curious about it,” she said. “Now that I’m here training, that is like the end-all, be-all dream. That would be amazing to be a part of that company.”

“Bazzar,” loosely based on the colorful energy of Middle Eastern market bazaars, has already toured through India and Saudi Arabia. To better play in smaller venues available in the Middle East, it was originally designed for the small top, meaning spaces with smaller ceilings in which aerial acts relied in pulley systems operated from the ground.

“Bazzar” has been expanded into a big top, with taller tents inside of which a steel grid can be erected above the stage, enabling more complex rigging for aerialists. It was ready to start a U.S. tour in 2020, in New Orleans, when the pandemic shutdown forced it to close before it could open. Philadelphia has become the show’s North American debut.

On the ground, a clown known as The Maestro acts as the ringleader, walking through the audience to interact with them.

Excited audience members naturally want to take pictures and video of the show from their seats, which is allowed albeit without flash. But artistic director Johnny Kim is most impressed when audiences put their phones down.

“It’s breathtaking for me to sit back and watch people not put their phones up, but they actually put it down and enjoy the moment,” he said. “As much as we are always on our phones, it’s still beautiful to see these younger generations come to the theater and put their phones down and actually engage. I think that’s really important.”

Greg Kennedy used to be a juggler with Cirque du Soleil, helping create the now discontinued show Totem. For five years he toured with the company, his family in tow. He and his wife Shana then put down roots in Germantown and opened both the Circadium and Philadelphia Circus Arts schools.

He said his experience with Cirque was wonderful, but it’s not the “end-all, be-all” of circuses.

“I can’t say there’s one gold standard. It really depends on what you want to do,” Kennedy said. “Most artists after doing 1,500 of the same show, that’s locked down by the head office and policed by the general stage manager – you want to be creative. You want to do new things.”

“Any little change that happens in the show is such a big process,” he recalled. “We used to think of it as rowing a tanker ship with a teaspoon.”

Kennedy came to juggling as an engineer, inventing contraptions to create new stage routines. He still has a studio in the Circadium building, a former Catholic church and school, where he builds juggling apparatus when he’s not maintaining the building.

His wife, Shana, does most of the business of running the schools. While the Philadelphia School of Circus Arts offers amateur and drop-in classes, Circadium is the only state-certified, three-year professional circus school in the United States. Shana is currently working to make Circadium an accredited education program.

There are right now no accredited circus schools in the U.S. People aspiring to professional circus performance careers must usually travel to Canada or Europe. Shana said she received her circus training in England.

“We committed ourselves to being a place that artists could not only come to have fun with circus but really to develop careers in circus,” she said. “We’re seeing a growing number of young people moving to Philadelphia, starting their careers here, building their companies here. You can see it in this year’s Fringe, but it’s really gonna grow from this point forward.”

Circadium launched in 2017 and Zak McAllister, of Texas, relocated to Philadelphia to be in its first class. He trained to be a juggler and graduated just as the pandemic made job prospects scarce. He said he has worked up other skills, like video production and lighting, but a juggling gig with Cirque du Soleil is still the brass ring.

“One of those jobs is so coveted,” McAllister said. “You have to be the best of what you do to get a job like that.”

Gowanloch, the contortionist, is in her second year at Circadium and also hopes to one day land a job with the biggest producer of circuses in the world: Cirque du Soleil currently has eleven productions touring the globe simultaneously, and nine stationary resident productions in Las Vegas, Orlando, Riviera Maya (Mexico), and Trois-Rivières (Quebec).

But having been in the Philadelphia circus scene for a little more than a year now, more possibilities have opened up to Gowanloch.

“Moving from Orlando, where there wasn’t much of a circus community, I moved here and entered this building and I was like: ‘Wow, there’s so many more opportunities,’” she said. “So many more people doing all kinds of different things. It’s really cool to see that.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.