A look inside the ‘Dreamworld’ of surrealism at the Philadelphia Art Museum

The art movement originated in France in 1924 and quickly began influencing all forms of media across the globe.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The day after the Philadelphia Art Museum’s surreal experience of watching its board suddenly fire CEO Sasha Suda, the museum turned its attention to a different kind of surreality.

Louis Marchesano – who has temporarily taken over day-to-day operations of the museum – would not comment on Tuesday’s earthshaking executive termination, instead focusing on surrealist art.

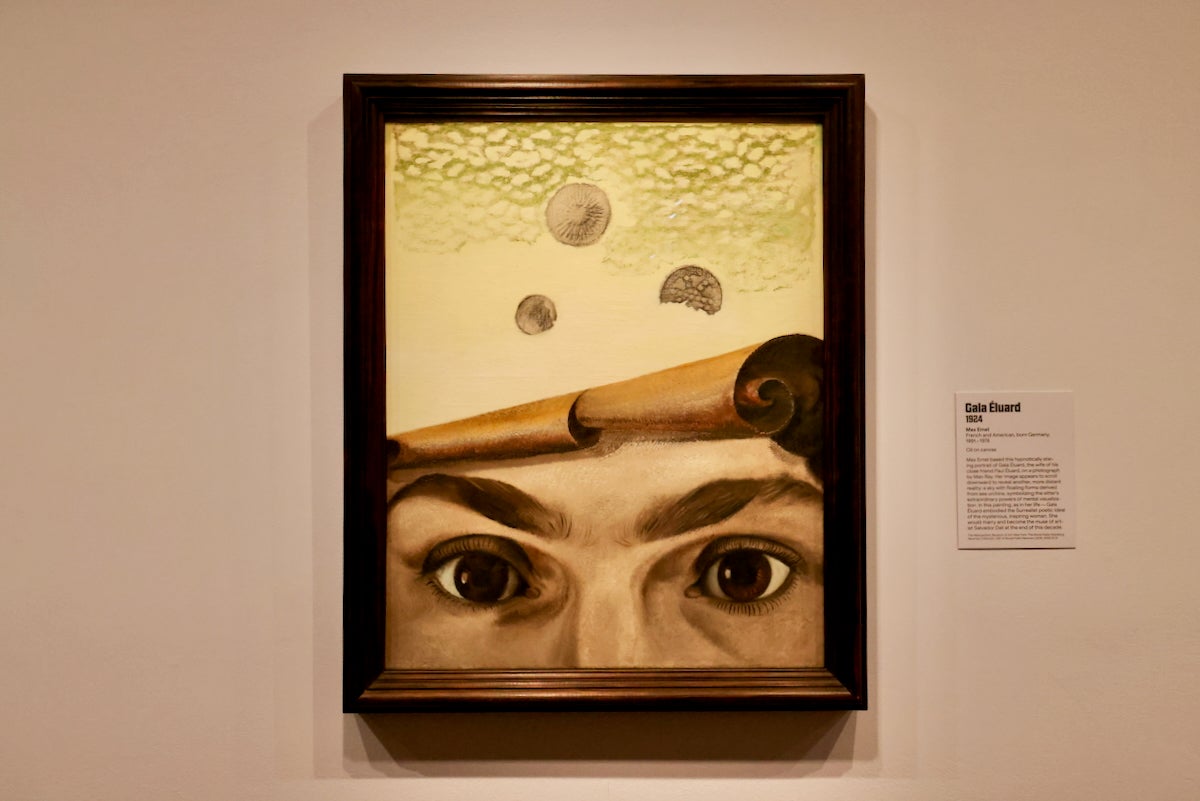

“Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100” is an overview of the first 25 years of the art movement that started in Paris in 1924 and was almost immediately tested by the rise of European authoritarianism, before it was exiled into North and South America.

Surrealism came out of a previous movement called dadaism and was influenced by Sigmund Freud’s studies into the subconscious, but its birth can be conspicuously pinpointed to a specific date, Oct. 15, 1924. That is when poet André Breton published “The Surrealist Manifesto,” which embraced irrationality and dreams to unlock creativity.

“There exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions,” Breton wrote.

Curator Matthew Affron said Breton did not invent surrealism. Rather, he was the first to articulate it as a revolutionary act.

“Breton codified a philosophy of life, a way of living, a way of being,” Affron said. “It’s about using all sorts of methods rooted in the history of poetry, in the history of art, in the influence from Freud’s psychoanalysis, in radical politics – all coming together in the manifesto as a statement about changing the way you see the world.”

“What surrealism wanted, fundamentally, was a revolution in consciousness,” he said.

At its core, “Dreamworld” is a traveling exhibition that has been to Belgium, France, Spain and Germany. Its fifth and final stop is in Philadelphia.

The show is different in each city where it lands. Every museum has curated it individually with different works. About 35% of the Philadelphia Art Museum’s iteration of the exhibition comes from its own collection.

Affron said the PAM’s collection is particularly strong in surrealist art, thanks in part to major donations in the 1950s of avant-garde works from donors Walter and Louise Arensberg and Albert Gallatin.

“This exhibition is an opportunity to combine works that people who know our museum well will recognize, with tremendous loans from institutions and private lenders in Europe and North and South America,” he said, “telling the story of surrealism in a new way.”

What is surrealism?

There are about 180 works on view in “Dreamworld” representing the scope of surrealism as more than melting clocks or a green apple wearing a bowler hat. For advocates like Breton, surrealism is not a style or technique but an inquiry into subconsciousness that requires the artist to fool their own brain to arrive at mental states akin to psychosis.

The exhibition includes works by André Masson who used automatic drawing, making marks with no clear intention but to see how they work together. The Spanish artist Joan Miró made sketches “disconnected from reality” as the basis for abstract paintings such as “The Hermitage” (1924).

There is a cluster of folded paper exquisite corpses, a communal drawing technique of breaking down a figure into several parts, each artist drawing a section without the others seeing. The results were usually discordant, monstrous chimeras that no single artist could have intentionally envisioned.

“This idea of finding a technique which evades your conscious control is really the central part here,” Affron said. “It’s what makes the exquisite corpse such a famous and emblematic type of surrealist work.”

Surrealism faces the real world

The surrealists’ techniques of and philosophies were fairly well developed by the 1930s when world events challenged their sensibilities. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War followed almost immediately by World War II marked a rise of European authoritarianism, the antithesis of surrealism’s socialist roots.

The gleeful monsters of irrationality that the artist nursed in the 1920s were unleashed to represent the brutality of war.

Affron points to Max Ernst’s “The Fireside Angel” (1937) as one of the most important pictures in the exhibition. It depicts a multicolored, hybrid animal of indeterminate species that appears to be engaged in an ecstatic, terrifying dance.

“A monster exemplifies the idea in surrealism of surprising juxtaposition as an incredibly strong creative tool,” he said. “Monsters return in the 1930s when surrealist artists are looking for a way to react to the terrifying political and social developments of the time.”

Spread the Manifesto to the Americas

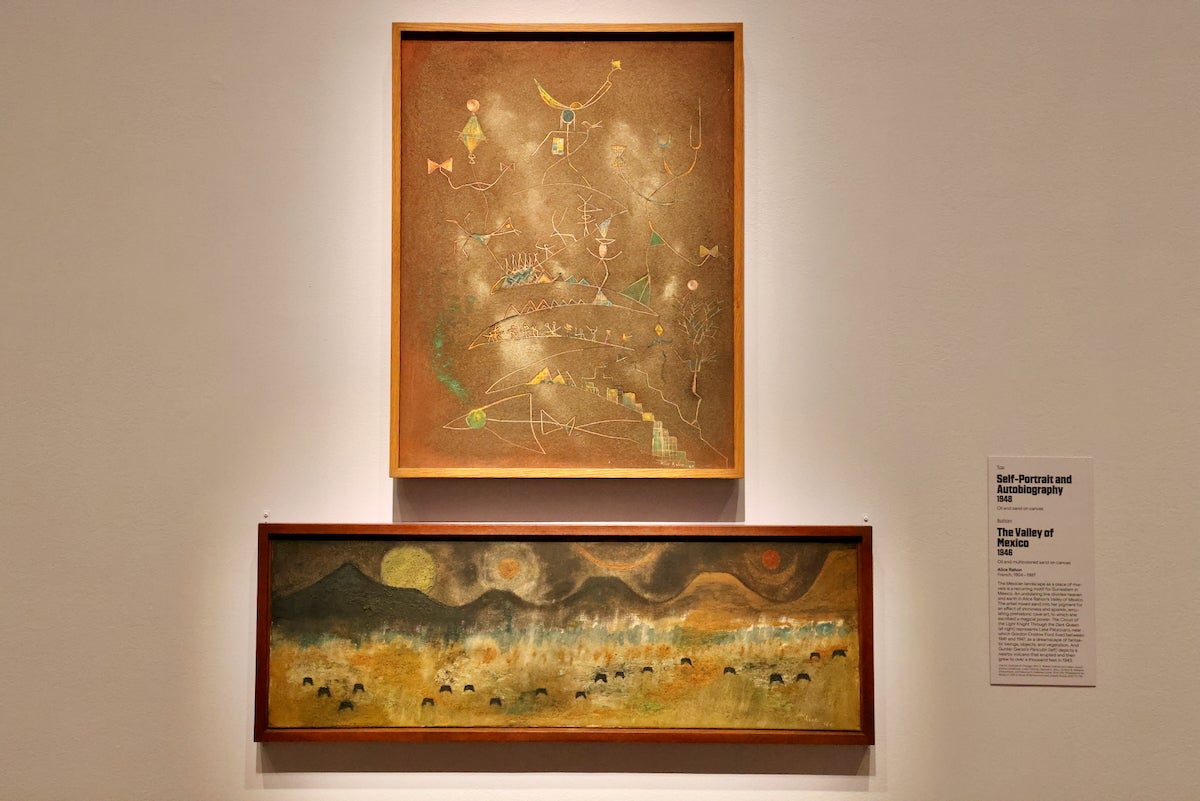

During World War II, many surrealist artists from France and Spain fled Europe and found safe haven in Mexico and the United States. There, surrealist approaches to art spread among artists who did not consider themselves surrealists.

Affron included a small painting by Frida Kahlo, “My Grandparents, My Parents, and I” (1936), which shows the artist as a young girl tethered to her ancestors by a red ribbon. While Kahlo did not subscribe to Breton’s manifesto, he considered her work as authentic expressions of surreality, once quipping that “Mexico is the surrealist country in the world.”

“Dreamworld” includes several early works by American artists who later became the basis of another art movement, abstract expressionism, such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottleib and Arshile Gorky.

Pollock’s “Male and Female” (1942) was made shortly after the artist underwent Jungian psychoanalysis. The symbolism in the painting likely comes from Jungian dream studies, and the painting appears to have marks derived from automatic drawing.

“There is no such thing as a surrealist style,” Affron said. “Any method counted as a good method if it could accomplish the underlying aim of breaking down that barrier between the conscious and calculating part of the mind, and the unruly, unconscious spontaneous, maybe scarier part.”

“Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100” will be on view at the Philadelphia Art Museum from Nov. 8, 2025 to Feb. 16, 2026.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.