Philly Alzheimer’s disease researchers call a new diagnostic blood test promising, but advise caution

The blood test measures two subtypes of tau and amyloid proteins, which can indicate the presence of amyloid plaque in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Listen 1:14

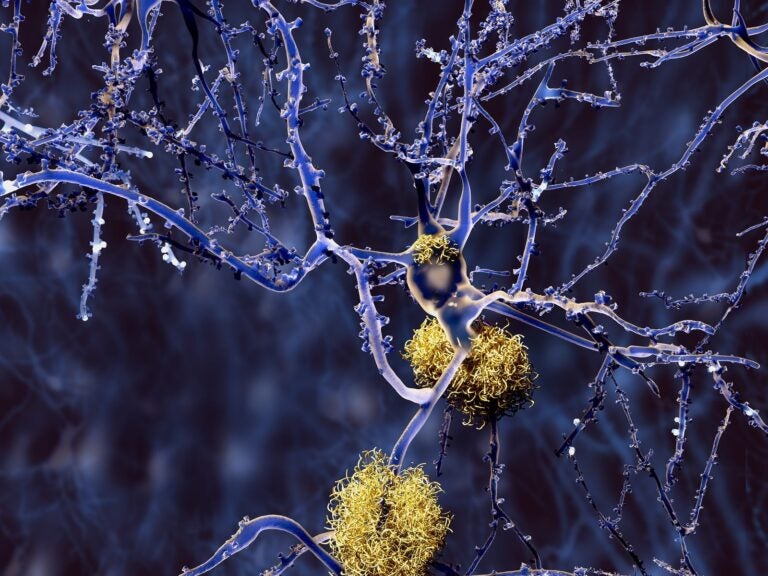

Amyloid plaque, a feature of Alzheimer's disease, accumulates outside neurons. A new blood test, Lumipulse, measures two subtypes of tau and amyloid proteins, of which certain levels can predict the presence of amyloid plaque in the brain. (Bigstock/animaxx3d)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Health providers hope a new blood test for Alzheimer’s disease will lead to quicker and earlier diagnoses of the progressive form of dementia, which affects nearly half a million people in the tri-state area.

The Lumipulse blood test became the first “in vitro diagnostic device” to be endorsed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which cleared it earlier this month as a new tool in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.

Federal and local health experts hope that it can make diagnostic care more accessible at a time when the overall population is aging and more people are experiencing signs of cognitive decline.

“I see this as being something that could be really good at a very early point in time to have a better diagnosis,” said Brian Balin, an Alzheimer’s researcher at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. “Then, planning from there — how are you going to now start therapeutics?”

More than 480,000 people aged 65 and older in Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania are living with Alzheimer’s disease, according to federal estimates.

There is no cure, but an early diagnosis can give patients the opportunity to start treatments and medications that can help manage symptoms like agitation and depression, experts say.

Newer treatments, including drugs like Leqembi and Kisunla, aim to slow disease progression by clearing away amyloid plaque in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, but these medications are still being studied in terms of their effectiveness, and come with side effects and high price tags.

The new blood test measures two subtypes of tau and amyloid proteins. Certain levels of these proteins in the blood “can reliably predict” the presence of amyloid plaque in the brain, according to clinical trial results.

Brain imaging tests like PET scans, which use radiation, can also identify amyloid plaque, but FDA officials said they hope the blood test could serve as a less invasive, less costly option.

Balin, director of the Center for Chronic Disorders of Aging at PCOM, said providers should be cautious when relying on the blood test, because these proteins can also appear elevated in blood for reasons other than Alzheimer’s, including brain injuries and Parkinson’s disease.

For example, he said, someone may go see their primary care physician with concerns of memory issues.

“They [doctors] say, ‘Ok, well let’s get a blood test’ and they’re only testing for the different levels of amyloid and tau,” Balin said. “That comes back from the lab and now they’re going, ‘Well, we’ve confirmed that you have Alzheimer’s disease,’ without necessarily ruling out that there could be something else there.”

This could lead to incorrect diagnoses and unnecessary panic for patients, Balin said.

“What should happen here is that a primary care physician using this information should then require advanced testing,” he said. “Go to a neurologist, neuropsychology or geriatricians who would then give you more advanced testing to get better confirmatory evidence that it is most likely Alzheimer’s disease.”

Advanced testing can include a mental status exam; neuropsychological assessments; metabolic tests to rule out other conditions and factors that can cause cognitive issues; MRI, CT and PET scans; and thorough medical history documentation.

Balin said primary care physicians might use the blood test and conduct some of the above exams to provide an Alzheimer’s diagnosis for people in rural areas, where there are fewer neurology and gerontology specialists.

The FDA said the new test is not meant to be used as a broad screening tool for all older adults, or as the only test to make a diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease. Additional testing should be done to determine treatment options.

Show your support for local public media

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.