People’s Light Theater gets a crash course in West Chester’s Black history

The cast and crew at People’s Light Theater were given a crash course in West Chester’s Black history for their premiere of “Bayard Rustin Inside Ashland.”

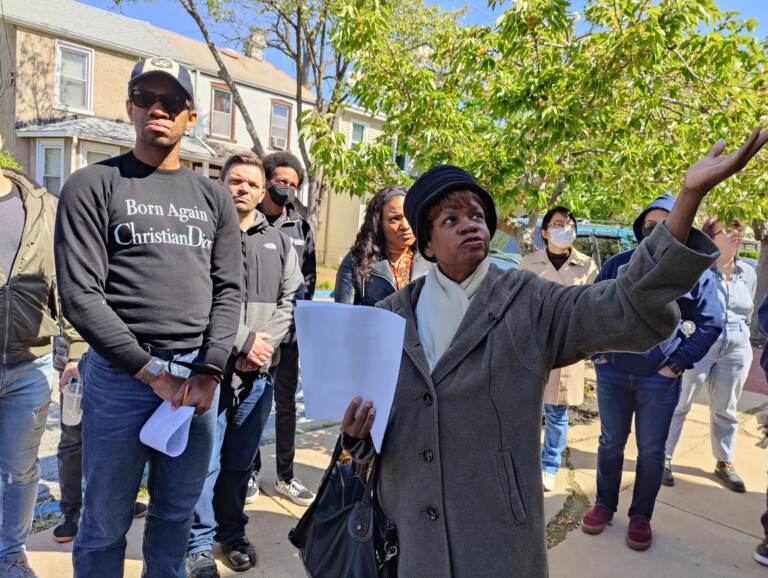

Penny Washington shows actor Reggie White and the rest of the cast and crew of the new play 'Bayard Rustin Inside Ashland' the historic A.M.E. church in West Chester where Rustin grew up. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The story of civil rights activist Bayard Rustin almost always starts with his crowning achievement: organizing the 1963 March of Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech.

Rustin’s place in the story of the Civil Rights Movement had often been obscured by history because he was an openly gay man, a fact that was troubling for the movement at the time.

But a new play premiering at People’s Light in Malvern, Pa., “Bayard Rustin Inside Ashland” starts somewhere else: an A.M.E. church in West Chester, on East Miner Street.

“This church is significant to our understanding of Rustin because his grandparents were married [here] by Reverend John C. Brock,” said Penny Washington, aka Miss Penny, a local historian whose family roots in West Chester go back four generations. “Bayard Rustin’s grandfather, Janifer Rustin, was a respected, trusted member of this African Methodist Episcopal denomination.”

Washington led the cast and crew from People’s Light on a Black history walking tour of West Chester, where Rustin grew up a century ago. She wanted the theater company to have a better understanding of what shaped Rustin’s intellect and activism at an early age.

She also wanted the production crew to get the details right.

“I would like for the production team to note the Romanesque arched windows,” Washington said, pointing to the stained glass in the brick facade. “This Romanesque arched window is a unique feature among the Black churches in West Chester, because other churches have a Gothic arch.”

“Bayard Rustin Inside Ashland” opens this week, running until June 12.

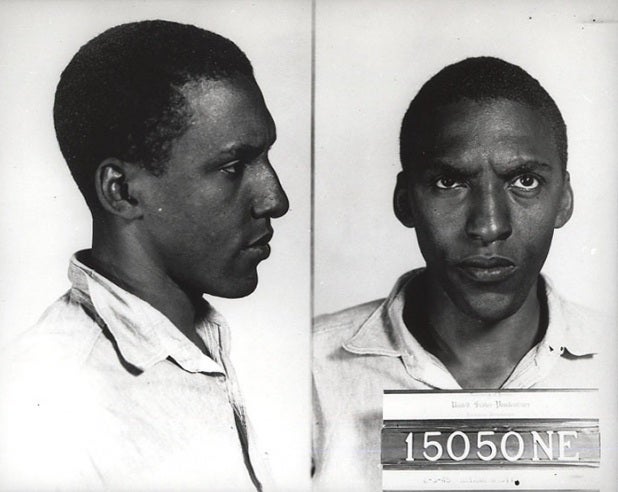

The action of the play begins inside the A.M.E. Church, quickly jumping decades later to Ashland prison, in Kentucky, where Rustin was held for dodging the WWII draft.

Because he identified as a Quaker, the religion of his grandmother, Rustin would have been able to legally avoid serving as a soldier, as a conscientious objector.

However, he refused to invoke that religious exception, and instead was determined to directly oppose the war by putting himself through legal consequences, including imprisonment. It was not the first time he would be jailed, nor would it be the last.

While imprisoned, he continued his activism by working to integrate the institution, requesting he be allowed to teach a cultural history class to other inmates.

“He believes unless so placed in the Education Department it would be a clear indication the institute desires to follow a short-sided policy of racial segregation,” read the warden’s report at the time. “It is believed this inmate will continue to bring up racial problems in the institution.”

The fact that this play about Rustin, who identified as a Quaker, would open in an African Methodist Episcopal church is significant. Rustin may have followed his grandmother’s lead into Quakerism, but Washington posits it was the A.M.E. church that really shaped his activism.

She pointed out that Rustin’s grandmother, Julia Davis, was a Quaker because her parents worked for a white Quaker family and adopted their religion. Once she married Janifer Rustin she became part of his Black A.M.E. congregation

“That act allowed Julia Davis Rustin to have access to the Black, educated middle class of the community,” said Washington. “Julia Davis had access to the Black leadership by her being a member of this church, and her having access to that is going to allow her grandson to see that a Black leadership class existed.”

Washington took the crew to the house of one of Rustin’s teachers, Mariah Brock, who was a stickler for diction. Washington believes Rustin’s distinctive way of speaking, which often had a formal quality akin to a British upper-class mannerism, was due to Brock.

The actor playing Rustin, Reggie White, took the opportunity to walk next to Washington to question her about meeting Rustin in person. Rustin died at age 75 in 1987.

“People comment on his speaking voice, but what I remember most when he spoke to you – I had the feeling that I had been truly seen,” Washington said.

“What was it about the way that he would speak with you, that would make you feel that?” White asked.

“Because he would look you right in the eye,” she said.

By the time of this walking tour, about three weeks before “Ashland” premieres, the script had already been written by Steve H. Broadnax III, and his direction of the play is well under way. He said taking everyone involved in the play away from the rehearsal studio and into the street with Washington is invaluable.

“Today, we’ll go from this tour to rehearsal and I know the things they’re learning now will merge into the script,” said Broadnax. “Like, today we’ve been learning about Rustin’s teacher and his speech. I mean, you can’t find that in a book. You only find it from Miss Penny.”

This is not the first time Washington has schooled a cast and crew from People’s Light. A 2019 play “Mud Row,” by Detroit playwright Dominique Morisseau, was based on the history of West Chester’s East end where historically, Black residents have been working together for more than a century to maintain their neighborhood and, more recently, attempted to stave off its gentrification.

The artistic director of People’s Light, Zak Berkman, said the company has been building partnerships with neighborhood groups to develop new plays based on people and events in the community.

“Most plays are developed in their own vacuum. They exist in a rehearsal room,” he said. “What a chance for people to really feel the connectivity of what they are doing with the environment around them, with the neighborhoods and communities around them. That invests the play with a whole different sense of humanity. I think four hours in West Chester is worth four weeks in a rehearsal room.”

Washington led the People’s Light cast and crew to the 200 block of East Market Street, which had been a mostly Black business corridor in Rustin’s day. He and his activist colleagues – which he called “angelic troublemakers” – would gather at the Royal Palace Luncheonette to discuss their next moves.

One of those moves was to protest the segregation of the nearby Warner Theater, where Black patrons were forced to sit in the balcony. That action would lead to Rustin’s first arrest.

The group also gathered at West Chester’s municipal building on East Gay Street, the former site of the Gay Street School, a segregated Black school where Rustin was educated. Washington made sure everybody clearly heard the names of his teachers: Mariah Brock, Sarah Maxfield, Katherine Walton, Warren Burton, Joseph Fugett, and his wife Hazel Fugett.

“Black teachers prepared him with knowledge and wisdom. There’s a difference between knowledge and wisdom: knowledge is fact, but wisdom would tell you what to do with it,” she said, as the crew from People’s Light sent up a cheer. “It was the Black teachers that gave him that understanding.”

Washington has a photo of Rustin as a very young boy, standing in front of the Gay Street School with his classmates and teachers. For Washington, it’s a personal family photo.

“I have family members in that picture, but they have all since passed,” she said. “That picture shows Bayard Rustin embraced, encased, ensconced within Black love and community.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.