Penn Museum unveils a new look at the ancient Mediterranean world

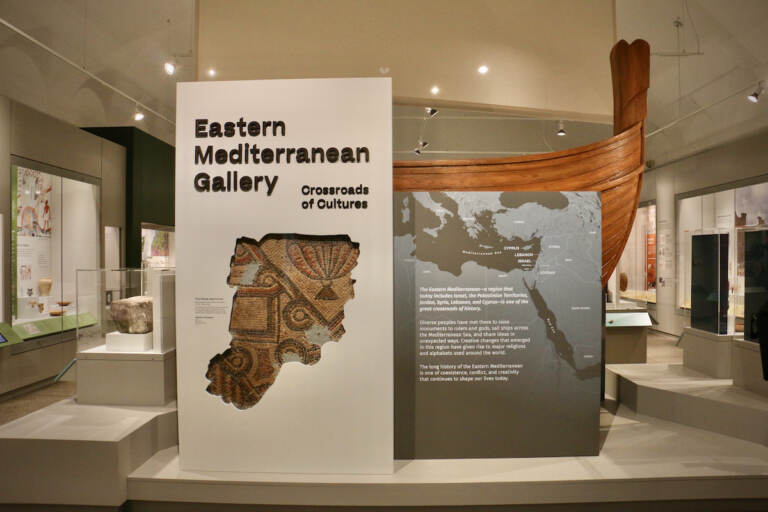

The new Eastern Mediterranean gallery at Penn Museum updates the ancient “crucible” that gave rise to the pillars of our modern world.

Penn Museum's revamped Eastern Mediterranean Gallery contains nearly 400 artifacts and new interactive features. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

It all starts with the A-B-C’s.

Some of the artifacts featured in the freshly renovated and reimagined Eastern Mediterranean Gallery at the Penn Museum of Archeology and Anthropology include small ceramic objects from an Egyptian mine circa 1200 BCE, made by Canaanite miners to honor the goddess Hathor.

The miners wrote dedications to the deity, spelling out words with letters rather than using hieroglyph symbols. Those laborers may have developed the first alphabet.

“There is a big debate about who actually invented the alphabet,” said co-curator Virginia Herrmann. “There’s some people who think it would have been humble miners who were looking to make their dedications to the goddess. Other people think, no, they must have been scribes — they’re coming out of an elite stratum of scribal culture. So we don’t have a smoking gun for that yet.”

The new, permanent exhibition has nearly 400 objects ranging from about 2000 BCE to the more recent Ottoman Empire of the 1800s. They describe the general Eastern Mediterranean region, including what is now Egypt, Turkey, Isreal, Syria, and Iran, as a vital cross-cultural terrain that gave rise to pillars of modern civilization, including the alphabet and monotheistic religions like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

“The Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East are very much part of our contemporary worldview but in a very limited way, identified with conflict and with little nuance or depth,” said Museum Director Christopher Woods. “This was an incredibly important crossroads in antiquity, a crucible for innovation and new ideas.”

Woods said the exhibition also represents a crossroads of the museum, itself. The Eastern Mediterranean gallery ties together several areas of research into a single room.

“It includes material from our Mediterranean section, from our Egyptian section, from the Babylonian section, from the Asian section,” Woods said. “It really is a type of fulcrum for the entire museum because it, by its very nature, pulls together all of this material.”

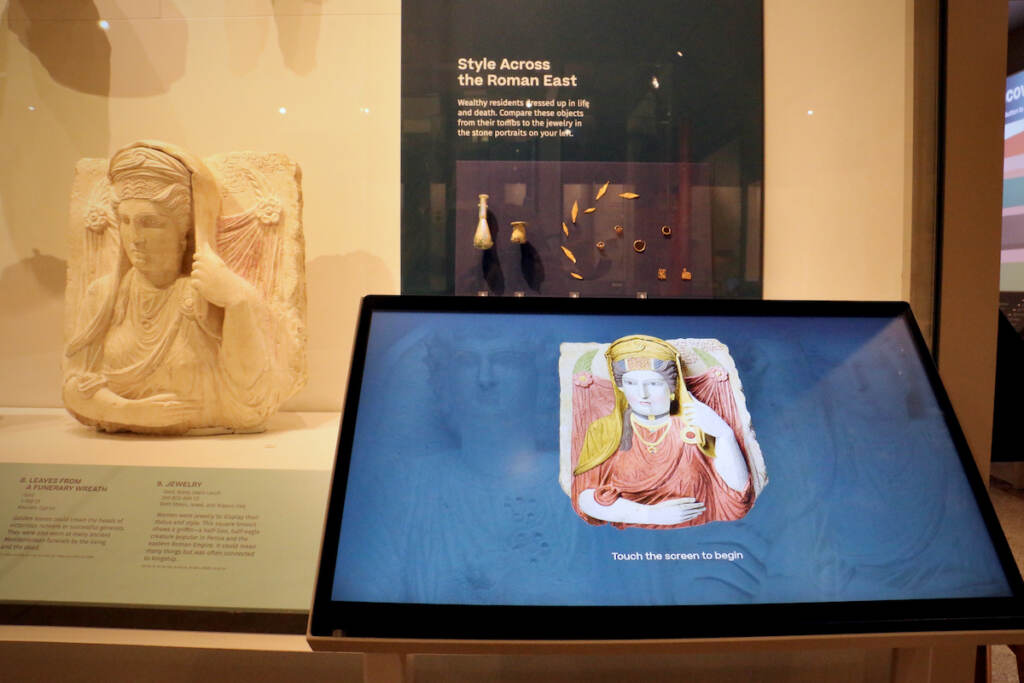

The new exhibition is brighter than its predecessor, with new lighting and some of the windows that had been built over that are now revealed, bringing in more natural light.

The historic building on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania is undergoing a major interior transformation that will take years to complete. The unveiling of the Eastern Mediterranean gallery represents a mid-point of the multi-phase project.

The exhibition presents that region of the world as a mashup of intersecting cultures that were constantly overlapping. A portion of a boat, loosely based on a 1300 BCE trading ship discovered off the coast of Turkey in the 1980s, has been reconstructed in the gallery. Its hull is filled with artifacts found far and wide across the Eastern Mediterranean region that likely would have been traded by water.

“What we’re really talking about here is the development of much larger-scale shipping, with a ship that measures as much as 50 feet in length, able to travel over much vaster distances in the Eastern Mediterranean on a more regular basis,” said co-curator Joanna Smith. “So it’s really a vast increase economically.”

The exhibition also spends time explaining how these objects came to be at the Penn Museum.

Most ancient objects were acquired through the University of Pennsylvania’s own archeological excavations, beginning in 1889, often in partnership with the British Museum. Many digging projects would have been done during periods of colonialism.

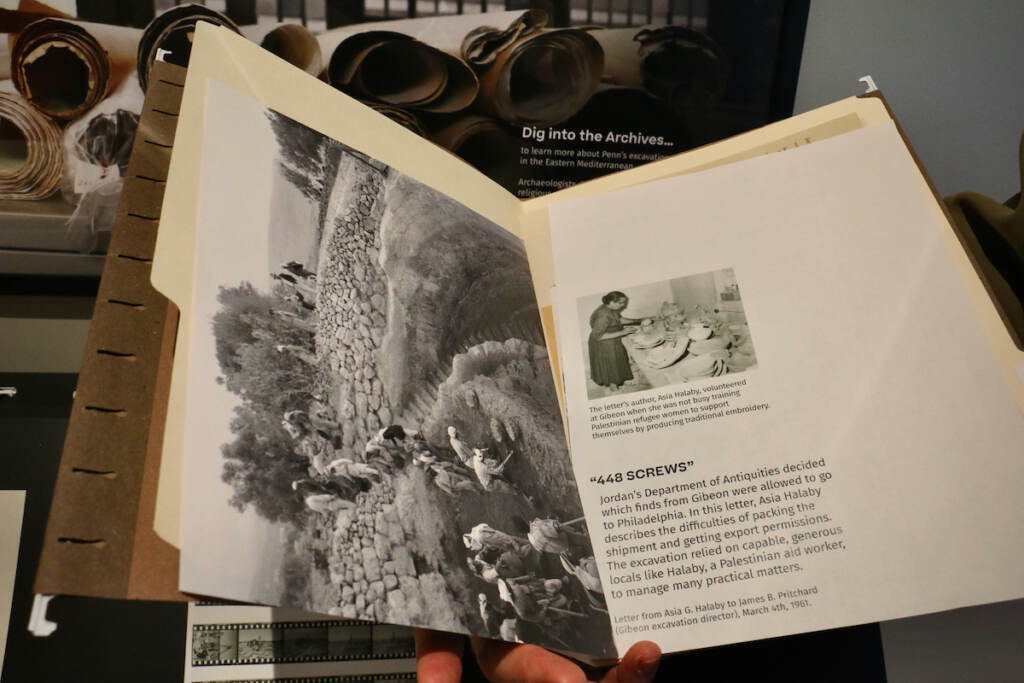

A section of the gallery includes file folders containing reproductions of documents and photos from three areas of excavation in the Eastern Mediterranean: Gibeon and Beth Shean in what is now Israel, and Kourion in Greece.

The British military could sometimes block archaeological work. Inside the manila folders is a reproduction of a 1919 telegram from a British administrator in Jerusalem, described as “occupied enemy territory.” It’s addressed to Penn archaeologist Clarence Stanley Fisher explaining that he could not excavate in Beth Shean until “the future Government of the country is defined.”

The folders include spicy details of the business of running an excavation. In 1956 archeologist Richard Pritchard frantically telegrammed the Penn Museum when the local bank in Jerusalem had not received a line of credit that would pay for the Gibeon dig: “Kindly raise hell with Philadelphia bank.”

The papers also reveal who did the actual work at dig sites. Lead archeologists would not only hire laborers locally, but key professions like illustrators, registrars, and surveyors.

Herrmann points to one notable Palestinian woman of Russian background who assisted Pritchard at Gibeon. Asia Halaby managed the packing of antiquities and shipping them to Philadelphia to the satisfaction of the Jerusalem Antiquities Department.

In her 1961 letter on view, Halaby explained that she personally nailed together wooden crates and screwed protective iron corners on them. It took 448 screws to secure the crates. Halaby asked Pritchard if he had anyone in Philadelphia to help him unscrew them all.

The letter was typed on letterhead from the Arab Refugee Handworks Centre in Jerusalem, an organization Halaby founded.

“Archaeology was just one part of her story,” said Herrmann. “She was an officer in the Arab Legion, one of the only women to hold that role. She ran a refugee handworks center where she trained Palestinian woman to make traditional embroidery to help support themselves. She was a remarkable person.”

The Eastern Mediterranean gallery opens to the public on Saturday November 19, with a weekend of activities planned.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.