In face of Pa. teacher shortage, staffing services struggle to meet demand for substitutes

Listen 4:50

Professional development specialist Nora Connell hands out materials during a class for prospective substitute teachers at Delaware County Intermediate Unit. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

On average before they graduate high school, American kids sit in class without their regular teacher for what adds up to most of a school year.

But what happens if there aren’t enough substitutes?

Hundreds of school districts in Pennsylvania have turned to private staffing companies amidst a substitute teacher drought, but outsourcing alone hasn’t fixed a broken pipeline.

‘Everyone has been struggling’

Let’s start big picture.

Pennsylvania is in the midst of an extreme teacher shortage.

In 2013, 16,631 people graduated from teacher-training programs. In 2015, that number had dropped to 6,125, according to data from the state’s Department of Education.

Pennsylvania requires substitute teachers to have all of the same training and degrees as classroom teachers, so fewer trained teachers means fewer subs.

“In the past, the pool has relied on teacher program graduates from across the state to come in an substitute and sort of get their feet wet into the role of serving as a teacher,” said Jim Buckheit, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators.

The teacher shortage, which can also be felt nationally, “is really ratcheting up the challenges of filling day-to-day substitute teachers,” said Buckheit.

Those challenges are felt schoolwide. When no substitute can be found, a principal has to scrap that day’s plans to fill in, or another teacher may lead two classes at once in the cafeteria or gym.

Pushed by low numbers of subs and mounting benefits costs, school districts have turned to private companies to staff and manage substitute teacher positions.

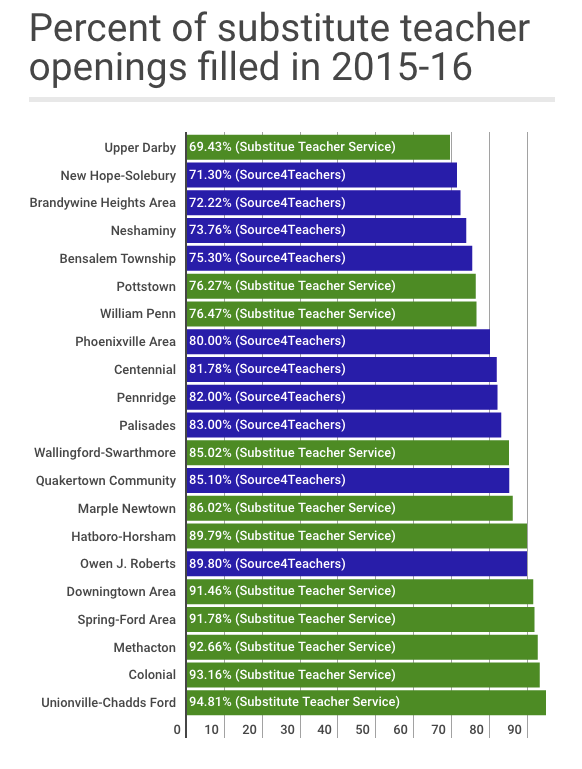

NewsWorks looked at a sample of 21 districts in Southeastern Pennsylvania that use one of the two biggest staffing agencies, Source4Teachers and the Substitute Teacher Service. Combined, the two companies work with 175 of the more than 500 districts across the state.

Last year, only about a quarter of the districts surveyed were able to consistently place substitute teachers in classrooms 90 percent of the time or better, considered a “good” rate.

A handful of these districts also shared historical data, and those that did showed a real mixed bag. Some got a little better, some worse and some stayed about the same. None showed dramatic improvement.

Quakertown Area Schools saw fill rates drop from around 95 percent of absences covered by a substitute teacher in 2012-2013 to an average of 85 percent over the next three years. The district’s contract with Source4Teachers began in December 2013.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of districts and human resource directors, and we really haven’t seen as strong correlation, whether it’s in-house or third party,” said Zach Schoch, director of human resources for Quakertown Area Schools. “Everyone has been struggling,” he said.

Owen Murphy, spokesman for Source4Teachers, said he couldn’t speak to individual contracts, but “we have a goal of filling every classroom, every day.”

Fill rates also tend to be a proxy for how desirable it is to work in a school system, so lower-income districts with fewer resources that have a harder time attracting classroom teachers also struggle more finding substitutes.

Most districts — even ones where private companies have struggled to find enough substitutes — stick with outsourcing, citing cost savings on pensions and health care.

“Two of the biggest reasons were the Affordable Care Act and the PSERS contribution rate … between those two things, the cost would have been exorbitant,” said Drew Bishop, business administrator at Palisades School Districts.

He said the school district officials have not discussed changing providers, in spite of Source4Teachers not meeting its fill rate target of 90 percent.

In addition to cost savings, many school administrators said private companies have other advantages. The companies can spread subs out over more than one district, and have dedicated marketing and recruitment positions, as well as hire retired teachers without jeopardizing their pensions.

In one high profile case, the Philadelphia School District did sever its contract with Source4Teachers, after fill rates plummeted. The district has since signed on with another provider, Kelly Educational Services.

A temporary solution

School districts and private companies can’t push more people into the teaching profession. Instead, they’re expanding who can enter it, temporarily, by leaning on emergency certification, or “guest teacher,” programs.

Emergency certification is just what it sounds like, a sped-up training program to get temporary subs certified when more qualified candidates aren’t available. Anyone with a bachelor’s degree can apply and work for one year before having to reapply.

“They can barrel through in a six and a half to seven hour time period and get it all done at once, or do it at their leisure,” said JR Godwin, vice president of business affairs for the Substitute Teacher Service, of his company’s online certification.

Substitute teacher companies, as well as school districts, have been promoting the option with renewed fervor in recent years, certifying hundreds of teachers who take trainings and pass all necessary background checks.

After dropping off in 2013, the number of emergency certifications handed out annually by the the state of Pennsylvania shot up in 2015, to more than 10,500.

A measure introduced by state Sen. Lloyd Smucker, R-Lancaster, proposing anyone with 60 credits in a teacher college could work as temporary substitute teachers, also went into effect this month.

While no one says having substitutes with a lower level of training is better, giving people a chance to sample the profession before might help solve the root problem — less interest in teaching.

On a steamy weekday morning, 13 future substitute teachers spread out around a small classroom at the Delaware County Intermediate Unit which oversees all districts in that county. In two days, they would complete a training that runs the gamut from child development to classroom management.

“Children are my heart,” said Pam Reid. “I have three of my own and I love them all and that’s how I ended up here today.”

Reid used to teach at a private school. That was before having kids and later becoming a social worker.

“They’re going to let me go into classrooms, meet children and determine if this is how I want to finish my career,” said Reid.

Of course, if she graduates to teaching full time, that’s one less person in the pool of substitute teachers.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.