Oscar Hammerstein’s farmhouse in Doylestown will become a museum

The ink is dry on a deal to buy the musical theater giant’s property in Doylestown, Pa., to turn it into a museum and education center.

Listen 3:09

Highland Farm in Doylestown, once home to Oscar Hammerstein II and his family, will become a museum and theater education center, honoring Hammerstein's work as a lyricist, librettist, mentor, and humanitarian. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

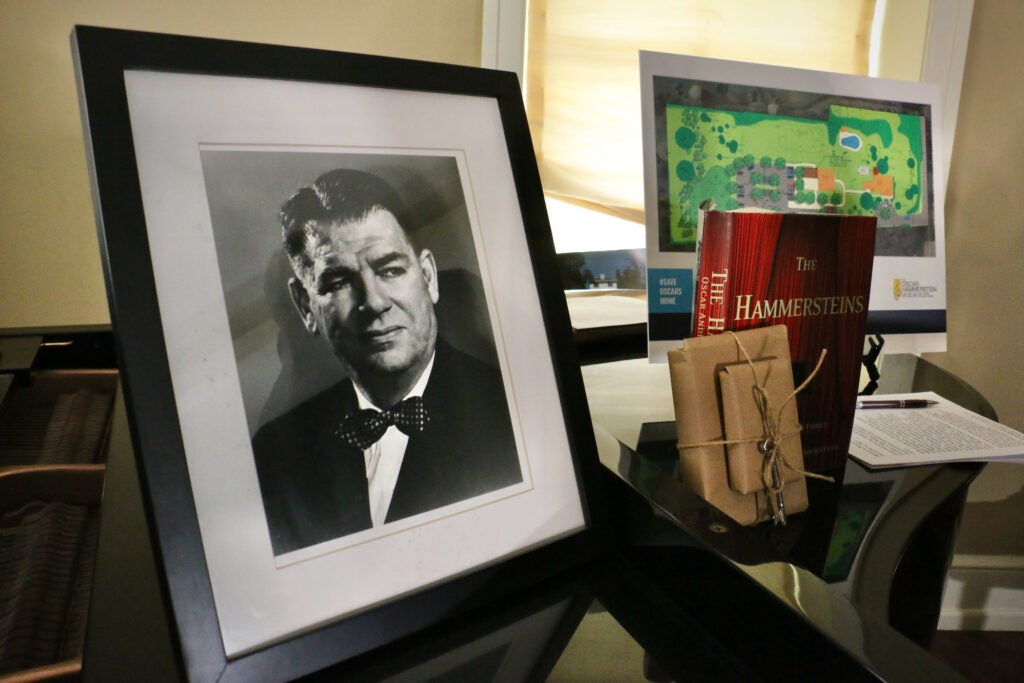

Greg Roth, board president of the Oscar Hammerstein Museum and Theater Education Center, has a knack for peppering his statements with lyrics from Hammerstein songs.

“You got to have a dream. If you don’t have a dream, how you gonna have a dream come true?” he told a crowd gathered at Highland Farm, in Doylestown, Pa., last week, in a nod to “South Pacific.” “Our dream is coming true with the purchase today.”

Earlier that morning the OHMTEC closed escrow on the farmhouse once owned by the legendary lyricist, finalizing a $2-million real estate deal to turn the property into a museum. It was a goal 15 years in the making.

“How did we get here?” Roth teased the crowd with a hint of “The Sound of Music.” “Let’s start at the very beginning. It’s a very good place to start.”

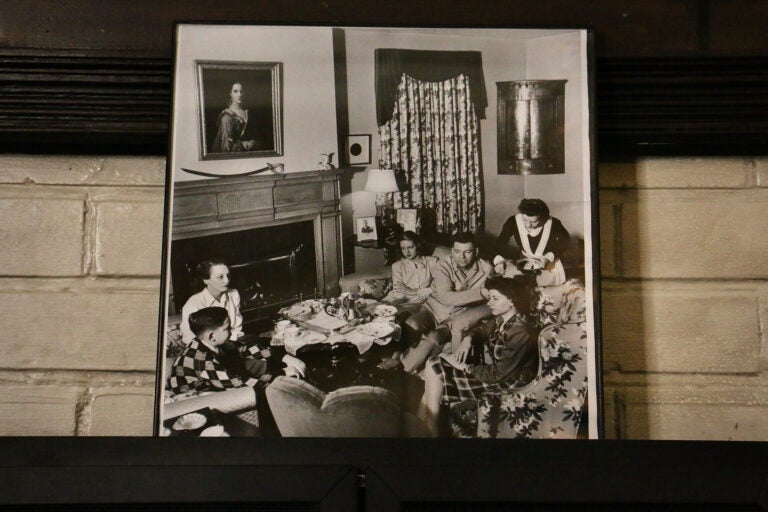

Highland Farm and its 1840 farmhouse was bought by Oscar Hammerstein and his wife Dorothy in 1940. The couple split their time between New York City and Doylestown until Hammerstein died in the farmhouse in 1960. The last song he ever wrote was “Edelweiss,” a lament for Captain von Trapp’s Austria in “The Sound of Music,” composed in one of the upstairs rooms.

During his 20-year residence in Doylestown, Hammerstein launched a relationship with his songwriting partner Richard Rodgers, and wrote the foundation of modern American musical theater, including “The King and I,” “Oklahoma,” “Carousel,” “South Pacific,” and “The Sound of Music.”

The house was also frequented by the future composer Stephen Sondheim, a friend of Hammerstein’s son, who learned songwriting at the feet of the master. Sondheim regarded Hammerstein as his most important mentor.

The house has operated as a bed and breakfast for decades, with rooms themed to Rodgers and Hammerstein shows. It hosted its final guest last summer. The now-former owner, Christine Cole, has supported the effort to turn it into a museum.

“Part of me is gonna miss it, and then part of me is relieved to not have this responsibility,” Cole said. “It was a big responsibility over the years.”

Not to be outdone lyrically, after signing the paperwork Cole ceremoniously presented the house keys to Roth as a stack of brown paper packages tied up with strings.

Hammerstein’s grandson, Will Hammerstein, originally proposed a museum and 400-seat theater on the property in 2015, a plan that was struck down by the Doylestown zoning board. So as a founding board member of the OHMTEC, he spent years brainstorming ideas on how to pair a house museum with a revenue-generating operation.

“A yoga studio, a farmer’s market,” Will said. “None of these ideas would save the barn. It took too much money.”

Will decided to leverage the property’s singular character as the site where the most memorable songs of American musical theater canon were conceived.

“When you hear these songs in the house where they were written, it hits different,” he said.

The Bucks County landscape may have inspired lines in Hammerstein’s songs. Roth points to a lyric in “Oh What a Beautiful Morning”: “The corn is as high as an elephant’s eye.” Hammerstein liked to walk while he worked, so he would pace his second-story wrap-around balcony overlooking cornfields (now the Route 202 bypass freeway).

Elephants once roamed the property. A previous owner ran a small circus and built a barn tall enough to accommodate elephants. A small pond next to the barn was used to water them. It is still called Elephant Pond.

The house needs some repairs. That second-story balcony cannot be safely accessed, and the elephant barn is in danger of imminent collapse. The OHMTEC is raising $3 million to fix the house and raze the barn, which will be rebuilt as a musical theater education center.

Will Hammerstein, who is no longer formally involved with the museum, hopes the endeavor will not just teach people to be better songwriters, but to be better people.

“He was a great man. He wasn’t just a great lyricist,” he said. “He gave seven hours of every day to the theater, and one hour to society.”

Will listed some of causes for which Hammerstein was a champion, including the racial integration of baseball, the creation of the United Nations, the formation of an anti-Nazi league two years before Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, and the case of Recy Taylor, a Black woman in Alabama who was violently assaulted by six white men in 1944.

Hammerstein’s anti-racist views came out in his songs, particularly “Carefully Taught” from South Pacific.

“If you listen to the lyrics of his songs, he’s not just a guy who sat up in his office and dreamed of being a better man,” Will said. “He actually did it.”

The Oscar Hammerstein Museum had already started operating inside the house before it legally owned it. Cole, the farmhouse’s former owner, allowed the museum to give docent tours while the real estate deal was in escrow. The museum also held a music festival at the property in October, which it expects to become an annual event.

But the house is still set up as a bed and breakfast: None of the original furnishings used by Hammerstein remain. After his death in 1960, his wife Dorothy sold the house and everything inside of it. Since then the furnishings have scattered.

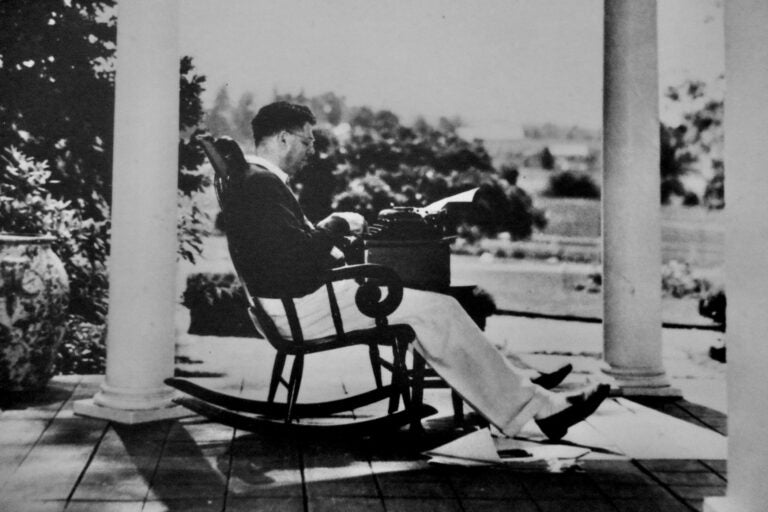

Roth said the OHMTEC is on the hunt for some of that original furniture. It has already acquired a rocking chair Hammerstein was known to sit in while writing, and his bar cart is expected shortly.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.