Operation Hug the Block marches on: Late-night Peace Patrols, community safety, and a City Council promise

On Monday, 12 City Council members voiced their support for the project, following an attempt by an unknown person to scare away volunteers on patrol in Kensington.

Emmanuel Bussie, right, discusses the plan for the next hour of patrol. (Sam Searles/WHYY)

It’s 10:35 p.m., Thursday, September 21, 2023.

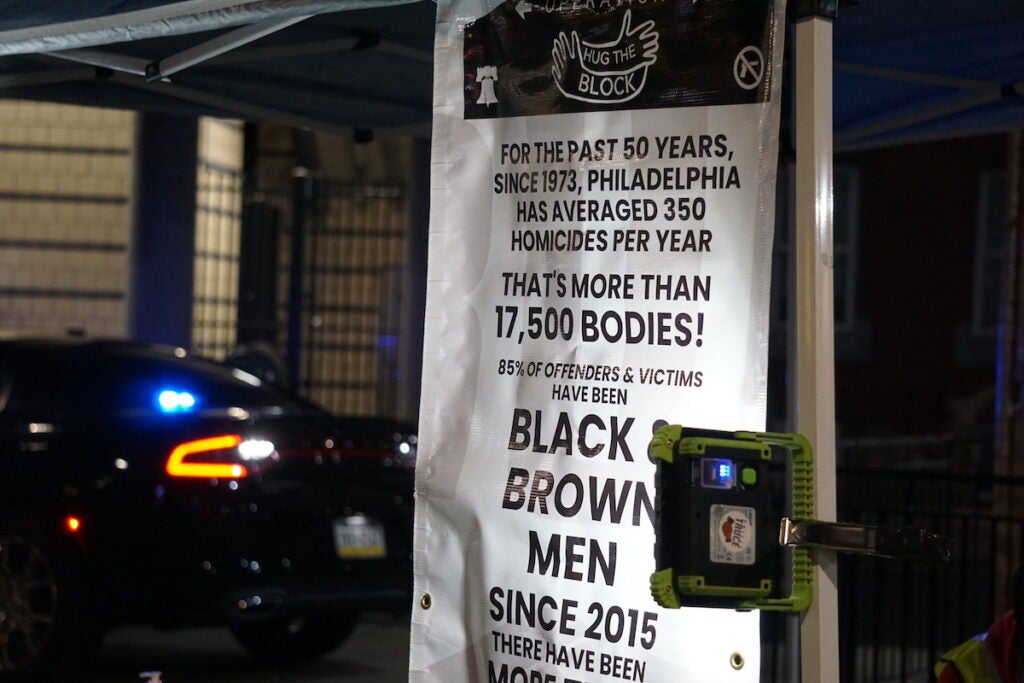

The intersection in front of Kensington’s Tioga Station is still busy, though some of the cars slow down, reading the signs attached to an EZ-Up tent. Jamal Johnson sits alone, handing out literature to anyone who passes by.

Johnson is serving as guardian of the base for “Operation Hug the Block,” a neighborhood watch program. By the time it concludes on Election Day, Operation Hug the Block volunteers will have patrolled 77 locations in Philly’s hardest-hit areas. The project is a collaboration between Johnson’s Stop Killing Us (SKU) and Philly TRUCE.

Around the corner, a call and response gets louder: “Operation hug the block!” “Operation hug the block!” “It’s the peace patrol!” “It’s the peace patrol!” Six men emerge, wearing lime green visibility vests over t-shirts and hoodies. There’s laughter during some brief ribbing about the proper amount of patrol time, and Johnson is reminded that he’s not in the Marines anymore, even though he acts like a drill sergeant.

The man with the megaphone is Emmanuel Bussie. “I’m trying to lead by example,” he explains. “There’s no way that we can stop the violence [or] curb the violence in an entire city. But what we can do is set the tone, to set an example [for] what it can take to actually turn this violent thing around.”

The difference between Hug the Block and similar projects, according to Bussie, is the focus on sustainability. “[The] process of men patrolling their own streets, men getting out and getting engaged, and getting involved at a higher level… we need to scale this. It can’t be just the seven or eight or nine or a dozen of us in one neighborhood, one block.”

At 11:05 p.m., Johnson gathers the group. “Let’s go, let’s go!” “You got some flyers?” Followed closely by a Philadelphia Police Department car, the men begin the calls and responses again, rolling up flyers before placing them in car door handles.

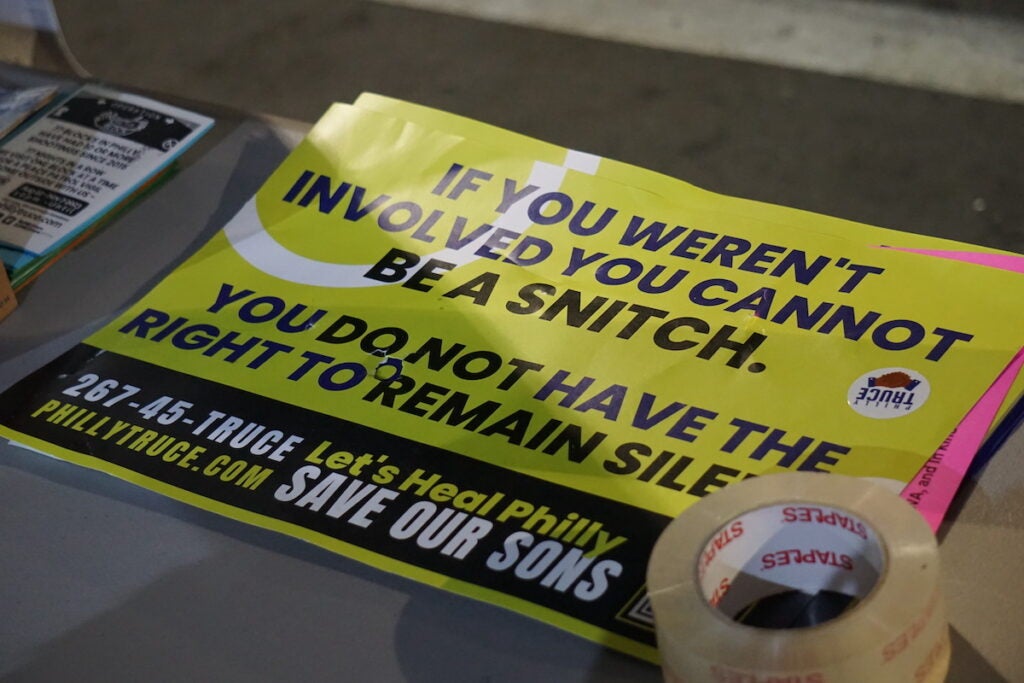

The group moves steadily, stopping only to hand flyers to cars that slow down, area residents walking by, and a surprising amount of people who open their doors. At one point, they step off the road and onto the sidewalk, where about ten people sit on a few couches and chairs, arranged in a circle. They’re hesitant at first, but most accept a flyer.

The patrol lasts about 40 minutes. “If you can hear my voice,” Bussie shouts through the megaphone, “that means you live in on or around one of the 77 most dangerous blocks in the city of Philadelphia. That should be unacceptable! Everybody has a role to play to stop this violence. This is one solution.”

A few people cheer the patrol on; some wave from windows. Johnson said the group has had a few negative interactions. “Of course, we’ve had our detractors, unfortunately, we’ve had threats about being out here, but overall we’re optimistic that we are getting done what we’re trying to do.”

On September 17, during the 1 a.m. Peace Patrol in a different section of Kensington, a man on a bicycle circled the area near the Hug the Block tent. Johnson and another volunteer were having a conversation when the bicyclist told them to leave because an unknown “they” would “clear this out.”

Johnson called the volunteers out on patrol, who came back to the base in a police escort. In response, twelve members of Philadelphia City Council denounced the threats on Monday. Councilmembers Kendra Brooks, Curtis Jones, Kenyatta Johnson, Jamie Gauthier, Sharon Vaughn, Isaiah Thomas, Katherine Gilmore Richardson, Anthony Phillips, Mark Squilla, Quetcy Lozada, Mike Driscoll, and Cindy Bass issued a statement denouncing the threat.

The statement read, in part: “We call on all Philadelphia community and faith organizations to show their support by joining one of their upcoming Peace Patrols. The volunteers of Operation Hug the Block are primarily Black men, and they spend their nighttime hours in the neighborhoods most impacted by gun violence, offering the visible presence of people who care and creating a space for safety, camaraderie, and community on some of Philadelphia’s most devastated blocks.”

The 12 council members committed to attending a patrol, and praised both Stop Killing Us and Philly Truce for “acting with the urgency that our gun violence crisis calls for and carrying forward a long tradition of Black, community-led violence prevention and mutual aid.” Councilmembers Quetcy Lozada and Kenyatta Johnson have already met with Hug the Block volunteers; Johnson walked with them.

“We’re asking people to change the way that the city has been going for the last three or four years with this gun violence,” said Johnson. “So when we come through and we encourage people to start being out in their communities again, to start being eyes and ears of the community, I’m sure there are people who don’t want that.”

Despite the long, late hours, Operation Hug the Block volunteers are determined to continue.

“We want the community to come back to the community again, not be held hostage by the violence,” Johnson said, sitting under the base tent. “We’re setting an example by going out here ourselves at night and encouraging people to do the same in the daytime. [We want] children to come back out and play again, old people sitting on the steps, women to be able to come out and not worry about being carjacked.”

The Election Day end date was not an accident, Johnson added. “We don’t feel they’re doing enough, and we hope that they will make this number one on their agenda after the next election.”

Operation Hug the Block is scheduled to send out Peace Patrols every night through November 7 from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. Volunteers are invited to join at any time and leave at any time.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.