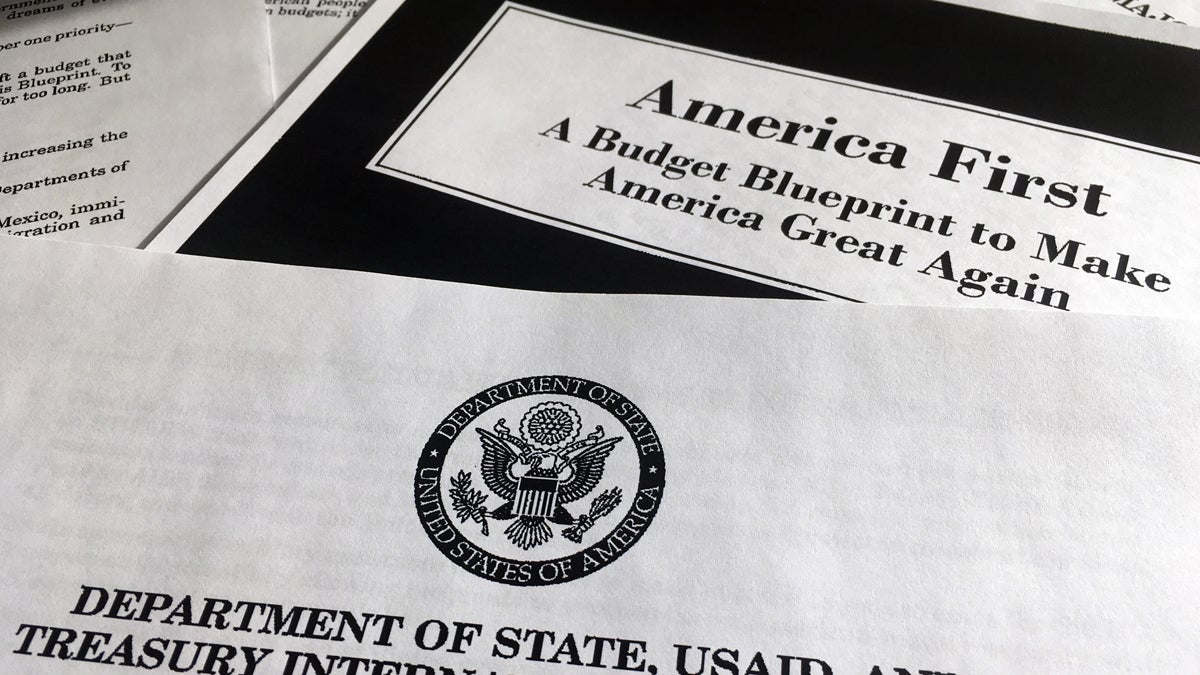

Attacking the NEA does not put ‘America first’

The budget blueprint for President Donald Trump's first budget and released by the Office of Management and Budget is photographed in Washington, Wednesday, March 15, 2017. (AP Photo/Jon Elswick)

I thought about my grandmother last week, when Donald J. Trump unrolled a federal budget proposal that, to no one’s surprise, contained not a penny for the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, or the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

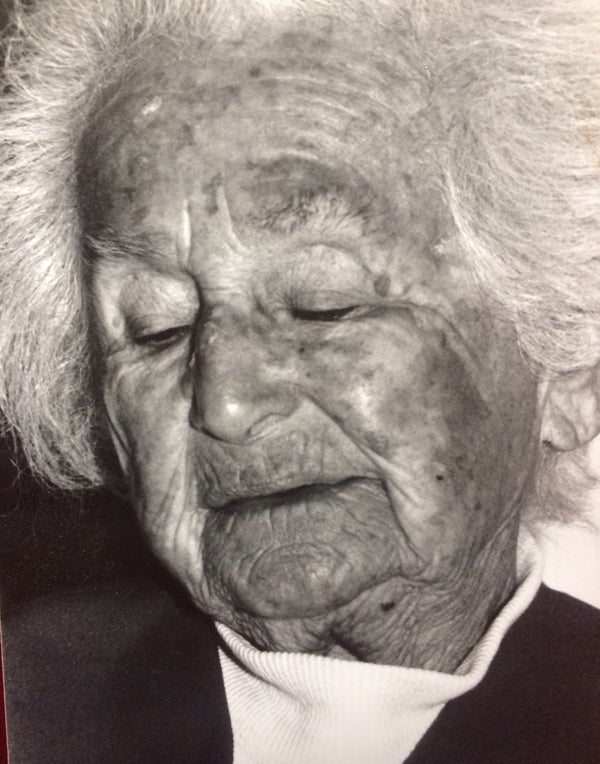

When I phoned my Bubie Rose on her 90th birthday, she called me shayna maidele (“beautiful girl” in Yiddish). Then she asked, “You know who I thank God for every day?” I tried to guess: Her family? The neighbor from apartment 12C who stopped by most evenings? The Belize-born caregiver who slept on the pullout couch?

“I thank God,” she declared, “for Eleanor Roosevelt!”

She believed that it was Eleanor who got FDR to push through the New Deal.

Rose, my paternal grandmother, never went to high school; her father insisted she go to work after 8th grade. But she knew shorthand and Shakespeare, wrote book reviews for the Rochdale Village newsletter, listened to Pavarotti, watched public television (“Upstairs, Downstairs” was a favorite) and yelled in exasperation whenever Nixon appeared on the nightly news.

I thought about Rose last week, when Donald J. Trump unrolled a federal budget proposal that, to no one’s surprise, contained not a penny for the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, or the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

And I thought of her again on Friday night, when Fox news commentator Tucker Carlson said he had no problem with axing the NEA, questioning why taxpayers should subsidize “entertainment for rich people” at a time of budget deficits.

Let’s get a few facts straight. NEA funding, $148 million in 2016, amounts to .004 percent of the entire U.S. budget. (Defense, on the other hand, gobbles about 54 percent of the discretionary spending pie.)

Do the math: You and I, Joe and Jane Taxpayer, foot the NEA bill for a mere 45 cents per person per year. Parking-meter change. And what do we get with those pennies, once they’re added up and divvied out, handfuls of coveted coppers, to every Congressional district in America?

We get the NEA Military Healing Arts Network, which supports creative arts therapies for service members with traumatic brain injuries.

We get Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky (in the heart of Letcher County, where Trump claimed nearly 80 percent of the popular vote), a nonprofit that uses film, music, theater, and digital media to capture the voices and culture of people living in Appalachia and rural America.

We get “An Octoroon” at the Wilma Theater. We get “Building Hero,” a multigenerational community design training program for youth and adults from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds.

We get Poetry Out Loud, a contest that challenges high school students to memorize and perform classic and contemporary poems, from the iambic pentameters of Shakespeare to the jab-in-your-gut free verse of Toi Derricotte, and concludes each spring with an ebullient run-off in Washington, D.C., as champion poets from each state compete for a $20,000 prize.

I’ve worked with some of those kids. As a teaching artist in the Poetry Out Loud program since its 2005 launch, I’ve coached students from Hoboken to Vineland as they select, analyze, memorize and perform pieces from a 900-poem online anthology compiled by the NEA and The Poetry Foundation.

At this year’s state finals, held March 9 at the College of New Jersey, the 12 contestants were a snapshot of America’s future: last names of Sparacio and Malik, Choi and Diaz, kids hailing from vo-tech institutes, public magnet programs, pricey boarding academies and sprawling regional high schools across New Jersey.

They included Emily Li, daughter of Chinese immigrants, junior at The Lawrenceville School, who captured the staccato wordplay and crowd-surge of energy in May Swenson’s “Analysis of Baseball,” and Breana Sena, who goes to Ronald E. McNair Academic High School in Jersey City and hushed listeners with her recitation of “I Sit and Sew.” That poem, written by Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson in 1920, releases the coiled rage of a woman consigned to tailoring “the little useless seam” when she yearns to act in the more public, urgent realm of war.

Amos Koffa stood above the rest — literally. He’s a 6-foot-3-inch, bespectacled, pipe-thin senior at the Burlington County Institute of Technology, and this year’s Poetry Out Loud contest was his third and final shot at becoming state champion. He performed each poem as if it were a musical score — voice plunging from shout to whisper, slender arms scooping air — enunciating the wild rap of Jack Collom’s “Ecology” until the final whoop of a “wing that whirls up over and out.”

“I Sit and Sew” reminded me of Bubie Rose, bitter all her life that her father steered her toward shorthand and typing classes rather than the literature and history she loved. At 93, she couldn’t tell me what she’d eaten that day for breakfast, but she could do Macbeth’s Act V soliloquy (“Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow/Creeps in this petty pace from day to day …”) and recite a Brooklyn-inflected “Hiawatha” by heart.

John F. Kennedy, who did not live to see the creation of the NEA (established in 1965, with bipartisan Congressional support and the signature of President Lyndon Johnson), once said, “The life of the arts, far from being an interruption, a distraction, in the life of a nation, is very close to the center of a nation’s purpose.”

Not a distraction. Not “entertainment for rich people.” Art — sculpture and sonnets, operas and one-act plays, mosaics in Philadelphia alleyways and mandolin ballads from the core of Trump country — is how we tell our story. Art can be a balm, a rant, a reveille, a metaphoric flag on fire. By the people. For the people.

At the end of April, National Poetry Month, Amos Koffa — child of Liberian ancestry raised by a single mother, LGBT activist, aspiring spoken-word artist and 2017 New Jersey Poetry Out Loud champion — will go to Washington, D.C., for the contest’s finals, an expenses-paid trip for which I am happy to pony up my NEA-directed 45 cents.

If my Bubie Rose were still here, she would dig into the pockets of her flowered housecoat and add a little extra change.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.