Older adults are the most socially isolated in America. How do we fix that problem?

According to the surgeon general’s 2023 report on loneliness, a lack of social connection is as dangerous as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Janada Carter hosts Bible Jeopardy for North Light Community Center, with a group of volunteers teaming up with the center members. (Nate Harrington/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

When Delilah Bryant-McCall’s husband suffered an aortic dissection — a split in the part of the heart that delivers oxygen enriched blood to the body — everything became too much. Her life was just worry. This state consumed her and her life: she stopped working and quit community college.

“I was isolating myself, staying home, doing nothing,” she said, looking out the window of the Philadelphia Senior Center – Allegheny a few weeks after her 71st birthday.

She had always considered herself a shy person, so she didn’t question her feelings of isolation and the lack of connection. But a conversation with her husband made something click in her mind.

“He said, ‘Are you depressed?’” Bryant-McCall said. “I had never thought about it. But I was. I was depressed.”

This phenomenon isn’t uncommon and, unfortunately, the outcome is expected. At least 29% of older people, those aged 50-80, said that they felt socially isolated in 2024, according to a University of Michigan study. Of those who felt isolated, 77% said their mental health was either fair or poor.

Among Americans of all ages, “the highest rates of social isolation are found among older adults,” according to the surgeon general’s 2023 report, Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation.

This isolation is only one of the problems older adults in Philadelphia face. For Philadelphians aged 65 and older, 23% live below the poverty line and 28.6% rely on SNAP benefits, both of which are at least 10 percentage points higher than the national average for the same age group.

It doesn’t help that “something that our society has ingrained in us that it’s not okay to ask for help or, you know, be an older adult,” said Katie Young, planning manager at Philadelphia Corporation for Aging.

Breaking through self-isolation

However, there are ways to combat loneliness and other problems seniors face. Organizations like Philadelphia Corporation for Aging and the Mayor’s Commission on Aging both are working to tackle these problems in Philadelphia in a variety of ways, often through programs in senior centers.

Still, the problems persist.

Like Bryant-McCall, Patricia Carter, a West Philadelphia resident, was isolating herself.

“After COVID was over, I was used to being isolated,” she said. “I continued to just stay to myself. I didn’t talk on the phone. I didn’t go out unless I needed to go to the market or something like that.”

Carter didn’t say it herself, but her daughter Janada Carter, who is the manager of the Star Harbor Senior Community Center, mentioned that her mom was showing signs of depression.

The link between depression and other mental afflictions and loneliness is strong, with the effects compounding, according to Jeff Kullgren, the director for the National Poll on Healthy Aging, which produced the Michigan study.

“Being lonely is a risk factor for other kinds of mental health conditions,” Kullgren said. “Also, similarly, when people are experiencing depression, you know that people are reclusive. They may feel more disconnected from other people. They may have trouble getting out.”

The main issue with identifying isolation in older adults is that “when people are experiencing loneliness, they’re less likely to be seen,” Kullgren said.

Physical consequences of loneliness

It’s not just mental problems that are tied to loneliness either, as social isolation can be also caused by physical health problems. More than 50% of the lonely respondents to the National Poll on Health Aging reported they were in fair or poor physical health.

The surgeon general’s report put it bluntly: lacking social connection is as dangerous as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Bryant-McCall not only felt this lack of connection, she had been leaning into it.

“I didn’t have nobody to talk to because I wouldn’t allow myself to talk to them,” she said. “I just went through the emotions of going through the depression stage and trying to figure out how did I get there and how to get out of it.”

She kept brushing away the negative feelings and social dissociation as her tendency to be shy. And it could’ve persisted, but she had a small lucky break.

“I overheard two ladies talking about the senior center,” Bryant-McCall said. And she decided to visit and find out what the hubbub was for herself.

One of the largest organizations that helps run and maintain Philadelphia-area senior centers is the Philadelphia Corporation for Aging, which they try to make as affordable as they can be for the area’s older residents.

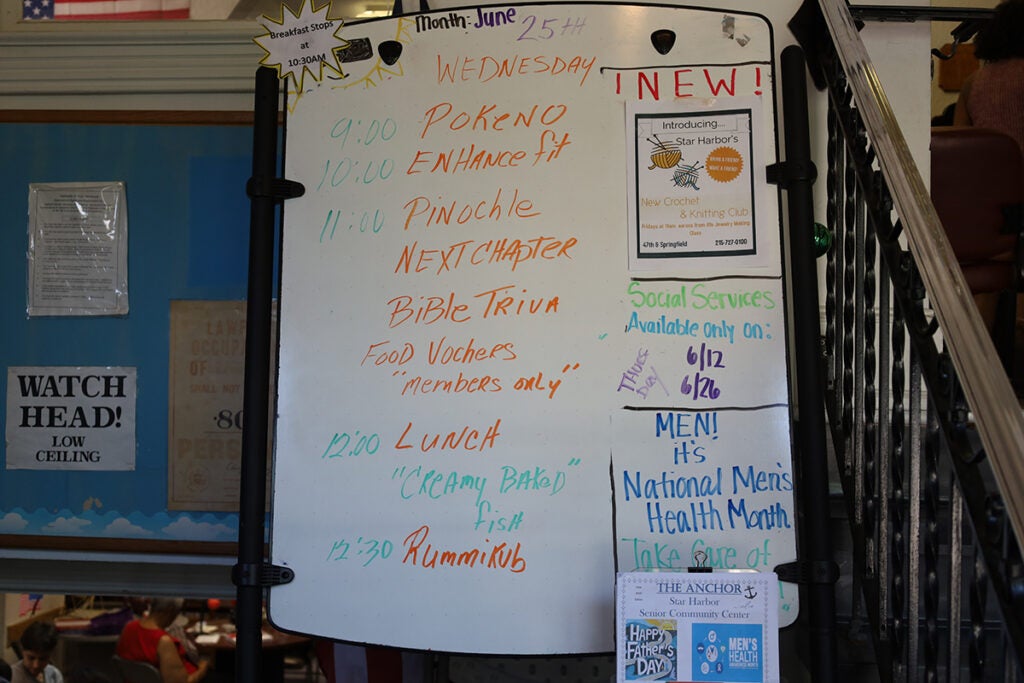

The organization supplies a variety of programming for the senior centers, Janada Carter said, and the Star Harbor center is completely free.

Activities range from playing games and trivia to having social workers answer questions and a person that helps seniors use their phones. The community center’s attendees have a decent amount of input, Janada Carter said.

This input is why the center usually devolves into a heated Rummikub scrum by the day’s end, she said. The group even occasionally competes against other senior centers, and the Star Harbor players “always win.”

Limited options for community connections

For many, these centers are the only place they can have friends and see people, Patricia Carter said, because “unless you go to the casino or belong to a church, you don’t really have an active social life.”

For many older adults this is the case: they lose the places where they can interact with people their age.

A senior center is a great way to mitigate that effect, but it’s not the only way. Many cities have places, like the Free Library of Philadelphia, that offer events geared towards seniors.

Having conversations with older adults about what they like and what they miss doing is one way a family member or caregiver can help older adults, Kullgren said. Another way is if you’re going to dinner or an activity, “think about asking the older person in your life if that’s something they’d like to join in on.”

He acknowledged that it can be difficult to get some older adults out there, but it is very beneficial as being out in the community “could be an opportunity for them to have social connections too.”

Benefits of a simple check-in

One solution “could be as simple as checking in more frequently,” Kullgren said.

Those check-ins matter. For Bryant-McCall, it was a wake up call from her husband that got the ball rolling on stepping out of her shell. For Patricia Carter, it was her daughter asking for her to call bingo over and over until Patricia relented and did so. For Martha Millikin, it was her nurse practitioner who recognized many of the same signs of depression and recommended Millikin go to Philadelphia Senior Center – Allegheny Branch.

Millikin was initially hesitant to go because she “expected a lot older people, that they’re grumpy and didn’t want to interact with people.”

She said that wasn’t the case as people came to interact and be around their community. Despite her visit being just two weeks earlier, visiting the center is now part of her daily routine.

“I like to get out of the house and have lunch with people,” Millikin said. “I like the interaction with people every day, you know? And it makes me feel like a whole lot better.”

Bryant-McCall also attends the Philadelphia Senior Center – Allegheny Branch. She goes as much as possible, joking that since her husband started working again, she’s had even more reason to come. Bryant-McCall especially enjoys the pottery classes she can take for three “activity coupons,” which comes out to about $3. The center itself has a $15 a year membership.

She is confident now, stepping out of her self-ascribed shyness, wearing a pair of earrings she made during the center’s jewelry making class, talking and laughing loudly in the dining area of the center.

The center “saved my life because it had things for me to do,” Bryant-McCall said. “Like to occupy my mind, to keep me from thinking about all my problems.”

Editor’s Note: Nate Harrington’s WHYY News internship has been made possible thanks to the generous support from the Dow Jones News Fund O’Toole Family Foundation Internship.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.