‘Okaeri’ shows how Shofuso Japanese house was built by cultural activism

The Japanese house in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park was saved 40 years ago by former inmates of Japanese internment camps.

Rob Buscher, curator of 'Okaeri: The Nisei Legacy at Shofuso,' on Turtle Island in the Shofuso koi pond. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The “ten mat” room of the Shofuso Japanese house in Fairmount Park is so named because it is the size of ten tatami floor mats. It now welcomes visitors to sit on those mats and watch a three-channel video projection, “Okaeri,” meaning “Welcome home.”

To the left are 8mm home movies taken in 1957 by the Japanese craftsmen who came to Philadelphia to build the Shofuso house. You can see the jumpy, hand-held camerawork of framing posts being cut and joined, and the koi pond being dug out.

To the right is video footage of the same house in 1999, being repaired by, again, traditionally trained Japanese carpenters.

In the middle is a slideshow of photographs and oral histories of the people that turned Shofuso into the centerpiece of Philadelphia’s Japanese heritage: the Nisei, or second-generation Japanese immigrants. Many of them had been forcibly incarcerated in internment camps during WWII for being perceived as threats to the war effort.

“One of the things I remember: I was four and a half or so and it was summer. I got chicken pox. It was horrible,” remembered Hiro Nishikawa in the slide show. “In these barrack camp buildings there was no air conditioning. It was hot as hell. The outside temperature in July and August was 115, 118 degrees. I was miserable.”

Nishikawa was recorded sometime in the late 1980s or 90s by the local chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) during a national wave of oral histories recorded by formerly interned citizens. Rob Buscher, the curator of Okaeri, said more than 10,000 people had finally agreed to tell their stories after President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Rights Act of 1988, which formally apologized and offered reparations to Japanese Americans interned during the war.

Before that, many Nisei never spoke about the camps.

“Most of their children had never heard them talk about it. When they said something about camp, they thought they were talking about summer camp,” said Buscher. “Most of the Sansei – the third generation, my mother’s generation – learned about this in high school from their history teachers, instead of their family members.”

Buscher only recently discovered all this material. The 8mm home movies were found in Japan by the descendants of Shofuso’s master carpenter Isao Okumura, who shot the film and brought it home with him.

Buscher learned of the oral history recordings from more than 30 years ago when they appeared at his doorstep inside a set of nomadic cardboard boxes.

“The JACL Philadelphia chapter, being a nonprofit civil rights organization, doesn’t have an office. The archives have moved from one board president to the next,” he said. “When I became the board president of our local chapter in 2018, I had several boxes delivered to my apartment by the previous president. This was one of the things that I found.”

Something else he found: many of the same people who formed the organization Friends of the Japanese House and Garden in 1982 to oversee Shofuso – known for its traditional construction and placid landscaping – were at the same time organizing nationally for Japanese American civil rights during the Redress Movement.

They included people like Reiko Nakawatase Gaspar, former president of the local JACL who developed education materials for Shofuso; Judge William Marutani, the first Asian American judge in Pennsylvania; and Grayce Kaneda Uyehara, who lobbied in Washington for Japanese internment redress and reparation.

Buscher said these people looked to Shofuso – which by 1980 had suffered deterioration and vandalism – as a needed space for Japanese advocacy and activism work in Philadelphia.

“We have Chinatown, right? We don’t have a Japantown here. There’s no Japanese temple, there’s no Japanese grocery store, there’s hardly any Japanese restaurants of that era,” he said. “So having a physical location for the community to gather, to be in each other’s company, and think intentionally about what it means to live in a place like Philadelphia, and how do we engage with other communities. That was a big part of the work they were doing.”

The Nisei who dedicated themselves to Shofuso had largely come to Philadelphia four decades earlier. In the years immediately following World War II, Philadelphia saw a Japanese population explosion. Once the federal government decided that Japanese American citizens in intern camps no longer posed a threat, the inmates were offered options for resettlement. Afraid of residual racist stigma on the West Coast, many looked east as a safer bet.

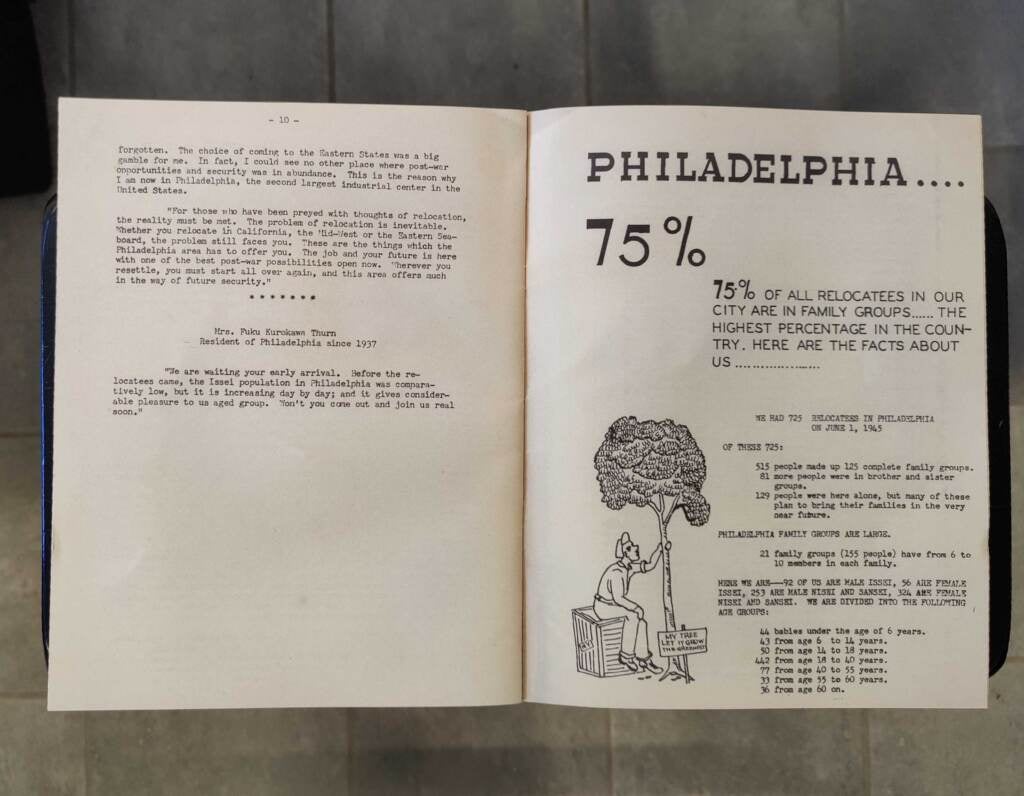

While still in the camps, they were given pamphlets describing various East Coast locations to which they might relocate, including Philadelphia. “Okaeri” includes reprints of those vintage pamphlets hyping Philly’s housing, education, job opportunities, and recreational facilities circa 1945.

“With two opera companies of its own, the New York Metropolitan Opera Company on Tuesday nights, and the world’s foremost musical stars upon the stage of the famous Academy of Music, it’s not surprising that Philadelphia has produced such artists as Marian Anderson, Nelson Eddy, and Jeannette MacDonald,” one of the pamphlets read.

The hype worked. Buscher said that before the war the number of people living in Philadelphia of Japanese descent was 42. After the war, it was 7,000.

The Japanese Americans also went to South Jersey in large numbers. During World War II Seabrook Farm was one of the country’s largest producers of frozen vegetables, but had problems attracting enough labor. The company proactively recruited Japanese Americans coming out of internment camps.

By 1946 there were about 2,500 Japanese Americans working in Seabrook, effectively becoming a kind of Japantown with a Buddhist temple and Japanese cultural center. Buscher said Shofuso House in Philadelphia would often invite cultural dancers and taiko drummers from Seabrook to perform in Philadelphia.

To acknowledge the Seabrook-Philadelphia connection of local Japanese heritage, Buscher included a vintage box of frozen broccoli from Seabrook Farms.

“There’s also a number of second- and third-generation Japanese Americans who don’t have any connection to that wartime incarceration narrative,” Buscher said. “Part of the story here is trying to explore some of that diversity within the Japanese American community and bringing us together across different immigrant generations.”

“Okaeri: The Nisei Legacy at Shofuso” will be on view until the house closes for the winter season.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.