New research reveals depth of Philadelphia’s eviction crisis

Like pretty much every other city in America, Philadelphia suffers an eviction problem.

Tara Jackson knows that all too well. Two years ago, this longtime resident of Germantown received an eviction notice from her apartment building. After trying to represent herself in landlord-tenant court—as most renters must—Jackson made a mistake. In the backroom of landlord tenant court, the building owner’s lawyer talked her into signing an unappealable and binding judgement by agreement before the case even made it before the judge. She claims that it later came out that her landlord’s case wouldn’t have held up because the gas bill had been the issue. To evict her, the landlord had claimed she wasn’t paying rent because a tenant can’t be evicted over an unpaid gas bill.

But without a lawyer by her side, Jackson signed away her rights and was forced to move out of her home. Now she’s hooked up with a lawyer at Community Legal Services and is fighting to keep her Section 8 voucher, which is jeopardized because of the eviction.

Every eviction case comes with its own personal story, the idiosyncratic details that set it apart. But even though Jackson’s case has its particularities, she knows just how common the experience has become in her community.

“I know a lot of people who’ve been evicted,” said Jackson. “It’s a widespread problem and it’s not right. That’s why people are out here in these streets now. The system had done them wrong or the landlord done them wrong. Something has occurred for people to be out here in these streets like this.”

The root cause, as in most cities, is that rents have risen while wages and income have stagnated. That national trend translates to Philadelphia, although according to new research from The Reinvestment Fund (TRF), the scale of the city’s eviction crisis is greater than previously suspected.

In an interview with PlanPhilly, TRF’s Ira Goldstein and Al Parker say that they launched their research project after reading Matthew Desmond’s “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.” The book takes an in-depth look at conditions in the low-income rental market in Milwaukee and finds previously unsuspected levels of eviction.

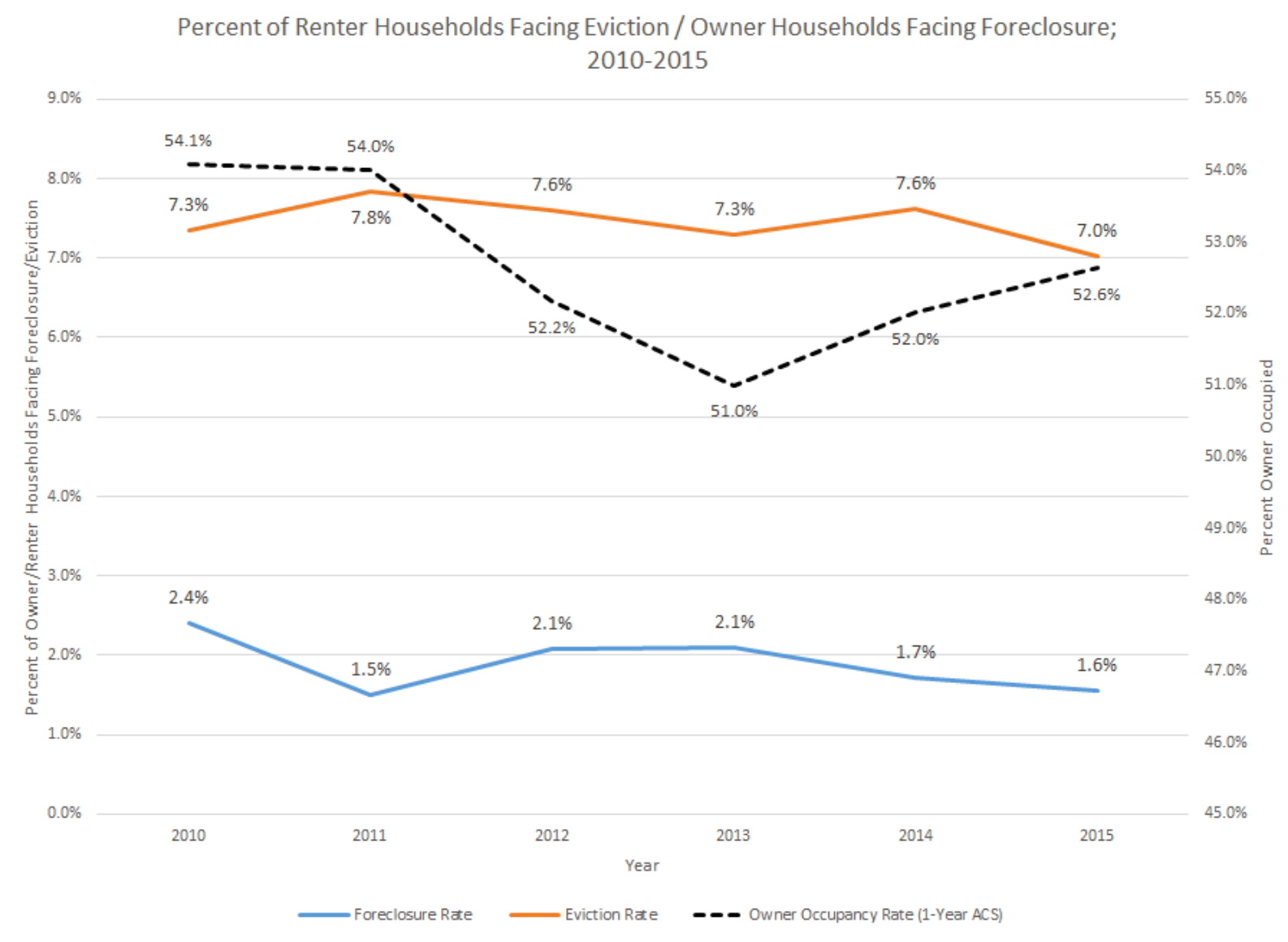

The researchers at TRF decided to try to measure the problem in Philly. After years of performing similar studies on foreclosure in the wake of the housing crisis, Goldstein and Parker anticipated roughly similar findings about eviction among renter households. Instead they found Philadelphia’s eviction rate never fell below 7 percent in the six years of study—2010 to 2015—which greatly outstripped the foreclosure rate that hovered between 2.4 and 1.5 percent.

“I was stunned,” said Goldstein, who believed that eviction and foreclosure rates might be similiar because Philadelphia has similiar numbers of ownership and rental units. “We have similar numbers of renter and owner occupied households, but we are finding [eviction] filings that are 4 or 5 times as great. [In some places], rates seven times as high, which outstrips Desmond’s numbers in Milwaukee. And we have every reason to believe this is an undercount because of all the people who pay rent in cash.”

TRF got its data from court filings, which are a wholly accurate way to measure foreclosures because there’s really only one way to get someone with a mortgage out of their house. There are, however, plenty of ways for landlords to expel tenants, which makes evictions harder to measure. Popular tactics include simply neglecting a property or threatening a tenant. Or, in an example lifted from Desmond’s book, taking the door off of its hinges.

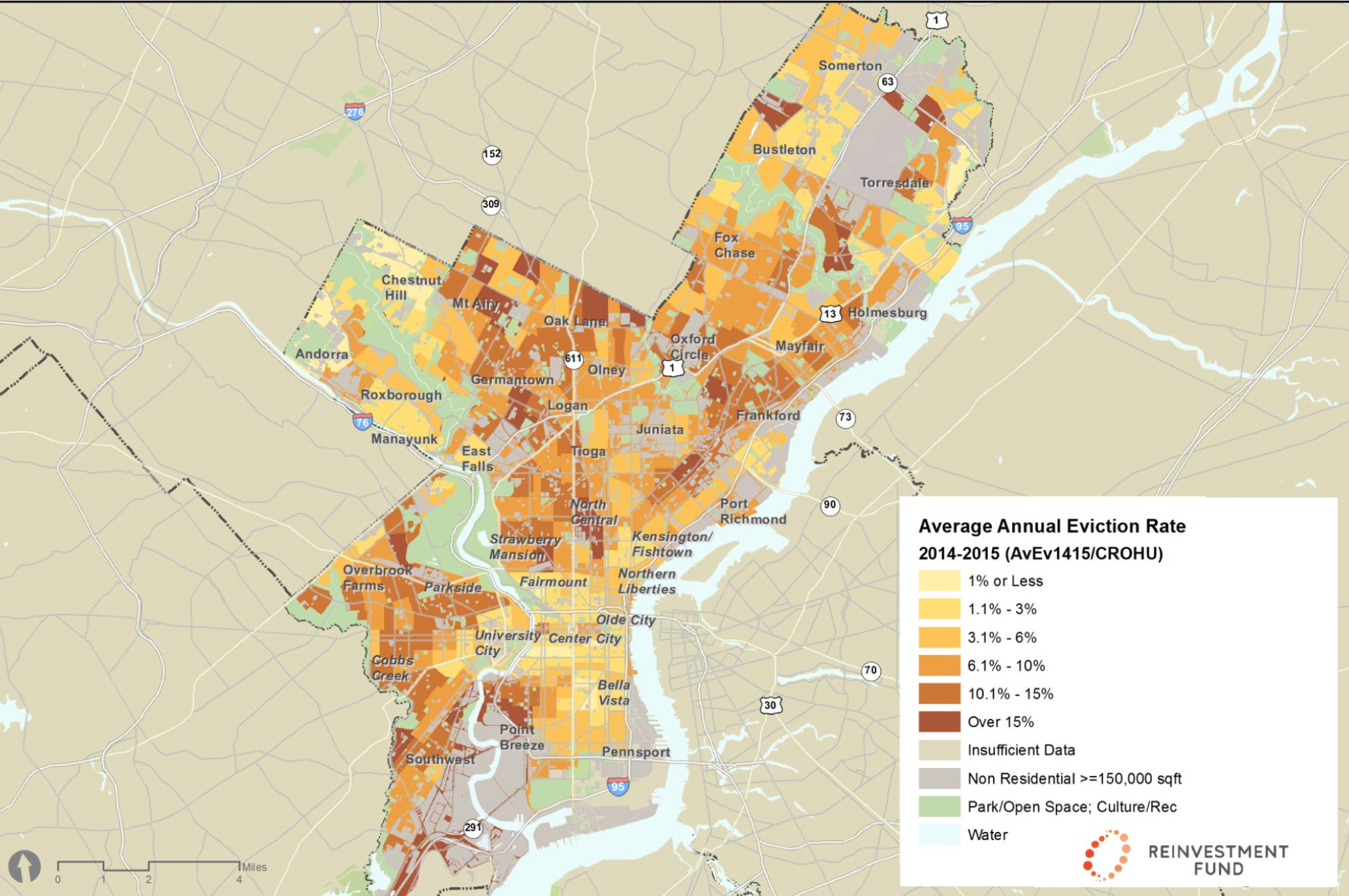

The TRF study also finds that there are large disparities in eviction rates among the city’s census tracts, varying depending on the geographic location and demographics. Much like in Desmond’s findings, Philadelphia’s black neighborhoods are hit hardest by the eviction epidemic. In 2015 census tracts that were at least 80 percent black had eviction rates of 10.2 percent, whereas those which were less than 10 percent black saw eviction rates of 3.3 percent.

The numbers are similar in every other year under review. Even when controlling for income and poverty, the eviction rates in majority black neighborhoods are still higher than in communities with different demographic composition.

Notably, the highest eviction rates are not exclusive to the poorest neighborhoods of the city. Although sections of North and West Philadelphia are among their ranks, the epidemic rages too in neighborhoods like East Mt. Airy, East Oak Lane, Germantown, and even in the Far Northeast. These worst hit census tracts have annual eviction filings of over 15 percent in 2014-2015.

“It’s very troubling when you see it in East Oak Lane, Germantown, East Mt. Airy, because they aren’t places where people think they need to pay attention” said Goldstein. “We know that evictions and foreclosures have a downward pressure on real estate markets. You also have the turmoil that comes with high turnover. If we don’t pay attention to what’s going on in these neighborhoods you have to fear for the future of the city.”

The neighborhoods Goldstein mentions have long been bastions of the city’s black middle class. In recent years, however, they have been facing new social pressures in the wake of the Great Recession, the foreclosure crisis, and the precipitous decline in public sector work.

The pockets of deep eviction pressure in the Far Northeast, which is known for its stability and its whiteness, are clustered around the boundaries of the airport and its adjacent industrial parks. Although the Far Northeast is dominated by single family detached housing, there are older garden apartments clustered in the areas of the region with high eviction rates. That could account for the epidemic’s tendrils in the Far Northeast, as could the surge in immigrant populations that have modestly altered the area’s demographics in recent years.

When eviction takes place on the kind of scale Goldstein and Parker have discovered, it morphs from being a tragedy for one household to a social problem that destabilizes communities. Getting evicted once makes it more likely that a family will be evicted again. For those who suffer the experience repeatedly it becomes harder for children to do well in school or for adults to hold down a job. In Desmond’s Milwaukee research, correlations were found between high eviction rates and high crime in neighborhoods. On the individual level, eviction is linked to higher suicide rates.

As much as eviction is tied to rising housing costs and stagnating incomes overall, the problem is further compounded, as in Jackson’s case, by the immense power imbalance between renters and landlords. The most obvious form this takes is in the lack of legal representation for renters in landlord tenant court. As a result, many people like Jackson are evicted even when the law may well be on their side because they are unable to adequately represent themselves against a lawyer or because they sign deals that may sound good in the moment but have lasting repercussions.

“A lot of landlords send their tenants to court for stupid things,” said Jackson. “You can bring all the proof you want but the judge is going to listen to them because they are the big corporation and we are just the small people. We just don’t have a voice.”

*This article has been slightly altered for clarity.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.