New Philly exhibit casts parallels between slave trade, modern sweatshops

The African American Museum in Philadelphia has opened a new art installation that links the African slave trade with modern-day sweatshop labor.

“Cash Crop,” by South Carolina-based artist Stephen Hayes, comprises several sculptural installations filling two galleries of the museum at Seventh and Arch streets.

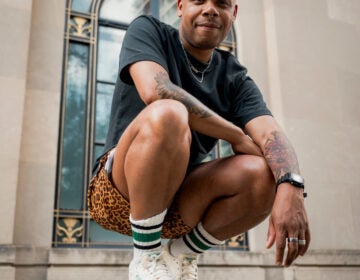

One room holds 15 life-size figures cast in concrete, molded from real people of African-American descent (the artist even molded himself). Each figure is chained to an image of the seal of the United States carved into the slates of a shipping pallet. Hayes forged about 500 chain links by hand.

He also cast more than 250 models of the famous Brooks Slave Ship diagram, a 18th-century etching showing that 450 captured Africans could be crammed into the hold of a transport ship, if each man were granted a space only 6 feet high by 16 inches wide, with a smaller space for a woman and even less space for a child. That’s for a trip across the Atlantic that took about eight weeks.

Each poured-metal cast of the Brooks diagram is set into a handmade wooden box about the size of a shoebox, stacked against the wall, floor-to-ceiling.

Hayes reworked the diagram of the slave ship into several pieces, including a poured-metal sculpture, several woodcut prints, and overlaid upon a printed map of slave trade routes.

Each piece looks rough, announcing to viewers that the artist, himself, labored over each element. The show represents thousands of hours of handwork.

“It’s all about putting my hand into it,” said Hayes. “I know there are people who make stuff that is about them not having to be part of the process. Everything you see — my fingers touched everything.”

Hayes says when he gets his studio set up to make multiples of something — like those 500 metal chain links, or pouring 250 molds — he works like a machine. At the same time, his work is critical of practices forcing people to work like machines. One of the pieces is a model of a slave ship with sails that are a patchwork of clothing labels indicating where they were manufactured: made in China, made in Indonesia, made in Korea, etc.

The museum curators did not overlook the fact that one of the gallery windows looks directly at a federal prison across the street, where incarcerated men are made to sew military fatigues by the thousands. Statistically, most of those men are black.

“You think about slavery, about personal experiences, and you think, ‘How could this have happened?'” said museum curator Leslie Guy. “And here I am, working here, walking by that building every day, and I don’t take into account how high our incarceration rate is. I hear the sounds, smell the smells, see the building. I’m in a similar situation.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.