Neighborhood Gardens Trust targets preservation for 28 more gardens

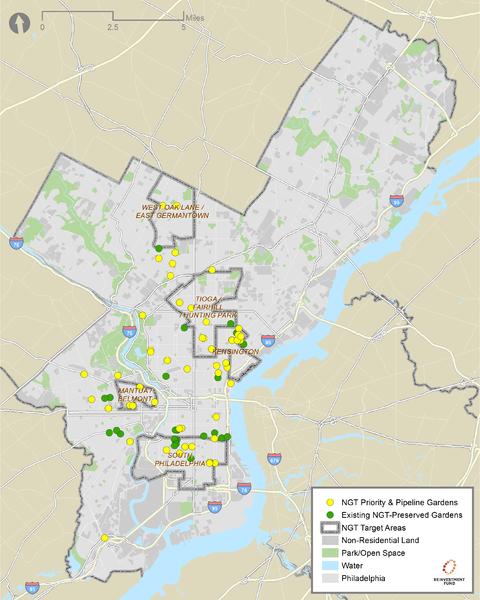

The preservation of community gardens and open spaces located in five areas of the city – Kensington, South Philadelphia, Mantua/Belmont, East Germantown/West Oak Lane and Tioga/Hunting Park/Fairhill – will be a focus of the Neighborhood Gardens Trust (NGT), based on a recently-released data-driven strategic garden acquisition study. The study was part of a plan to identify and prioritize community garden and open space preservation by NGT, a nonprofit affiliated with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS), to maximize the benefits to the residents of Philadelphia.

According to the Philadelphia Food Policy Advisory Council the city has at least 470 community gardens, but, as established in a recent Philadelphia City Council hearing, many of the gardeners are in constant fear of losing these spaces because they don’t own or legally control the land. Gardeners on certain city-owned land can only secure short-term, revocable license agreements, which are conditional on their ability to afford insurance coverage, according to NGT. And too often gardeners using privately-owned land cannot locate those owners, which is also complicated when properties are encumbered with tax liens.

“As Philadelphia’s real estate market is changing, and accelerating in some neighborhoods, the sense that community gardens are truly at risk is growing,” Jenny Greenberg, NGT executive director, told PlanPhilly. “We’re seeing gardens being built on for housing, or tax-delinquent properties within community gardens going to sheriff sale at an increased frequency.”

NGT is a nonprofit land trust that acquires existing community green spaces for long-term preservation. Since its predecessor organization, Neighborhood Gardens Association, was created in 1986, NGT has preserved 35 community gardens and shared open spaces. Their goal is to protect a total of 55 community gardens and green spaces by 2019.

After 18 months of research, a total of 28 gardens were identified as critical for their respective communities. Those are the gardens NGT will try to preserve next, either by acquiring the land, or through a long-term lease for the gardeners.

“These are the gardens we believe should be protected, because if NGT doesn’t move forward to preserve them, they may be lost,” said Greenberg.

Gardens by NGT Category

(click to enlarge)

To identify which gardens to preserve and acquire next, a research group – a committee that included open space and vacant land stakeholders, a group of NGT board members and staff, and PHS staff- analyzed spatial data, conducted focus groups and did public outreach with members of city agencies, nonprofit organizations, community development corporations, and neighbors. NGT worked with the Reinvestment Fund’s Policy Solutions Group and Ground Reconsidered as consultants, and the work was supported by the African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network’s Environments Supporting Healthy Eating community pilot program.

The team began by setting criteria for areas of the city most in need of community gardens and open spaces. The five areas were chosen based on limited access to supermarkets (using data from the Reinvestment Fund’s 2014 measure of Limited Supermarket Access), lack of walkable access to green space (more than a 15 minute walk, according to the Philadelphia City Planning Commission’s Measure of Walkable Access to Green Space), real estate market pressure (using values from the Reinvestment Fund’s Displacement Risk Ratio), concentration of low -and moderate- income households (using data from the 2009-2013 American Community Survey), and areas with high concentration of vacant land (block groups in which 15% or more of the housing units were vacant, according to the Philadelphia Department of Licenses and Inspections vacant properties database, 2013).

Next the they mapped existing gardens and green spaces in target areas, and confirmed this information through site visits. Out of 328 spaces in the five focus areas, only 73 were active and maintained. They also included gardens that were already working with NGT, even if they were outside of the targeted areas.

“The process of preserving and acquiring the gardens is a challenging one,” said Greenberg. Some of them comprise multiple parcels with different owners, and transferring their property is complicated. For the city-owned parcels, the process will start by submitting them to the Vacant Property Review Committee, then getting an approval of the transfer by the City Council and then going to settlement. That procedure that can take over a year, according to Greenberg. When the parcel is privately owned and has tax liens, NGT will work with the Philadelphia Land Bank to bring them to tax foreclosure, and then try to buy them.

NGT Gardens and Priority Gardens

(click to enlarge)

“Until NGT’s involvement, we were giving and investing only what we were ready to let go off,” said Julius Rivera, a gardener that has been working on the Collins Smith Barrick Play Garden in Kensington for 14 years. “Now we can really start dreaming and we’re already making dramatic improvements.”

Rivera said the garden, one of the 28 selected for the NGT pipeline, has a huge impact in the neighborhood, especially among kids, and that it has helped bringing together old residents with newcomers. But because the land is owned by the Redevelopment Authority, Rivera said he regularly has nightmares of losing the garden, dreams where he would look up the street and see bulldozers destroying the plots. According to Greenberg, with the support of Councilman Mark Squilla, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority board has approved the transfer of the garden to NGT. Now they’re waiting for the transfer to be approved by City Council.

“I’m still in disbelief and I’m still thinking that there’s going to be a problem,” Rivera said.

The Growing Home Community Gardens located in South Philadelphia (717-21, 726-30, 732-42 Emily Street, and 522, 528, 532-38 Mercy Street) are also in the priority list. Their situation is especially complicated because they’re spread across several parcels; some are owned by the City and others by private entities. Last summer, gardeners lost a portion of Growing Home when a private owner reclaimed some land for redevelopment.

“There’s a lot of anxiety in the community”, said Juliane Ramic, director of social services for the Nationalities Services Center, a nonprofit organization that welcomes refugees and manages these gardens. “We are in constant fear.”

The loss of the garden and the destruction of one of their fences by a bulldozer was very traumatic for the refugees, Ramic said. Most of them were farmers in their home countries – Burma, Bhutan, Nepal – and were already forced out of their land. “They see Philadelphia as the city that restored their dignity by giving them their land back,” Ramic said.

NGT already submitted a list of gardens to the Philadelphia Land Bank to acquire and is working with the City Council to get support for the transfers. The complete list of gardens NGT hopes to acquire was not released in an effort to protect these sites, but some in the pipeline are known: Mercy Emily Edible Park (521-31 Mercy Street), Holly Street Neighbors Community Garden (321-23 N. Holly Street and 320-22 N. 41st Street), and Emerald Street Urban Farm (2300-06 Emerald Street and 1937 E. Dauphin Street).

“The challenges now are the land assembly for those gardens and raising the resources to cover the cost of acquiring them and bringing them up to good condition,” said Greenberg.

The plan, made possible through a grant from the Community Conservation Partnerships Program of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, estimates that cost ranges from $26,000 to $42,500 per garden. This includes settlement costs, legal fees, insurance, administration and overhead, and investments in components that ensure the long-term sustainability and success of the gardens, like quality of fences, tool storage, compost and water access, lighting, bulletin boards and amenities such as common areas and trees.

NGT’s plan also quantifies resources to give technical support to gardens that are not ready for preservation today, but might be ready in a year. And Greenberg said that NGT is still interested in protecting community gardens outside of the target areas.

“There’s a shift,” Greenberg said. “Sometimes in Philadelphia’s history, community gardens have been thought as interim uses until we put a building in. This attempts to really focus down on preservation of gardens, to make sure that even neighborhoods that have seen a lot of redevelopment will continue to have this vital green spaces that serve the community.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.