Nearly 150,000 in Pa. could be forced to change medications beginning Jan. 1. Here’s why.

The state says the regulations will cut down on health-care costs, but many physicians are concerned they could harm patient care.

(iStock Photo/Philadelphia Inquirer)

This story originally appeared on Spotlight PA.

Spotlight PA is an independent, nonpartisan newsroom powered by The Philadelphia Inquirer in partnership with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and PennLive/Patriot-News. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter.

Nearly 150,000 Medicaid recipients in Pennsylvania could be forced to change their prescription medications in the new year, the result of new regulations that the state says will cut down on health-care costs but that many physicians are concerned could harm patient care.

Beginning Jan. 1, the State Department of Human Services will require the eight companies that manage pharmacy benefits under Medicaid in the state to use the same preferred prescription drug list — essentially, drugs that will be automatically covered — instead of their own individual lists.

As a result, some drugs currently provided will no longer be available without a special exception. That could force an estimated 150,000 of the state’s 2.8 million Medicaid recipients to switch to new medications, state officials said. Among that group, approximately 40,000 could have to switch multiple medications.

The change is widely seen as beneficial in the long term, simplifying care and decreasing health-care costs. The preferred list prioritizes cheaper options and makes them automatically available, while requiring doctors to seek special approval for coverage of more expensive drugs.

The Department of Human Services estimates that the new approach could save the state $85 million a year. Although there is some disagreement over that figure, physicians say the real concern is that the quick rollout of the new list could delay access to critical medications.

Some of those affected may find a drug similar to their current medication on the new list, but not everyone will find an appropriate replacement, said Mary Stock Keister, president of the Pennsylvania Academy of Family Physicians and a practicing doctor at a family health center in Allentown.

“I worry there will be gaps in care,” Keister said. “We always have to balance cost savings with the danger to patients of changing medications. I hope this doesn’t change what I do in seeing patients and deciding on the best option for them.”

For instance, Keister said, the new list is missing certain concentrations of long-acting insulin that she recommends to many of her diabetic patients, and it has only one class of oral osteoporosis medication.

Ed Balaban, a licensed physician and a consultant for the Penn State Cancer Institute, said the new list doesn’t include intravenous immunotherapy drugs that are commonly used for cancer patients. Although there are oral cancer drugs on the list, those work differently, he said, and in some cases, the two are more effective when combined.

More choices also allow patients to find a medication with the fewest side effects, he said. And in a field such as oncology, where new drugs are rolled out every few months, the fact that the drug list will be updated only once a year means the latest treatments will be missing.

“The unfortunate reality in medical care is a lot of decisions are economically based rather than therapeutically based,” Balaban said.

The new drug list — compiled by a committee of doctors, pharmacists and consumer representatives — doesn’t prevent patients from accessing other drugs, but it makes it harder. To get an off-list, or “non-preferred,” drug, a doctor has to submit a request to the company that handles pharmacy benefits, justifying the need for that medication, and the company needs to approve it.

Many physicians worry that their requests will be denied because the state, under the new regulations, is requiring the companies to adhere to the preferred drug list 95% of the time. If they fall below that rate, the companies could face fines starting at $1,000 a day.

“In order to get the highest number of people on the preferred drug list, I worry there will be a tightening of what will be approved for off-list use,” Keister said.

Sally Kozak, deputy secretary for Pennsylvania’s Office of Medical Assistance Programs, said the state’s goal is not to penalize companies. Monitoring for compliance won’t begin until July 2020, she said, and if off-list medications are approved for true medical necessity, it won’t count against the companies.

Even if the state finds improper approval of off-list medications, she said, the first step will be to have a conversation rather than simply issue a fine. Still, at a Senate committee hearing in October on the new preferred drug list, physicians said the 95% threshold was a significant concern.

In written testimony, Johanna Kelly from Reading Pediatrics Inc. said that medicines used for children with autism or mental illness almost always require special approval.

“We will exceed our 5% allowed very quickly,” she wrote, “and if this population of children do not remain on their medicine or can’t get medicine they need, we will have a disaster on our hands.”

Even if requests for off-list medications are approved, Balaban said, waiting for the approval creates a delay. In surveys by national and local physician groups, doctors say the approval process delays necessary care about 90% of the time.

“Cancer patients may not have that kind of time frame to wait and see,” Balaban said.

The Department of Human Services said it has tried to account for these concerns by grandfathering in some medications, meaning that people who were already using certain drugs that are no longer on the list will be allowed to continue without special approval.

That significantly reduced the worries for many pediatricians, said Deborah Moss, president of the Pennsylvania Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Still, other physicians say they’d prefer the compliance rate be lowered to 80%.

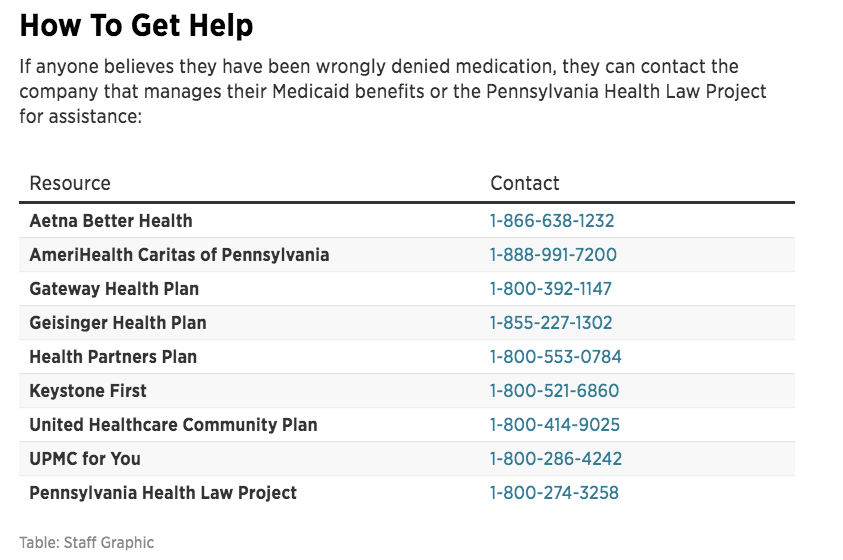

Patients affected by the change were notified by mail this fall and given a list of any medications that would need to be changed. And if patients run into issues come Jan. 1, there are laws in place to protect them, said Laval Miller-Wilson of the Pennsylvania Health Law Project, which provides free legal counsel to Medicaid recipients.

Patients can request a 15-day emergency supply of their old medication while figuring out how to move forward with their doctor, he said.

Spotlight PA receives funding from nonprofit institutions and readers like you who are committed to investigative journalism that gets results. Become a Founding Donor today at spotlightpa.org/donate.

Spotlight PA receives funding from nonprofit institutions and readers like you who are committed to investigative journalism that gets results. Become a Founding Donor today at spotlightpa.org/donate.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.