Native American comic artists tell story of 1763 massacre of Conestoga tribe in Lancaster, Pa.

“Ghost River,” commissioned by the Library Company of Philadelphia, tells the story of the 1763 slaughter of Conestoga from the perspective of the tribe.

In this illustration, angry settlers approach a Conestoga village, where they murder all the inhabitants. (Weshoyot Alvitre)

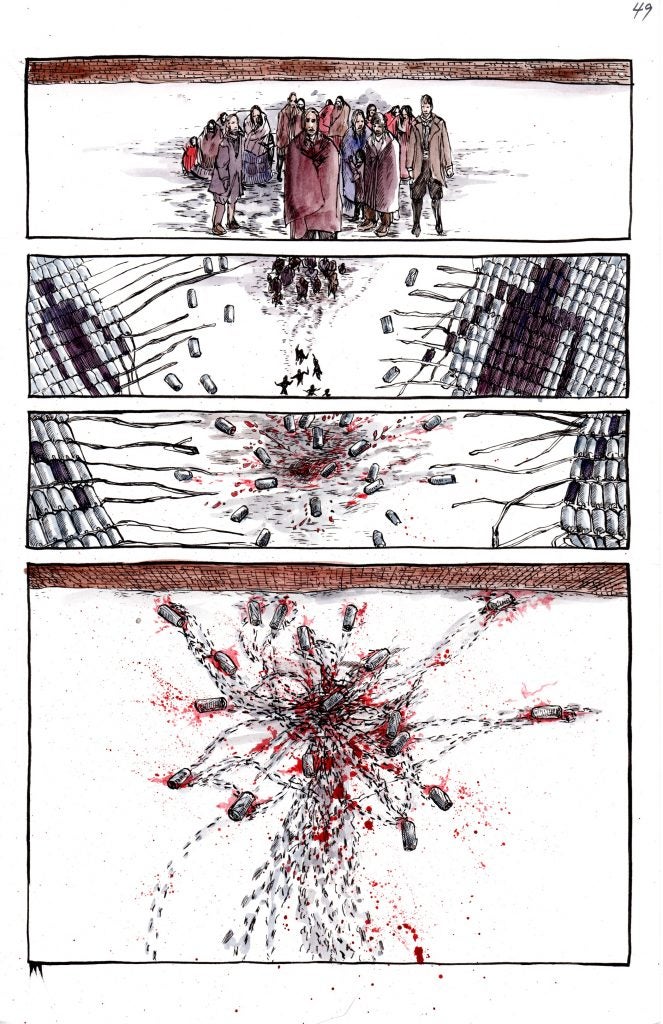

Action, fight scenes, and violence have long been used to sell comic books. But when two Native American comic artists took on the true story of the Paxton Boys’ 1763 massacre of the Conestoga tribe in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, they decided they didn’t want violence to be the focus.

“The landscape of film and TV that shows dead natives is hip-deep. You wade through it,” said Lee Francis IV, a New Mexico-based writer of Pueblo descent. “We didn’t want to do that. We didn’t need to fetishize what happened.”

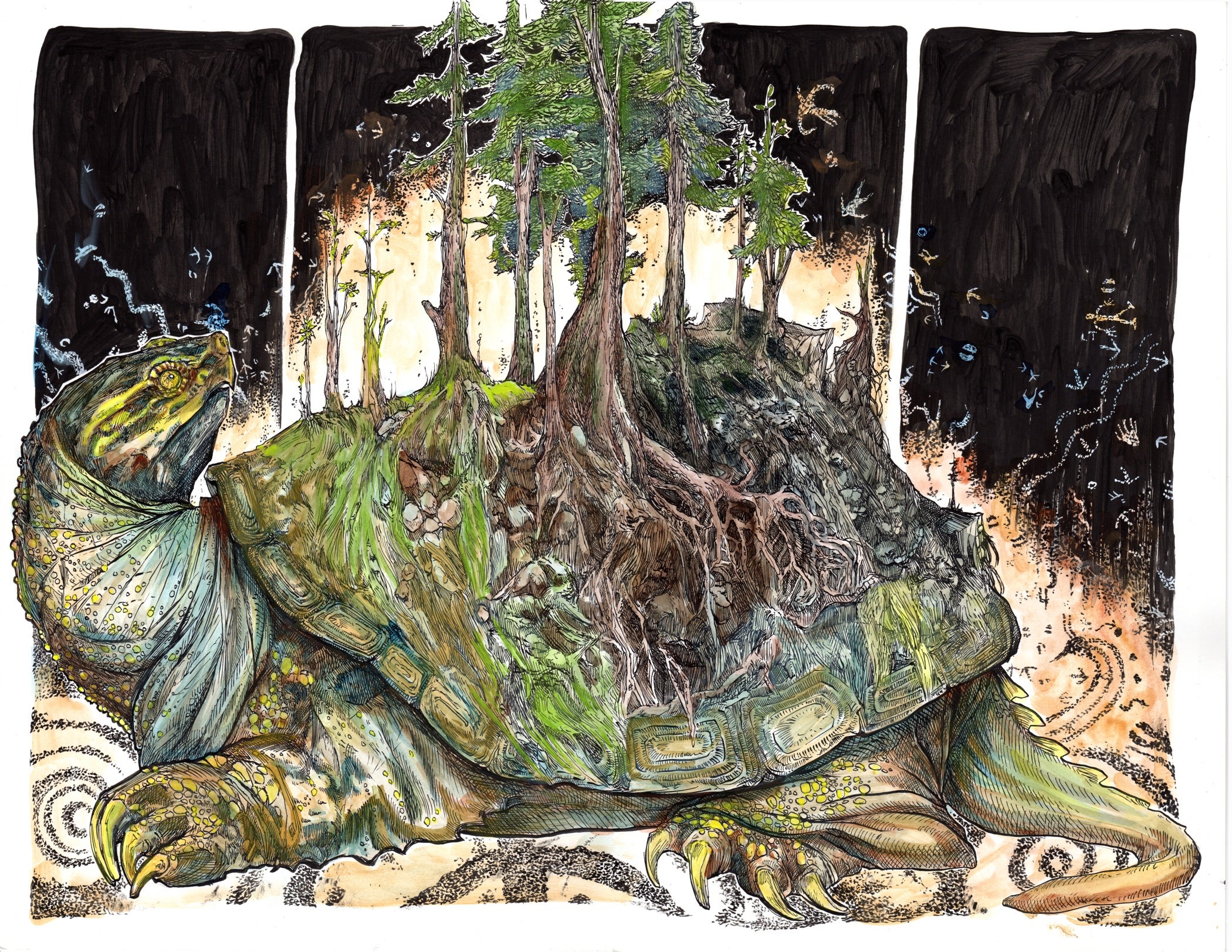

Instead, for the graphic novel “Ghost River,” Francis and Tongva illustrator Weshoyot Alvitre told a story of the Conestoga tribe, who were living alongside and trading with European settlers before they were murdered by a group of white vigilantes called the Paxton Boys.

On December 14, 1763, the Paxton Boys attacked a Conestoga town, killing six people and burning down their cabins. Governor John Penn offered the remaining Conestoga shelter in Lancaster, but on December 27, 1763, the Paxton Boys struck Lancaster as well, killing 14 members of the tribe, including women and children.

“Ghost River” depicts the massacre with a series of panels showing a wampum belt torn apart, its loose beads falling into blood-streaked snow.

“The wampum belt metaphorically depicts the trust and treaties between the colonists and the Native American people,” said Alvitre, who is based in Los Angeles. “I was trying to think of a way of tackling this without being graphically violent.”

“Ghost River” toggles back and forth in time, bouncing between the events leading up to the massacre and events that followed. Some of it is set in the present day, as the authors included themselves in the book and the process they took to make it.

“Native time constructs are non-linear and cyclical,” said Francis. “Our ancestors are always with us and time is fluid.”

Commissioned by Library Company

“Ghost River” was commissioned by the Library Company of Philadelphia, which holds a trove of historic documents related to relations between white colonists and Native Americans, the massacre itself, and the public arguments that resulted.

The graphic novel is part of a project to digitize all the documents — including political cartoons, pamphlets, broadsides, and manuscripts — and make them all available and searchable on an online portal. “Digital Paxton” currently contains almost 3,000 pages of historic documentation.

Will Fenton, the Library Company’s director of innovation, created Digital Paxton to push library science beyond academic circles.

“It used to be that a lot of cultural institutions were really gatekeepers of information. It was a rarified audience that had access,” said Fenton. “We really are moving toward opening up our collections.”

When Fenton approached Alvitre to be part of the Ghost River project, she jumped at the chance.

“If we did this book on our own, we wouldn’t have access to that stuff,” she said. “It’s often gated off to anybody but academics.

Alvitre’s father, Art Alvitre, worked in the 1970s and 80s to revive the culture of the Tongva, or Gabrielino tribe of Southern California, including its language. He was denied access to early Tongva language recordings on wax cylinders, held in archives meant only for researchers at accredited academic institutions.

“In doing research on his own tribe, he came against walls,” said Alvitre. “He had no access to wax cylinder recordings at Berkeley.”

As with most libraries, the archive at the Library Company favors the written historical record, a record that predominantly reflects the perspective of white colonists.

Alvitre and Francis did not limit themselves to that archive. They incorporated the oral history of the Conestoga that still exists at the Circle Legacy Center, a tribal advocacy organization in Lancaster, and from Curtis Zunigha of the Delaware tribe in Oklahoma.

“This stuff was passed down from person to person to person to person over time,” said Francis. “That’s the most valuable reference for us.”

“There was one thing they said, again and again, when we met them: We’re still here,” said Fenton. “That was the lodestar of this project.”

“Ghost River,” to be released widely in December, is part graphic novel and part study aid. The back half of the book includes reproductions of original documents and their summaries and a dialogue among the principles behind the project which describes the research and creative decisions they made to bring underrepresented voices to the page.

Fenton plans to distribute copies of the book to area libraries, as well as every native tribal community in the country, even ones that are not officially recognized.

“In Pennsylvania, there are no federally-recognized tribes,” he said. “We have no means without an organization like the Circle Legacy Center to get that volume out to the communities that might have the greatest stake in this story. We have a lot of work to do.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.