My Climate Story: Philly students take science from abstract to personal

A climate education and storytelling project helps students and teachers learn about climate change’s impact "in everybody’s backyards."

Listen 1:11

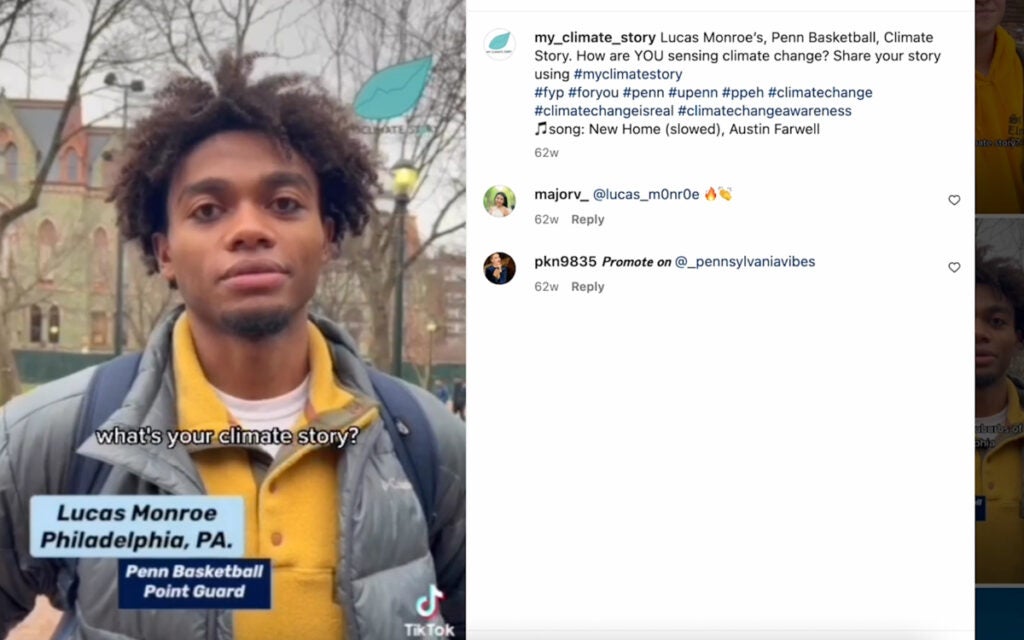

The idea for “My Climate Story,” a University of Pennsylvania public storytelling project in which students relate to climate change personally, is credited to public research intern Maria Villarreal, who started producing similar videos independently in 2022. (WHYY News)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Climate change may be a big topic to comprehend, but young people are paying attention.

Changes are felt in many ways, such as warmer winters, worsening floods in coastal cities like Atlantic City, and ever-increasing insurance premiums. “My Climate Story,” a University of Pennsylvania public storytelling project, wants to help middle-to-high school students connect the dots with personal experiences.

“Climate change is showing up in most people’s, everybody’s, backyards and places that they love,” said Bethany Wiggin, program leader at Penn’s Environmental Humanities department.

The university funded the project through the Environmental Humanities Department, and a $50,000 grant was divided between participating classrooms. The cohort of teachers met monthly for a year to map out their lesson plans. Since it began in 2019, the program has expanded.

“My Climate Story” deployed the “Campus Correspondents” initiative in March. Under this initiative, a group of 12 students will capture, produce and share personal stories across TikTok and other social media platforms. The first round attracted more than 40 applicants.

According to a press release, “These correspondents will not only amplify the voices from their own communities but also strive for administrative and policy action in favor of an increase in resources dedicated to climate literacy in higher education.”

The idea is credited to public research intern Maria Villarreal, who started producing videos independently in 2022. Her community in Tampico, Mexico, has been impacted by a refinery’s pollution and environmental degradation where fishing is a primary source of income.

“Something that might seem enjoyable to you, like longer summer, shorter winter, being able to go to the beach more, there’s so many impacts in the ecosystem surrounding that affect marine life,” she said.

In the last month, Villarreal held training workshops for new correspondents. She said her goal is to make the videos compelling and consistent.

“It’s been a long process but a fun one,” Villarreal said.

Campus Correspondents can be based anywhere. For example, one of their latest videos features a student in Puerto Rico. Although Spanish-speaking videos are a first step, Villarreal wants to expand the project to include more people who speak other languages.

@ppeh_lab Jarelis’ Climate Story at Interamerican University Arecibo Campus in Puerto Rico. Thank you Keithlyn (MCS Climate Correspondent) for sharing their story with My Climate Story. How are YOU sensing climate change? Share your story using #myclimatestory #fyp #foryou #penn #upenn #ppeh #climatechange #climatechangeisreal #climatechangeawareness #puertorico #puertorico🇵🇷 ♬ original sound - My Climate Story

How the program evolved

On an 83-degree day in April, teachers and their students reflected on how the program taught them how to make climate change more personal. The program is part of a grant that gives schools in the region tools from which educators in any subject can benefit.

Courses are embedded into classrooms across subjects, even if they are not science or climate-specific. Educators apply and, if accepted, are given material to guide their classes. Mariaeloisa Carambo, a former high school history teacher and current PhD candidate at Drexel University, was one of the educators selected.

“There was a gap in the type of social justice I was teaching,” Carambo said. “We need to organize at the grassroots level, reminding government and agencies that people exist at the end of these bills and laws. How do we want to sustain life on this planet? And what kind of life do we want, too? I think the important thing is also quality of life.”

Each participant had a personal story to tell about how the world was changing before their eyes.

Carambo, a daughter of immigrants, recalled the wildfires from this past summer and not being able to travel to the woods she frequented as a child. It was “jarring,” Carambo said.

Carambo also has two young children, ages three and five. She has wrestled with the tension of caring for the earth to sustain human lives versus the history of extraction.

“As a mother, thinking about what my kids are going to experience when they’re my age, I’m getting emotional,” she said. “How do we also teach our children not only survival skills but the ability to … reposition yourself in society? So you can survive as these environmental justice issues get worse?”

Joni Woods, an English teacher at Academy at Palumbo, wanted the chance to teach how issues overlap. Woods was surprised at how little climate education is taught in Philly’s schools.

Her application posed this question:

“Why should English be an island of thought when stormwaters from the Schuylkill can cause our schools to pivot to remote learning?”

In her classroom, Woods’ taught how historical figures and movements addressed climate issues in the past.

“We did a little research on the Dust Bowl, the ozone layer, or just EPA regulations after the 1970s,” Woods said. “It was really fun to see how hopeful students were when they realized that we actually have a history of addressing climate change. It’s really important to leave students with tools, not just spread awareness. They have to know what actions they can take.”

The program allowed her to network with other educators, like Carambo, in the 2022 cohort who care about teaching about this topic.

“If this gets people thinking about climate change curriculum, then this will have done the job,” Woods said.

Student impact

Students like Hager Alsekaf, an 11th grader at Masterman, felt more confident talking about the topic with friends and family. But Alsekaf suggests keeping it simple.

“Trying to understand what they already know and what they don’t know so that you don’t overwhelm them or make them feel like they’re like any less for not knowing,” she said.

Other students, like Isabella Smith-Santos, said learning about climate change gave her confidence to make small changes in the day-to-day. Smith-Santos’ personal story juxtaposes her grandmother smoking on her porch with a plume of smoke trails behind a bus driving by.

She shared a message.

“Try to help the world in your own way,” Santos said. “Take responsibility, but also maintain a sense of empathy for all others. Don’t worry about what others will think of what you do for the world, just worry about what you’re doing for the world.”

Climate connection in three words

Q: What three words come to mind when you think about climate change and your community?

- Mariaeloisa Carambo: Organizing, future and life

- Joni Woods: Collaborative, equitable and all-hands-on-deck

- Hager Alsekaf: Heat, snow and community

- Isabella Smith-Santos: Responsibility, action and empathy

- Aster Chau, Academy at Palumbo, 9th grade: Community, intergenerational and people-power

- Maria Villarreal: Environmental injustice, exploitation and unity.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.