Philly museum reopens with new name & old treasures

The first thing visitors see when they enter the newly renovated Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent (formerly the Atwater Kent Museum) is the welcome desk. They already are seeing history.

The wood from which the desk is made comes from the bell tower of Independence Hall, itself undergoing renovation.

“The cladding inside the tower, dating from 1820, has been taken out,” said the beaming executive director, Charles Croce. “We repurposed some of it for the welcome desk.”

The museum on 7th Street closed to the public three years ago for top-to-bottom interior renovations, expected to be completed this summer.

It also spent that time overhauling its mission.

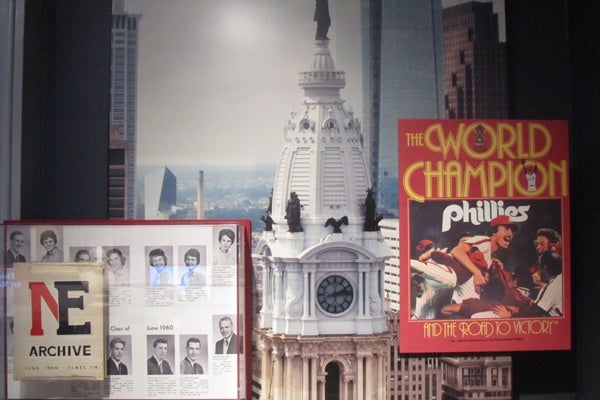

Beginning Wednesday, the museum will open two ground-floor galleries — the only ones yet completed — to the public. The free sneak-peak opening includes the orientation gallery with its quick overview of the 331-year history of Philadelphia, from slave shackles and the surveying equipment that determined the original parameters of the city, to posters of the Phillies’ 1980 World Series win and political buttons for Mayor John Street.

It also includes video monitors with testimonials by current city residents, produced by Philadelphia Community Access Media or PhillyCAM, the new next-door neighbors.

“My parents raised me at 11th and Vine in Chinatown,” said Albert Lee in the video presentation. “I went to grade school at Holy Redeemer at 10th and Vine and went to high school at Roman Catholic at Broad and Vine. So, for 17 years of my life, I spent it in three blocks.”

The other gallery will be devoted to community groups, which will be invited to install exhibitions about their particular neighborhood history.

Adding to 20th-century collection

The overhaul of the museum included making it more relevant to neighborhoods and contemporary visitors. Croce says the 100,000-object collection is strong in 18th- and 19th-century artifacts, but weak on the 20th century. Curators are proactively adding modern artifacts while purging objects deemed unnecessary.

“Up until 25 years ago, there was no curator,” said Croce. “Things were sort of dropped off, if you will, and became part of the collection that may or may not have had relevance to it.”

The ethics of purging objects from a public institution — called de-accessioning — is carefully outlined by the American Association of Museums. The guidelines insist the money accrued from sales of objects in a collection should go toward acquiring other objects, or toward the maintenance of the remaining collection.

Recently the museum sold “Yarrow Mamout” (1819), a portrait of an African-American Muslim by Charles Wilson Peale. The Philadelphia Museum of Art bought it for an undisclosed price. That painting came into the museum’s possession in 2009 from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Croce says money from the sale of objects such as “Yarrow Mamout” is going toward the renovations and for climate-control equipment that will protect the whole collection. It has never been properly stored.

“We were able to assemble the collection, which was, prior to several years ago, stored in warehouses with no humidity controls. Five of them all over the city,” said Croce. “We now have an off-site facility, state of the art, to care for and secure Philadelphia’s historical artifacts.”

With the renovated and climate-controlled spaces, objects from other institutions can be borrowed and safely displayed in the Atwater Kent building.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.