Measles in 2019: We’ve forgotten how bad it can be, pediatricians say

Vaccines worry a lot of parents. Pediatricians understand that, but they worry we’ve forgotten just how sick kids can get without the shots.

Listen 4:09

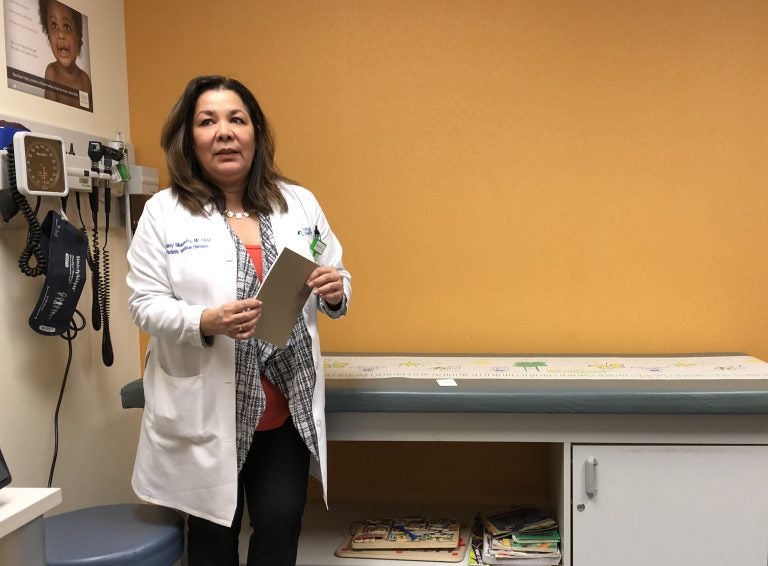

Dr. Tibisay Villalobos-Fry is a pediatric infectious-diseases specialist at Lehigh Valley Reilly Children’s Hospital in Allentown. (Christine Fennessy for WHYY)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

Olivia Pile is only 4 years old, but when her pediatrician, Scott Rice, asked if she knew why he gives her shots, she answered immediately — and with a big smile.

“So we don’t get sick.”

“That’s right,” said Rice.

Olivia and her twin brother, Logan, are the norm at Rice’s practice in terms of vaccine compliance. Still, he’s not surprised that measles is having such a resurgence.

“Travel is the key,” said Rice, who has been a pediatrician for 24 years and currently practices in the Fogelsville office of Lehigh Valley Physicians Group-Pediatrics. “If you’re not vaccinated, and you go to a place like Israel or the Ukraine or even Greece, where there are outbreaks, and you’re exposed to the measles virus, then you return home to a community of people who aren’t vaccinated, that’s when outbreaks happen.”

It’s these vulnerable communities that make such travel so perilous. Already this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says, the number of cases of measles in the United States has reached a 27-year-high, eclipsing the 963 cases reported for all of 1992.

Yet back in 2000, the disease was officially declared eradicated in this country. Why are there so many unvaccinated kids in the U.S. now?

There are lot of reasons why children don’t get immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, Rice said, but the main culprits are misinformation and fear. Much of that, he said, stems from a 20-year-old study that falsely claimed the measles vaccine caused autism. That study was debunked; there is zero connection.

“But once that’s out there, or you do a Google search and the first couple of things that come up are problems with vaccinations, it instills a seed of fear in parents,” Rice said. “Parents want to do what’s right for their kids. But the problem is, they know someone who says, ‘Oh no, it’s scary what can happen after vaccines,’ and ‘My child had this…’ and the fear is multiplied.”

Ironically, part of the reason diseases like measles are on the rise is because the vaccines that prevent them have been so effective.

Personal experience

Tibisay Villalobos-Fry had measles as a teenager growing up in her native Venezuela. As a student, she learned just how scary the disease can be.

“During medical school, I saw kids dying from complications from measles,” said Villalobos-Fry, who is a pediatric infectious-diseases specialist at Lehigh Valley Reilly Children’s Hospital in Allentown. “I saw kids with neurological permanent sequelae [complications to the central nervous system] after having measles infections. So I can relate to what the disease can do.”

But she understands why many vaccine-hesitant parents can’t relate — and not just to measles, but to other preventable diseases, such as pertussis (also called whooping cough), polio, and bacterial meningitis.

“Vaccines were so good for so long, people forgot about those diseases,” Villalobos-Fry said. “They don’t know anyone who has a child who has died of a vaccine-preventable disease because it rarely happens in this country anymore. But they all know somebody who has a kid who has autism. So there is the perception of the problem. It’s easier to relate to something that you see.”

Villalobos-Fry said vaccine-hesitant parents are usually well-educated people who want the best for their kids. But, she said, misinformation has led them to believe there is something intrinsically wrong with how vaccines are made, and they don’t trust the pharmaceutical companies.

They also worry that too many vaccines at a young age will overwhelm their child’s immune system, she said. But the timing of those shots is crucial. They must be given when kids are most susceptible to specific diseases.

“Parents will ask me, ‘Well, why do we need to get the pertussis vaccine?’ and I’ll say, ‘Because younger children die of pertussis if they get it when they’re infants.’ And that is important, and when we see a child on a ventilator with pertussis, I think we have failed our children as a health system because we have failed to provide protection.”

She said parents need to be better educated about the importance, timing, and dosage of vaccines. And she believes anyone who works with kids, in any capacity, should be able to explain these things clearly — especially the medical community.

“A lot of our [medical] residents have never seen any of these diseases,” she said. “So if you’ve never had chickenpox, how can you tell parents about the chickenpox vaccine? When they ask, ‘What are the side effects of the chickenpox vaccine?’ or ‘What is the risk of having polio from the vaccine or polio from the natural disease’ or ‘How many kids who get the MMR [measles, mumps, rubella vaccine] get complications?’ A lot of our bright, young physicians aren’t well equipped to answer these questions because they’ve never encountered [these diseases]. I think we can do better in training our young doctors to be confident.”

Such confidence will help doctors better address parents’ fears, doubts, and concerns, she said. And it will help them have conversations, rather than give lectures, so they can fully address questions like: Why this vaccine? Why now? Why this dosage? What are the potential side effects?

Villalobos-Fry said if she can have that kind of conversation with parents, “I can probably turn around nine out of 10 families who don’t want to vaccinate.”

Talk turns to trust

Kim Pile never questioned her decision to vaccinate her 4-year-old twins Logan and Olivia. She’s had those trust-building conversations with Rice.

“All he wants to do is protect kids,” Pile said. “And if a doctor can give me his advice on what’s going on with vaccines, then I can understand that he’s part of my family and wants the best for my children.”

At his practice, Rice said, talk about vaccines often starts with a baby’s very first visit, or even in the newborn nursery.

“You start fighting the misinformation by normalizing [vaccines] and explaining, ‘This is what we do and why we do it.’ If someone comes in for the first time at age 5 or 6, there’s not that level of trust that has built up since birth,” he said.

That trust is crucial when a parent expresses concern over something he or she has read or heard about vaccines.

“Once you feel like there is a rapport there, you can talk more deeply,” he said. “Like, ‘This is the science, these are the studies and the facts, how does this counter with what you heard?’”

If parents need more convincing, Rice will sometimes share his experiences.

“I’ve seen kids who’ve had just terrible outcomes from measles. I’ve taken care of children who have unfortunately died of pertussis. I’ve taken care of kids who had complications from chickenpox where they were left neurologically devastated, and chickenpox is supposed to be a benign illness, but it’s not all the time.”

He’ll share stories of holding hands with heartbroken parents, and traveling to countries where people beg for vaccines. Because he wants all parents to know just how life-changing vaccines can be.

“It’s OK to be skeptical,” Rice said. “Ask the questions of your pediatrician. But be open to fact-based answers, and know that vaccines are safe and effective. And that we as pediatricians, would never recommend something that would be harmful.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.