Many New Jersey coastal towns not preparing for rising sea levels

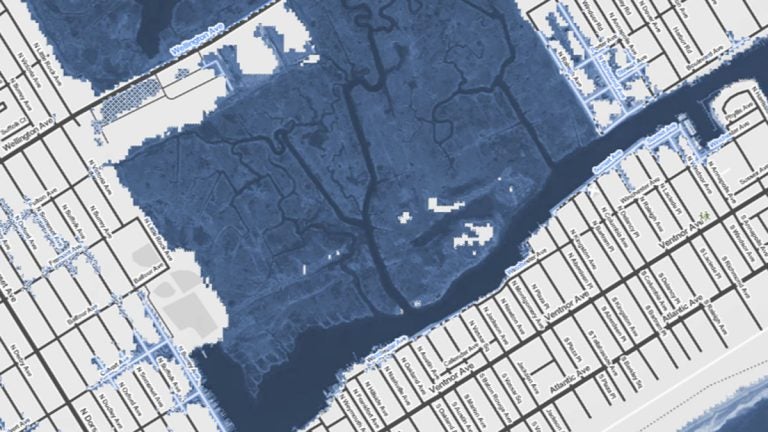

The area in dark blue will likely be underwater by 2100. (Image via Surging Seas map)

On a beautiful fall afternoon a few weeks ago, Anthony Broccoli stood on a nature trail in South Bound Brook, along the banks of the slowly meandering Raritan River. As a professor of atmospheric science at Rutgers, his job is to study long-term changes in New Jersey’s climate and makes computer models of what the weather could be like in the future. That might sound esoteric, but the story of this place, he explained, is a perfect example of why predictions matter.

Just a short distance upstream from where he stood was the Raritan-Millstone Water Treatment Plant, a major source of water for much of Central New Jersey. The plant is located in a vulnerable spot, near the intersection of two rivers. So after it flooded during a tropical storm in the early 1970s, its managers decided to build some extra fortifications.

“They used what was then the estimate of the 500-year flood to determine the height of the berm,” said Broccoli. “However, the concept of a 500-year flood implies that nothing is changing, and that we can look at past records of water levels, and that will tell us what to expect in the future.”

The problem, he said, is that lots of things were changing, including increased development in the area and new weather patterns that brought more frequent, heavy rainstorms. So what seemed like adequate protection back in 1971 was no longer enough three decades later. When Hurricane Floyd hit in 1999, the water level in the Millstone and Raritan Rivers rose so high that it topped the berm and began to flood the plant. The workers had to be evacuated by helicopter, and the plant was closed down for a couple of weeks afterward as a result.

Broccoli explained that basing important planning decisions on experience has historically been a reasonably good assumption, but in a changing climate, that assumption is no longer valid. “Events that may have been very rare in the past could become less rare in the future,” he said. And he thinks it’s a lesson New Jersey would be wise to remember as it goes about rebuilding its coast.

The new high tide mark

Climate models predict more intense storms, and sea levels from Sea Bright to Cape May could rise as much as three-and-a-half feet by the end of the century, compounded by the fact that the Jersey Shore is slowly sinking. So the sort of flooding that took place during Sandy could become much more common.

But while other coastal states are considering weather predictions up to a hundred years in the future in their current planning efforts, New Jersey has so far been more focused on the short-term recovery. Beyond setting baseline regulations, the Christie administration has left many of the planning decisions up to individual municipalities in a nod to the strong tradition of home rule that exists in the Garden State.

Some of those municipalities have been quite forward-looking, and they’ve taken proactive steps to incorporate sea-level rise predictions to ensure their residents will be safer from storms. But overall, it’s been a patchwork approach, without the sort of coordination and leadership from Trenton that many planners and environmentalists would like. They’re worried that amid the rush to rebuild, not enough attention is being paid to long-term resiliency.

Sounding the alarm

Among those concerned is Chris Sturm, senior policy analyst at New Jersey Future, a Trenton-based planning advocacy group. “The state’s done a great job of focusing on rebuilding after Sandy,” she said. “What we haven’t seen enough of is a comprehensive look at a strategy for making New Jersey ‘smarter than the storm’ going forward.” As the state continues its recovery process, she thinks climate change needs to be more central to the discussion.

Sturm thinks it was understandable that long-term planning wasn’t on most people’s radars in the immediate aftermath of the storm. “They didn’t have the capacity. They were responding to a true emergency,” she said. “But I think we’re past that point now. And we see other states stepping forward, engaging in planning and figuring out how to prioritize limited funding to make sure we’re getting the biggest bang for our buck.” Compared to its neighbors in the region, she fears New Jersey has fallen behind the pack.

New York

New York, for example, produced a planning toolkit in the aftermath of Sandy, assessing the state’s risks based on climate projections over the next hundred years. “Governor [Cuomo] very early on convened a commission that looked at these issues and conducted some analysis to make predictions about where the flooding would be and where the sea levels would cause the most trouble,” explained Seth Diamond, director of New York’s Office of Storm Recovery. “And so that has informed a whole host of decisions about what projects we should be looking at to fund, what steps we should be taking with homeowners to make sure that they are protecting their homes.”

Connecticut

In Connecticut, Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Commissioner Dan Esty said concerns about climate change have drawn near-unanimous, bipartisan support. “The experience from Sandy led to a big, coastal legislative bill that went through our general assembly last spring,” he said. “And that provided a whole series of changes in terms of planning processes, setback requirements and sea-level rise expectations that are now embedded in our planning process.”

Maryland

Zoë Johnson runs the Climate Change Policy Program with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. She said lawmakers there have long been concerned about the future. Shortly after Sandy, Governor O’Malley issued an executive order requiring that the state factor the impact of sea-level rise and coastal flooding into any new infrastructure investments.

Delaware

And Delaware has a Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Committee that’s completed a detailed assessment of the state’s risks. “We adopted a guidance policy looking at sea level rise scenarios between half a meter and a meter and a half by 2100,” explained Collin O’Mara, Delaware’s Secretary of Environment and Energy. “So if an asset’s going to be around for a hundred years, we should be planning for the worst-case scenario by trying to make sure that that’s built into all of our infrastructure decisions.”

O’Mara spoke by cell phone on his way home from chairing a meeting of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Eight other states from throughout the northeast took part in that meeting, but New Jersey was not among them. Gov. Chris Christie withdrew in 2011, calling the cap-and-trade program “gimmicky” and “a failure.”

New Jersey

As for how New Jersey is responding to the threats of climate change and rising sea levels in the aftermath of Sandy, a spokesman at the state’s Department of Environmental Protection referred all inquiries to the governor’s press office, which did not respond to several requests to speak with either DEP Commissioner Bob Martin or a representative of the Governor’s Office of Recovery and Rebuilding.

In the past, however, Christie has said the state is taking all sorts of measures to make itself more resilient to future storms. “The fact is that we’re not putting things back the way they were before,” he said in July, while announcing buyouts of Sandy-flooded homes in South River. “We’re making them stronger, either by moving people out of neighborhoods like this or by building dune systems up and down the entire 127 mile coastline to make sure that if another storm like this comes, we don’t have the kind of devastating results we had now.” Christie has also noted that the state is giving grants to help people elevate their homes, assist local communities in their planning efforts, and help harden critical infrastructure like the power grid.

New Jersey Future’s Sturm says she’s excited about the size of the buyout program — some $300 million in all to acquire 1,000 flood-prone homes statewide, plus 300 in the Passaic River Basin. She acknowledges that the state’s adoption of the new FEMA flood maps and the requirement that people rebuilding along the coast raise their homes one foot above the FEMA elevations will provide a bit of added safety in the short term. And she thinks state grants to help municipalities hire planners are a step in the right direction.

Preparing N.J. for rising waters

She doesn’t think those sorts of measures go far enough, though. While much of the focus to date has been on making the state safer from the next storm, Sturm is more worried about what could happen in the decades to come.

“What we’re looking for is a more comprehensive analysis of our risks and state guidance on exactly the risks we face,” she said. “How much do we expect sea level to rise? What is that going to do to storm surge in ten years? Fifty years? A hundred years? Where are the properties that have been damaged two, three, four times before? That kind of information can help us prioritize how we act and where we spend our money.”

The fear is that while homeowners might spend tens of thousands of dollars to elevate their house to bring themselves into compliance with the new FEMA flood maps, those maps are based on current conditions, and do not take sea-level rise projections into account. Given that the average life expectancy of a house is one hundred years or more, homeowners who are simply raising their structures to the minimum required height might have to go through the trouble and expense of elevating them again in a few decades, if sea levels continue to rise.

One solution, say environmentalists, would be for New Jersey to enact stricter, more forward-looking construction regulations like New York and Massachusetts, which require that homeowners rebuilding in flood-prone areas elevate two feet above the heights listed on the FEMA maps instead of just one. On a local level, nearly a dozen towns statewide have so far adopted such rules, while Tuckerton and Monmouth Beach now mandate that residents and business owners elevate three feet above the FEMA requirements.

For elected officials, it can be a difficult balancing act trying to help people repair their damages quickly and cost-effectively while also preventing them from making mistakes that could come back to haunt them in the long term. But the good news is that a study commissioned by FEMA several years ago found that those planning on elevating might as well go as high as possible, since the incremental cost of adding a few extra feet isn’t all that great. Plus, residents and towns that go above and beyond the FEMA height requirements could save substantial amounts on their flood insurance.

Whenever he speaks about the Sandy recovery, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shaun Donovan often quotes a study from the National Institute of Building Science that found that every dollar spent on mitigation today could save four dollars over the long run. Perhaps with that study in mind, HUD’s recent allocation of an additional $5 billion in federal Sandy aid — including $1.46 billion for New Jersey — requires that recipients prepare detailed risk assessments of sea-level rise and climate-change impacts. The details remain to be seen, but environmental and planning groups are optimistic this could compel the Christie administration into making greater strides to confront the risks that lie ahead.

______________________________________________

Below is an interactive map created by Climate Central that allows you to see how rising sea levels could affect your area. Keep in mind that powerful storms can raise the water level be several feet.

Scott Gurian is the Sandy Recovery Writer for NJ Spotlight, an independent online news service on issues critical to New Jersey, which makes its in-depth reporting available to NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.