Hanging on the telephone: Maguire Museum tracks America’s disappearing payphones

The cell phone may have killed the payphone, but photographer Eric Kunsman seeks out people for whom payphones are a lifeline.

Listen 2:43

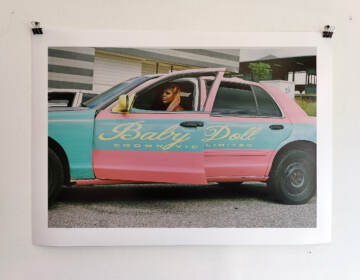

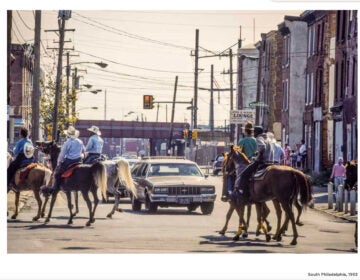

A photographic exhibit at the Maguire Museum at Saint Joseph's University focuses on the payphone as a way of illustrating how a technological divide has left behind many people living in poverty and rural areas. ''Life-Lines Throughout the United States,'' by Eric Kunsman is on view through April 5. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

There are about 35 currently operable payphones in Philadelphia, according to online maps assembled by enthusiasts of the obsolescing technology.

One of them is at Les and Doreen’s Happy Tap, a longtime neighborhood bar in Fishtown whose phone line is wired to the payphone. If you call bartender Shannon Bosak, for example, the payphone rings.

It’s a kind of novelty.

“A lot of the younger kids that come in – adults, of course, but they’re kids to me – they take pictures with it,” she said. “Some of them have never seen one.”

Bosak said nobody ever makes outgoing calls on the payphone, except for one mysterious stranger who comes in a few times a week just to use the payphone. He does not order anything, and nobody at the bar seems to know who he is.

“We try to listen to his conversation because we want to know why he’s using it,” Bosak said. “I put a little thing out that he’s got a hit out on his wife. Doesn’t want any phone traces.”

Bosak is joking, of course. It’s a funny thing to talk about at the bar. But there may be some truth to it: Eric Kunsman believes there is a perception of crime surrounding payphones, particularly outdoor phones in urban spaces. The Rochester, NY-based photographer says payphones can act as social markers, creating the look of a troubled neighborhood.

“How do you get a feeling about a neighborhood you’re driving through, where people roll up their windows and lock their doors,” Kunsman said. “My take on it, from my neighborhood, was the abundance of payphones.”

Kunsman is talking about the Rochester neighborhoods of Charles House and Susan B. Anthony, just west of downtown, where several years ago, he bought a building for his printing business. It’s a lower-income area with a household average of about $21,000, and he noticed a lot of payphones.

“I was ignorant that people were still using the pay phones,” he said. “I just saw them as being archaic.”

Kunsman, originally from Bethlehem, Pa., has spent years on an ongoing photo documentary project, marrying large-format portraits of payphones, overlaying census data maps depicting where they are, and interviews with the people who use them. The exhibition, “Life-Lines Throughout the U.S.,” is currently on view at the Maguire Art Museum at St. Joseph’s University in Lower Merion.

The exhibition shows that locations with payphones are mostly aligned with low-income and immigrant communities, less so with crime. The Maguire gallery has actual payphones visitors can use to listen to pre-recorded interviews with people who use payphones as their primary form of communication.

One of those voices identifies as Carlos, who moved from Puerto Rico to Webster in upstate New York. He washes dishes for $9 an hour and lives with several people in an apartment.

“I don’t have a cell phone because my last one broke, and I haven’t been able to afford a new throwaway phone,” he says in the recording. “Honestly, I don’t call many people. I prioritize other things I need: food and other things I want.”

Carlos uses a payphone outside a nearby gas station to call his parents in Puerto Rico. In the winter, when it’s too cold to stand outside, he keeps those conversations very short.

“Everyone else that matters to me, I live with,” he said.

Carlos said people stare at him while he is using the phone. That is the most common complaint from all the people Kunsman has spoken with at pay phones: people look at you funny.

“You hear over and over: they hate how people look at them, like they’re doing something wrong,” Kunsman said. “We expect now everybody should have a cell phone. So anybody that’s using a pay phone must be doing something wrong.”

The “Life-Lines” exhibition features dozens of large-format photographs of pay phones across the country. There are phones in urban settings covered with graffiti tags or obscured by overgrown landscaping. There are phones next to signs advertising the price of cigarettes and behind sidewalk barbecues and stacked trash cans.

There are also images of rural places where cell phone signals are weak or nonexistent: a lookout point over Muir Woods in Northern California, and a convenience store in the high desert of Arizona seen from a wide view so you can see geographic buttes in the background and a sky streaked with wispy cirrus clouds. The environment is striking: if the image wasn’t in an exhibition about payphones, the viewer might miss the fact that there’s a phone fixed to the outside wall.

“I call them environmental portraits of payphones,” Kunsman said.

When Kunsman started this project, originally called “Felicific Calculus,” Rochester had 1,455 public pay phones, according to data provided in 2018 by the phone and internet service company Frontier. Since then Frontier has pulled out of the pay phone business nationwide. There are currently no working pay phones in Rochester, according to Kunsman.

In Pennsylvania, Frontier is the primary telephone and internet service provider in parts of Chester and Lancaster counties. It is currently being investigated by the state offices of Consumer Advocate and Small Business Advocate regarding customer complaints.

Most of the phones depicted in the exhibition do not work. Some are missing handsets. Some have a phone number printed in the wall text, but calling that number often does not result in a ring.

Kunsman said he was in Tucson, AZ, where a community of people experiencing homelessness set up an encampment around a public phone, only to have it cut off two weeks later. In Philadelphia, he took a picture of a phone at a Sunoco gas station on West Girard Avenue that had a sign taped to it reading “This Payphone Works.” It didn’t. While shooting the phone, several people approached Kunsman and asked if he knew where the nearest working phone was.

There are nascent efforts in some American cities to install free public phones, largely by leveraging technical hacks in existing phone and internet services, a.k.a. “phreaking.” In Philadelphia, the PhilTel project attracted national attention for its plan to create a network of free phones linked through an internet service. So far, it has installed a single phone in a bookstore in Fitler Square.

Kunsman has turned his art and documentary project into advocacy: he is part of an effort to install free phones with free voicemail around Rochester, intended for people without cell phones or who are housing insecure to retrieve messages. He said the first phones should begin appearing in about five months.

At Maguire Art Museum, interim director Jeanne Bracy said the “Life Lines” exhibition is attracting academic attention across the St. Joseph’s campus. Various classes, ranging from art and sociology to business, plan on using the exhibition in their instruction.

“Life-Lines Across the U.S.” is asking the public to submit photos of area payphones to a Google form, which will be mapped on a wall of the gallery. The exhibition will be on view until April 5.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.