Lost letters shed light on Lukens steel from Coatesville, Pa.

A trove of historic letters has been discovered in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, inside the walls of the home of one of the most powerful woman industrialists of the 19th century.

Rebecca Lukens was born into the iron industry in 1794. Her father, Isaac Pennock, founded an iron forge in Coatesville. When Rebecca married a Philadelphia physician named Dr. Charles Lukens, he took over the business — called Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory — upon Pennock’s death.

After her husband died, Rebecca took over the business for herself. She was 30 years old, in charge of a new baby and a dying business.

“I say Rebecca was like George Washington at Valley Forge,” said historian Eugene DiOrio. “She had a huge number of problems. Here she is a woman running a mill. There was opposition from her family. Her own mother was very upset — it’s not appropriate for a woman to run a steel mill. There were financial problems, physical problems with the plant. She stayed with it. There was a lot of competition, and she held on. She’s a major figure.”

Lukens turned the business around with the help of her brother-in-law, Solomon Lukens, who acted as plant manager. As her children grew up they established grand houses on the property for their families, but Rebecca Lukens, a devout Quaker, lived in a humble farmhouse.

That house is now being restored to be included in the National Iron and Steel Heritage Museum, which already uses several buildings on the original steel mill compound. While stripping the houses to the studs, Wesley Sessa of 18th Century Restorations discovered a cache of letters in an unknown gap between two adjacent walls.

The way the walls were built, on studs nailed to the attic joists, created a gap of about an inch and a half. It is believed a box of letters stored in the attic deteriorated, allowing the letters to fall through the gap.

Other letters were brought into the wall by rats and mice, using the paper as nesting material. A mummified rodent was also found in the gap.

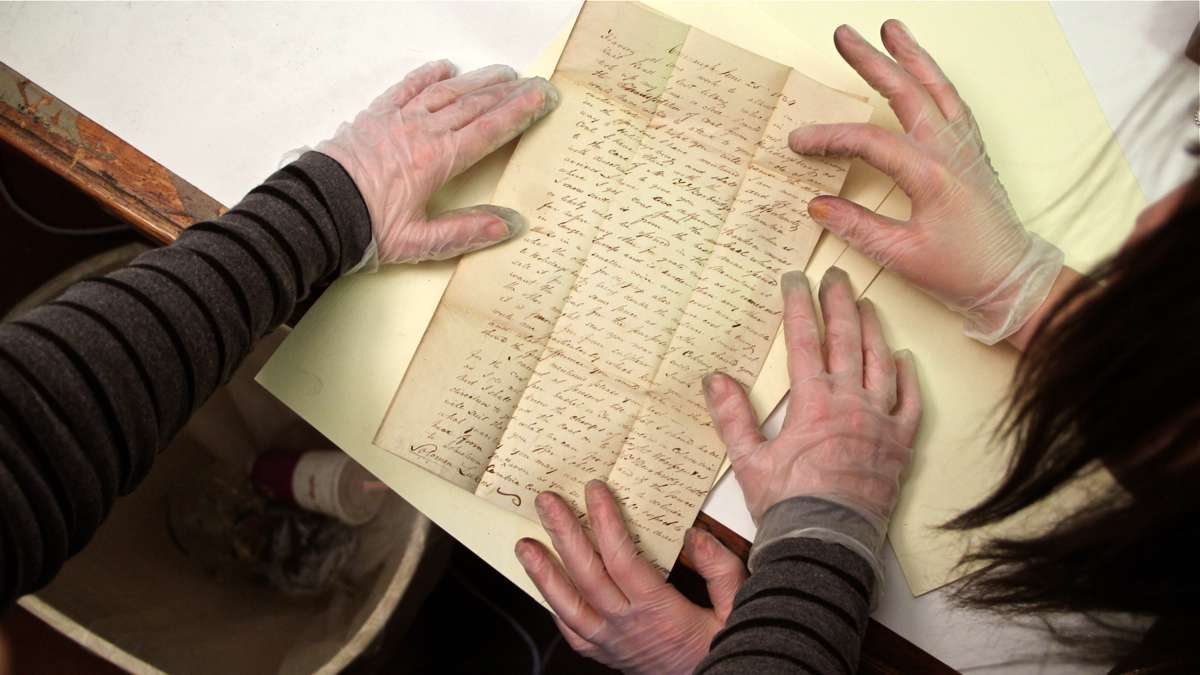

Last Friday, the letters were opened for the first time in 180 years.

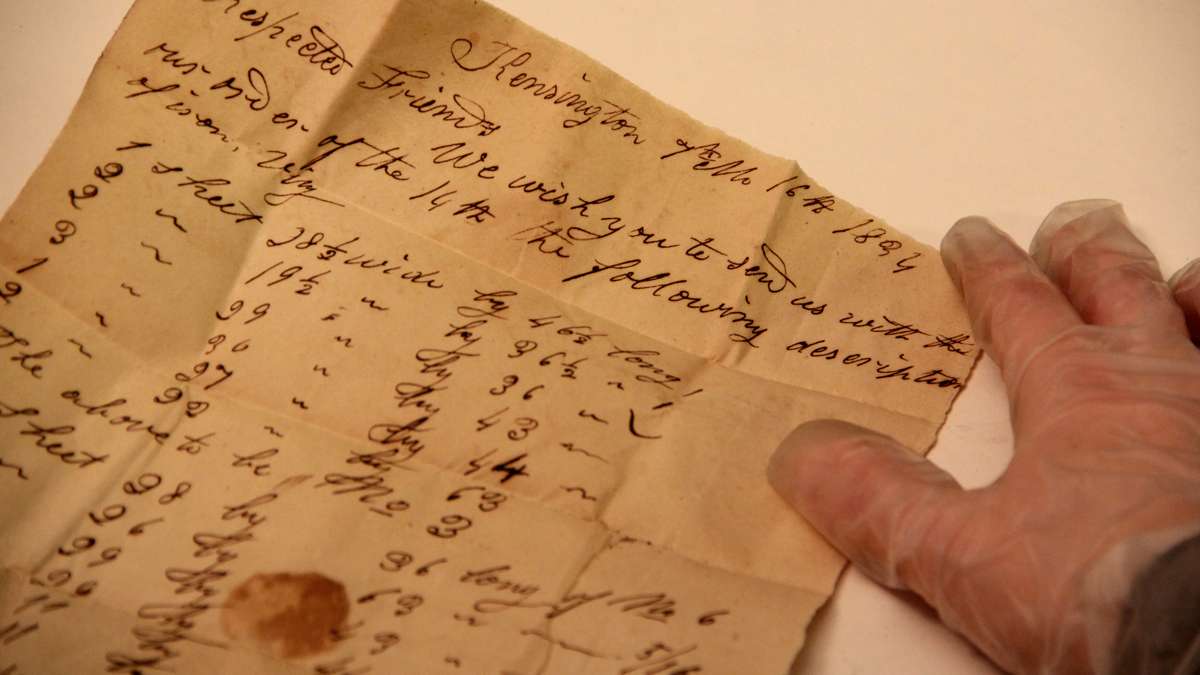

“We’re finding orders for iron plate and boilerplate,” said Kathleen Bratton, collections manager at the museum. “We saw an agent, the secondary party, in Albany, New York, ordering plate in Albany. A sales agent for Lukens in Albany. I never thought of it being that far-reaching.”

Bratton spent a day with conservators at Winterthur Museum in Delaware to learn how to handle fragile paper. The letters were coated in a layer of dirt (and, likely, coal dust from the steel mill) which probably helped to preserve the letters. All are dated 1834, and were sent to the Lukens as business correspondents. Clients and salesmen sent orders, payments, invoices, and requests for speedier service.

The excitement for Bratton is prying open the folded paper to get a glimpse at how the business was run almost two centuries ago. She immediately read the letters aloud to her team around her, trying to decipher the faded ink.

“Dear Mister Solomon Lukens: I request the favor of you to forward to me either by the turnpike, to my own house, or by one the cars along the railroad, to be put out near the store, 3 kegs or 300 pounds, sixpence…something…nails, and 2 kegs of twenty penny, as soon as possible,” said Bratton, stumbling over the faded ink, smudged by rat urine in some places. “Respectfully yours, Mr. Samuel Houston.”

There is very little in the letters — some of which are still too fragile to open — revealing anything personal about the Lukens, but the dry, business language is exciting to historians of the Pennsylvania iron trade. If they can tie the company to certain building projects, in particular infrastructure, major buildings, or shipbuilding, historians can prove that Lukens iron was used to literally build the Industrial Age.

“The Monitor is the classic case. There has always been this question: did Lukens provide iron to the Monitor?” said DiOrio, formerly the president of the Greystone Society, which created the Iron and Steel Museum.

“The Monitor was a Civil War iron-clad ship, considered the turning point of wood-to-iron vessel in the Civil War,” said DiOrio. “We know we sold iron to a firm in New York who in turn sold iron to the shipbuilding company who made the Monitor. But they bought iron from other people as well. So we’ve never been able to tie that down, proof-positive.”

So far, the letters do not show anything related to the Monitor, but with more research it could tie Lukens to other major projects of the era. In the immediate future, the letters will be opened, photographed, and re-sealed until money can be found for professional conservators to have a go at them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.