Look again: Phila Art Museum and Whitney double up on Jasper Johns

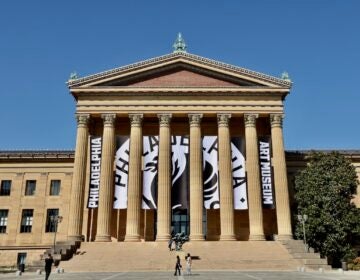

The Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum in New York collaborate on the largest exhibition of the iconic American artist.

A lifetime retrospective of the work of Jasper Johns, organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, is being presented simultaneously at both institutions. Visitors who attend the exhibition at one venue will get half-price admission to the other. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Embedded in the ceiling of the entrance foyer of Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is an audio speaker from which plays a series of declarations written by Johns.

The voice is not Johns’. His close friend, composer John Cage, had recorded himself reading selections of Johns’ writings in 1986:

“One wants from a painting a sense of love. The final suggestion, the final statement has to be not a deliberate statement, but a helpless statement. It has to be what you can’t avoid saying.”

“In my early work I tried to hide my personality and my psychological state, my emotions. This is partly due to my feelings about myself, and partly due to my feelings about painting at the time. I sort of stuck to my guns for a while but eventually it seemed like a losing battle.”

A towering figure of 20th century American art, Johns has always been a quiet artist, hesitant to talk about his work and rarely offering anything like an explanation of what he has been steadily making for seven decades. The work itself is meant to stand on its own. So it may not seem unusual that the first thing visitors encounter at the largest and most comprehensive exhibition of his work, is somebody else’s voice.

Mind/Mirror, running from Sept. 29 to Feb. 13, features about 500 works spread across both the PMA and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, each exhibition mirroring the other. The co-curators say the structure of the collaborative show mimics Jasper’s lifelong body of work.

“The show is large and one could focus on the complexity that it took it to put together, but the basic idea is very simple,” said PMA curator Carlos Basualdo. “Can we do a show that, by its very structure, tells you something about the way in which Jasper Johns thinks about his work?”

The complexities are significant. Each exhibition at the two museums was put together as a unique curatorial vision, while intentionally mirroring one another. The PMA’s show is set up in a series of 10 rooms, each describing an aspect of John’s work. The Whitney also has 10 rooms, each corresponding with themes in the Philadelphia rooms.

So, a PMA gallery full of John’s paintings of numbers, a motif he worked many times over decades, mirrors a room at the Whitney filled with work featuring other motifs Johns worked over and over again: maps and targets.

A Philadelphia room about John’s fascination with and collaborations in Japan is thematically tied to a New York room about John’s relationship with South Carolina, where he grew up. The “Nightmares” room in Philadelphia filled with dark paintings associated with anxious emotions — some likely made in response to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s — corresponds with a brighter “Dreams” room at the Whitney.

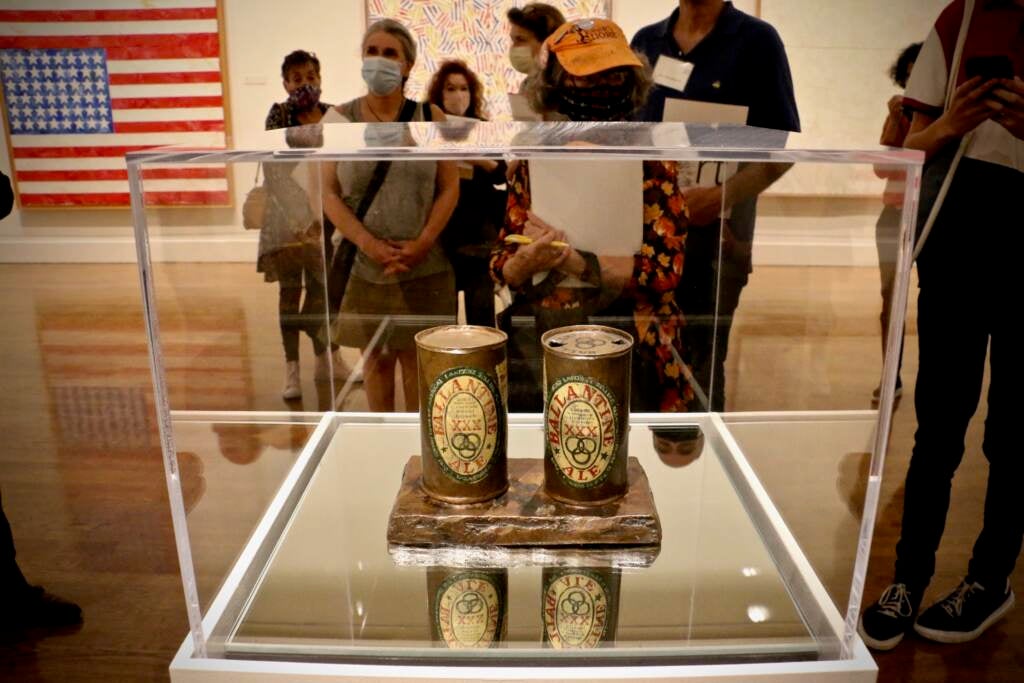

The concept of mirroring the two exhibitions evokes Johns’ work. He has regularly used doubles and variations in his work, across multiple canvases.

“There’s a whole variety of ways in which Jasper uses mirroring and duplication and repetition in the work,” said Basualdo. “You see many works that are versions of an earlier work with slight variations and in different mediums. You also see works in which they’re very structured, a duplicate of a certain image twice.”

“Ale Cans” (1964) at the PMA, for example, is a painted bronze sculpture of two cans of Ballantine beer. They seem to be identical, but on closer inspection one is hollow, having been opened with a beer can punch, the other is solid bronze with an unopened top. Nearby is John’s painting of two American flags, one stacked on top of the other, together comprising a single work.

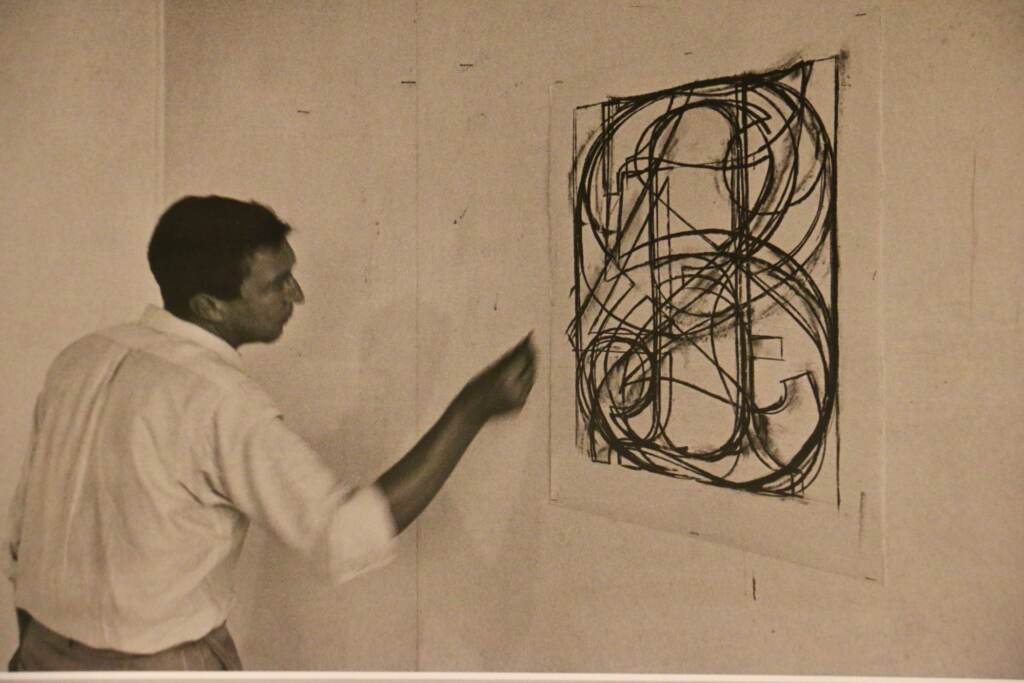

Johns extended the concept of duality beyond his canvas frames. Basualdo recreated a 1960 exhibition at the gallery of Leo Castelli in Manhattan, the first dealer to give him a solo show. The original exhibition had eight canvases of abstract work, all of them independent works that are also related to each other: only together do they complete Johns’ unified vision.

Those paintings ultimately do not live together. They were sold and separated. Basualdo was able to wrangle six of the original eight canvases back together for this exhibition, to give a nearly-complete sense of what the artist intended.

Similarly, the Whitney recreated a solo exhibition at the Castelli gallery, from 1968.

Earlier reporting about Mind/Mirror by The New York Times suggested the extensive collaboration between the PMA and Whitney may have been complicated by disagreements between the two institutions: Basualdo’s vision was that visitors would ultimately see both exhibitions to fully appreciate the mirroring effect, while that of Whitney curator Scott Rothkopf assumed that, realistically, most people will only attend one of the shows, and that one will likely be the Whitney’s.

If there had been disagreements, they did not show at the PMA preview on Wednesday, which came off as an affectionate, post-pandemic huddle (the show was originally intended to launch last year, but for the pandemic). Bssualdo and Rothkopf stood next to each other and mutually praised one another’s work. Whitney director Adam Weinberg came to Philadelphia and seemed to reference an iconic line from the film Jerry Maquire: You complete me.

“Seeing Philadelphia’s twin exhibition, I now feel complete,” said Weinberg. “It’s as if these are two exhibitions that have been separated at birth, are now rejoined.”

Mind/Mirror encourages conceptual thinking on the part of the viewer, to extend a particular painting’s meaning beyond the picture frame to another picture across the room, or in another exhibition in another city. Basualdo is quick to point out that simply looking loosely at the individual paintings — for example the thick encaustic topography Johns built on the surface of his famous paintings of the American flag — hold rewards.

“It all sounds very abstract and very intellectual, but … he’s an amazing colorist. He’s a very experimental artist in any medium he touches. He has this sense of precision,” said Basualdo. “When you’re in front of one of his subjects, it looks definitive. It looks final in many ways because it’s so beautifully made.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.