If it makes you happy: Constitution Center CEO’s book pursues American happiness

"The Pursuit of Happiness" traces the moral philosophy that drove the Founding Fathers.

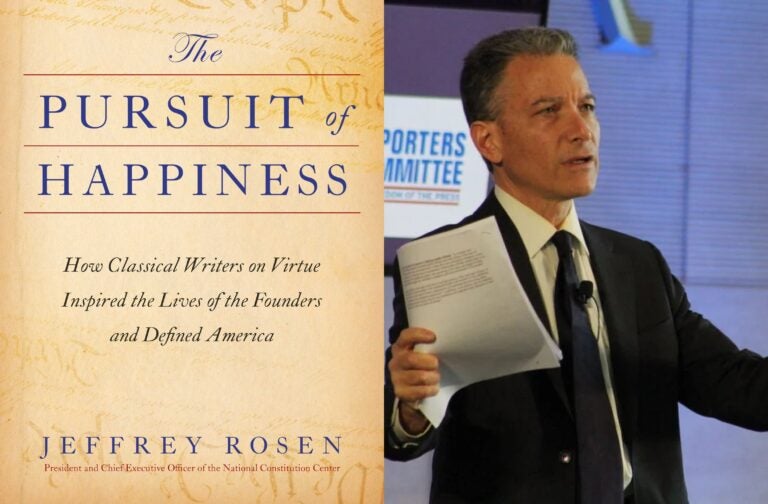

'Pursuit of Happiness' by Jeffrey Rosen. On the right, Rosen at the First Amendment Summit. (Photo of Rosen by Cory Sharber/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

For folks of a certain age, their bedrock understanding of the Declaration of Independence can likely be traced back to watching Saturday morning cartoons.

The series “Schoolhouse Rock!,” with catchy songs and eye-candy animation, explained in the episode “Fireworks” that America’s Founding Fathers proclaimed all men had a right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Animating that last spoken phrase is the image of a man wearing a blue Colonial-era suit laughingly chasing a woman in a red dress across the screen. It happens three times in the episode, a “running” gag whose pun was clearly intended.

But that gleeful pursuit of pleasure, or romantic excitement, is the polar opposite of what the Founding Fathers intended.

“Our current understanding of happiness is feeling good. The pursuit of pleasure. You do you. Let it all hang out. The classical understanding is completely different,” said Jeffrey Rosen, author of the new book “The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America.”

“It is self-mastery, self-reliance, character improvement,” he said. “Using your reason to balance your unreasonable passions or emotions, so you can achieve the calm tranquility necessary for personal growth.”

Rosen is president and CEO of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia and a law professor at George Washington University. Despite his scholarship and deep education — he studied at Harvard, Oxford and Yale — he was surprised to find that he actually had a flimsy understanding of where the authors of the Declaration of Independence derived the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” and what exactly they meant.

It took the pandemic for him to drill down and figure it out. During the COVID shutdown, Rosen took to re-reading the Founding Fathers — a syllabus seldom taught anymore in American universities.

“I was reading Ben Franklin and noted that he had a passage about how virtue is necessary for happiness. A few weeks later I saw that Thomas Jefferson had come up with a similar list of virtues for daily living, and he used the same author and the same book as the core of his understanding of the pursuit of happiness,” Rosen said. “It’s a book by Cicero called ‘The Tusculan Disputations.’”

A towering thinker of ancient Rome, Cicero had retreated to a rural villa in Tusculum, Italy, around 45 B.C. after the death of his daughter to read and think and write about moral philosophy, including the nature of happiness.

“We must keep ourselves free from every disturbing emotion,” Cicero wrote. “Not only from desire and fear, but also from excessive pain and pleasure, and from anger, so that we may enjoy that calm of soul.”

Rosen discovered that both Franklin and Jefferson, independent of one another, revered Cicero’s thought and recommended his writings on virtue to anyone who asked, along with other moral philosophers such as Hume, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius and John Locke.

“I remember yearning for this kind of guidance in college. I went to college in the ‘80s. It was the ‘greed is good’ decade, and I was looking for an alternative to materialism and hedonism and pop culture,” he said. “I was totally unconvinced by Puritan theology, looking for an approach to how to lead a good life by reason rather than revelation.

“What I didn’t realize was all these books had fallen out of the curriculum,” he said. “This is exactly the question that the Greek and Roman moral philosophers set out to answer.”

It being the Age of Reason, Franklin and Jefferson set about inventing systems by which that “calm of soul” might be attained. Again independent of one another, they both devised similar 12-point checklists against which they would rate themselves daily. Franklin’s included order, temperance, humility, industry, frugality, sincerity, resolution, moderation, tranquility, cleanliness, justice and silence.

Every day, Franklin would put a mark next to any quality that he felt he did not adequately express. Daunted by the excessive number of marks, he soon abandoned the project.

However, the list gave Rosen a structure for his book: Each of the 12 chapters is named after one of those qualities, describing how prominent people of early American history — from Washington to Lincoln — aspired to them.

A funny thing happened on the way to happiness: Rosen took notes on those philosophical treatises that informed the Founding Fathers. Those notes spontaneously took poetic form.

Rosen found himself writing sonnets in response to, for example, Plato’s “Phaedrus.”

Our souls are forged of three-part composite

A charioteer and pair of winged steeds

One horse is noble temper’s reposit

That other, seeking pleasure, passion leads.

“It was a very unusual practice, to say the least. You could call it weird,” he said. “I would read from the wisdom, watch the sunrise, and then just felt moved to sum up the essence of what I’d read in these sonnets.”

Rosen had fully immersed himself into the mindset of early American thinking. The Black poet Phillis Wheatley, the statesman Alexander Hamilton and the poet and independence activist Mercy Otis Warren all notated their reading with poetry.

“[President] John Quincy Adams would wake up in the White House, read Cicero in the original, write sonnets, then walk along the Potomac to watch the sunrise,” Rosen said. “There’s something about this wisdom that is so balanced and beautiful, you just want to distill it as well as you can.”

“The Pursuit of Happiness” offers a deeply personal perspective on the people building an American nation based on their own moral fiber, and the ideal of happiness.

“We can’t be a more perfect union as a nation unless we find that more perfect union among ourselves,” Rosen said. “It’s that shining faith in the individual which is really at the center of the American idea.”

Rosen is not throwing shade on the oversimplification of moral philosophy seen in “Schoolhouse Rock!,” still one of the best examples of television used as an educational tool.

“I loved ‘Schoolhouse Rock!’ We would love at the NCC to re-bottle that magic,” he said. “But a pop version of Cicero’s ‘Tusculan Disputations’ might be a little less fun.”

On Monday, Feb. 19, Presidents Day, Rosen will be interviewed about “The Pursuit of Happiness” on stage at the National Constitution Center, with Jeffrey Goldberg, editor of The Atlantic. The 6:30 p.m. event is free, but registration is required.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.