It’s complicated: Life and work of Rube Goldberg at Philly’s Jewish Museum

Exhibit on life and work of Rube Goldberg opens at National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

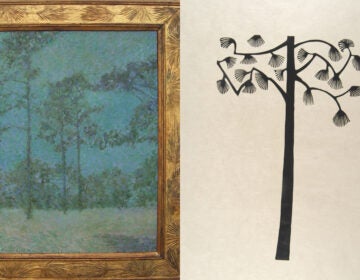

The National Museum of American Jewish History looks at the life of Rube Goldberg. (Courtesy of the National Museum of American Jewish History)

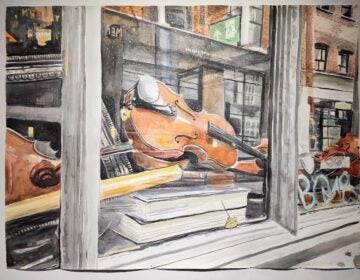

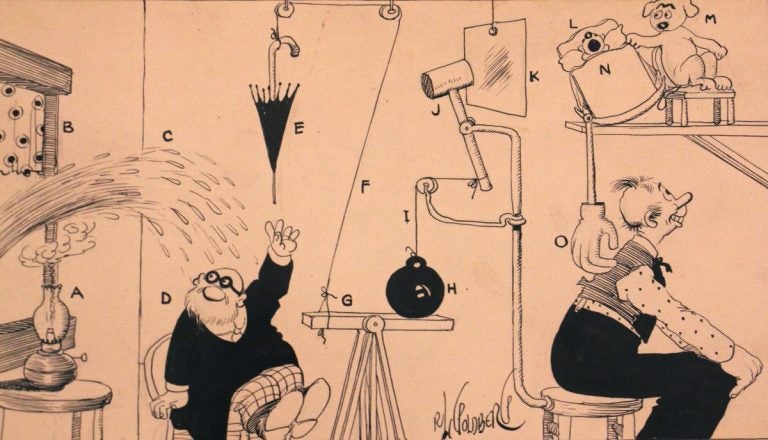

“The Art of Rube Goldberg” exhibition starts – of course – with a contraption. You crank a pencil sharpener, which spins a wheel, which sets loose a ball, which runs down a ramp, which triggers a light switch.

Many of Goldberg’s “inventions” were created by a fictional character, Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, who attempted to accomplish simple tasks using the most complicated means possible.

Despite being nonsense, Goldberg’s inventions have become ingrained in American culture. They’re featured in movies (“Modern Times”), music videos (“This Too Shall Pass” by OK Go), and a board game (Mouse Trap).

He even became part of our language: “Rube Goldberg” appears in the dictionary as an adjective.

Although Goldberg studied to be an engineer, he never made these machines. He designed them to be cartoons.

If you look closely at them – as the exhibition opening Friday at the National Museum of American Jewish History allows – you’ll notice they are not entirely mechanical. Unlike their real-life imitators, the cartoon machines always hinge on animal behavior or a person acting irrationally.

For example, a golfer swings backward, which knocks apples out of a tree, which land on a kettle drum, which the caddie mistakes as thunder, which causes him to bolt and trip over a golf bag, which knocks over a pole, et cetera.

A tailor measuring a client calls out numbers, which his assistant mistakes as a football play, which causes him to tackle a clothes dummy, which knocks a dangling paddle, and so on and so on.

Ideologically, the inventions are anti-machine.

“He said, ‘They are satirical representations of progressive nothing,’ ” said his granddaughter, Jennifer George, who helped put this show together.

George, who handles the Goldberg legacy and oversees the national Rube Goldberg Machine Contest, and said the best machines tell a story about being human.

“I always talk to kids who say, ‘We’re going to build a Rube Goldberg machine!’ and I have to explain the best way to start thinking about building a machine,” she said. “ ‘Who’s the funniest kid in class?’ There’s usually some kid in the back row picking their nose, and they’re all pointing at him. So I’ll say, ‘He’s the one you gotta enlist to make it funny!’ ”

“The Art of Rube Goldberg,” a traveling package exhibition, actually spends relatively little time on his invention cartoons as it relates the sweep of Goldberg’s whole life.

He was born to Jewish immigrants in San Francisco. His father, Max Goldberg, pushed him to study mining engineering at University of California Berkeley. After college, he briefly had a job working in the sewer.

Goldberg showed talent for drawing, but he would not pursue it professionally without his father’s approval.

“Rube didn’t worry about impressing too many people, but all through his life — as I know it — his dad was … you didn’t mess around with that,” said another of Goldberg’s grandchildren, John Ruben George. “Max was always his idol.”

Once he granted permission, Max Goldberg sent his son to New York to make a go as an illustrator — with a diamond in his hand.

“He said, ‘If you ever get in trouble, use the diamond,’” said George. It ended up in the engagement ring Rube gave to his future wife, Irma.

His cartoons thrived on absurdity. His first popular success was “Foolish Questions,” featuring one person asking an inane question (“Watching the scoreboard?” asks one sports fan to anther) and the sarcastic, sometimes surreal response (“No, I’m leaning against the ocean”).

He was one of the first widely syndicated cartoonists, with ongoing strips “Mike and Ike – They Look Alike,” “Boob McNutt,” and those “Foolish Questions.”

Following the success of his invention cartoons, Goldberg made a stab at Hollywood, writing the script for “Soup to Nuts” (1930) for the Three Stooges. He soon went back to New York, but not before befriending Charlie Chaplin, who used Goldberg’s ideas for a now-famous comic routine in “Modern Times” featuring a factory worker’s automated lunch delivery system.

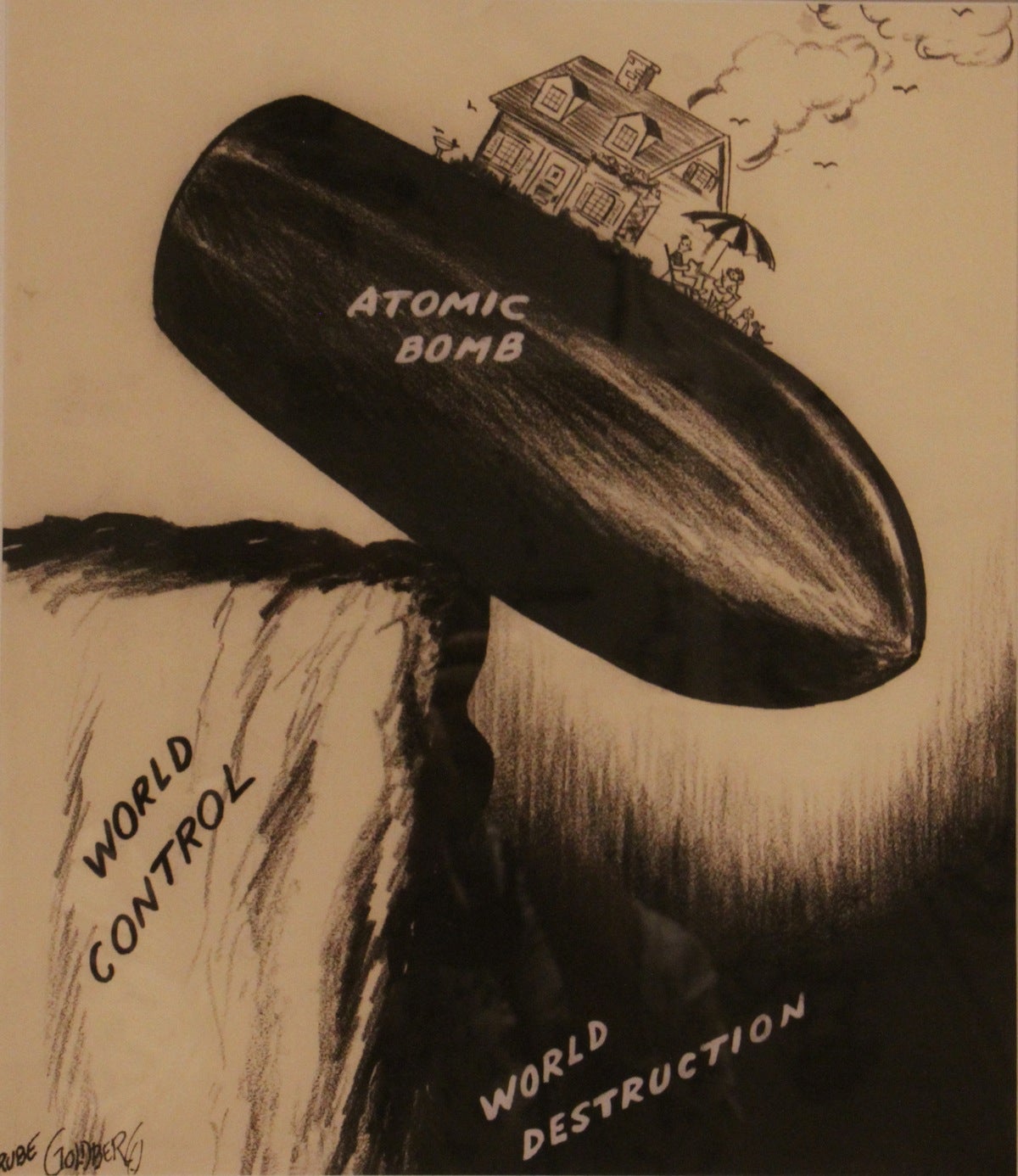

His later career focused on political cartooning in a much different style from the madcap chaos of the inventions. Those cartoons are much simpler, delivering a message as urgent as it was logical. Although he is not widely remembered for that more serious work, it won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1948.

“Cartooning changed,” said John George. “Cartooning became more sophisticated, or whatever. It wasn’t the same humor as it had been in the ’10s, ’20s, ’30s. It changed. So he moved into another use of his talent.”

Nevertheless, to the end, Goldberg was tickled by the absurdity of modern life. In the 1960s, George remembers going with his grandfather to eat at the old Horn & Hardart Automats, where the nickel-operated food dispensaries never failed to give the old man a chuckle.

“If he looked now and saw that I have five remotes on my TV table, he would have a heyday with that,” said George. “There’s nothing new under the sun.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.