In year of labor pains and gains, Philly union members march

One union grew with hundreds of newly organized workers at Philadelphia International Airport, while high court ruling diminished other ranks.

-

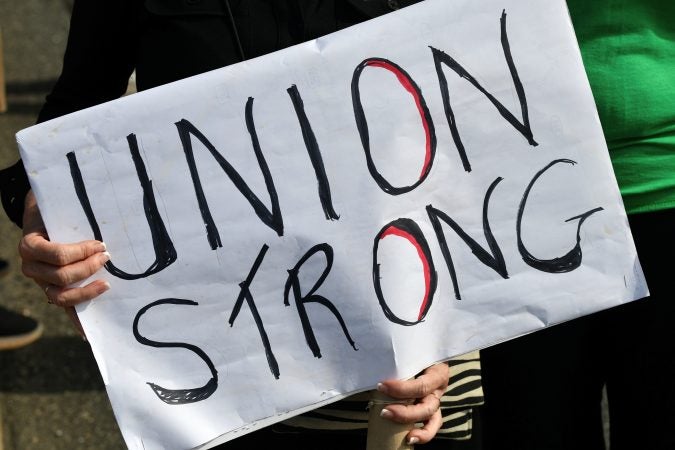

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Mayor Jim Kenney speaks at the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

AFT President Randi Weingarten speaks at the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Governor Tom Wolf speaks at the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Rally ahead of the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Congressman Bob Brady at the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Coiuncilman Bobby Henon and State Rep Martina White at the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

-

Malcolm Kenyatta and Dwight Evans at the annual Labor Day Parade on Columbus Boulevard, on Monday. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

Many hundreds of unionized workers marched in a show of solidarity today in Philadelphia’s Labor Day Parade. But the mix of those marching in South Philly is changing. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling and the changing economy are boosting some unions, while others are dealing with a new reality.

This year represented a major shift for hundreds of workers at the Philadelphia International Airport. The Service Employees International Union was able to organize everyone from those who push wheelchairs to those who work for a contractor cleaning airplanes.

“We’re really doing two things, which seems pretty straightforward, we are talking to low-wage workers — so talking to people who work in airports, the parking industry, security officers … the biggest employers in the United States are primarily low-wage service sector employers,” said Gabriel Morgan, the vice president of SEIU Local 32 BJ, a major force in the organization drive. “Once we decide we are going to dig in and organize an industry based on enough worker support, then we spend the resources to get it done no matter how long it takes.”

Arien Linder, who works at the airport as a wheelchair agent, doesn’t work for the airlines directly. She works for Prime Flight, which contracts with the airlines. Since joining the union, she said her pay has increased. But more importantly, she said, workers are feeling more respect.

“The communication was way off, and the respect level for our rights as workers was way off as well,” Linder said. “But since we got the union, everything — all the improvement that we fought for — has progressed and is progressing each and every day,” Linder said.

SEIU may be adding members and expanding into new areas, but unions representing public employees are dealing with a very different environment.

Ebbing membership

A U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June ended the practice of “fair share” payments, the dues paid to unions from workers covered by union contracts who choose not to join.

Fred Wright of District Council 47 of AFSCME, which represents white-collar city workers in Philadelphia, said the ruling affects quite a few people in his approximately 6,000-member union.

“A loss of approximately 200 agency fee payers who were identified as not wanting to be part of a union,” he said. “But on the upside of this, we had a number of people contacting us, stating they wanted to sign up and join the union.

“I think it’s an opportunity for us to organize people, for people to understand what the union stands for.”

Even though workers who decline union membership no longer have to contribute to the union, Wright said, the union still has to defend them when they are accused of wrongdoing.

“We have an obligation to represent everybody that is part of the collective bargaining agreement … whether they are a member or they aren’t a member,” he said.

Art Hochner, professor emeritus in human resource management at Temple University, also led the faculty union there. At age 70, he still goes to work every day at the union’s office to organize its archives with the intentions of penning a book. If public-sector unions want to grow, he said, they need to go back to their roots — making their pitch directly to workers.

“You’ve got to influence the members to unite and work together to achieve aims that benefit the majority of people,” he said.

In Pennsylvania, the electricians union IBEW is the single largest political contributor, but Hochner said the voices of small unions will shrink in this environment.

“To me, the biggest threat is that if the unions don’t have money to put into politics or do the lobbying and make the effort to influence policy, then big money interests are going to be the ones who do,” he said.

A union serves as a way for low-wage workers to have a united voice to influence how they are treated by the people who do have money and power, he said.

In 2017, union membership nationwide held steady at about 11 percent of the workforce. In its heyday, unions represented one-third of American workers.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.