In South Jersey, a familiar fight to save a historic African-American cemetery

Listen-

Surviving Civil War Veterans are buried at the Mount Peace Cemetery association. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Surviving Civil War Veterans are buried at the Mount Peace Cemetery association. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

The graves of Mount Peace Cemetery stretch back into the woods. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Yolanda Romero is secretary of the Mount Peace Cemetery association. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Surviving Civil War Veterans are buried at the Mount Peace Cemetery association. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

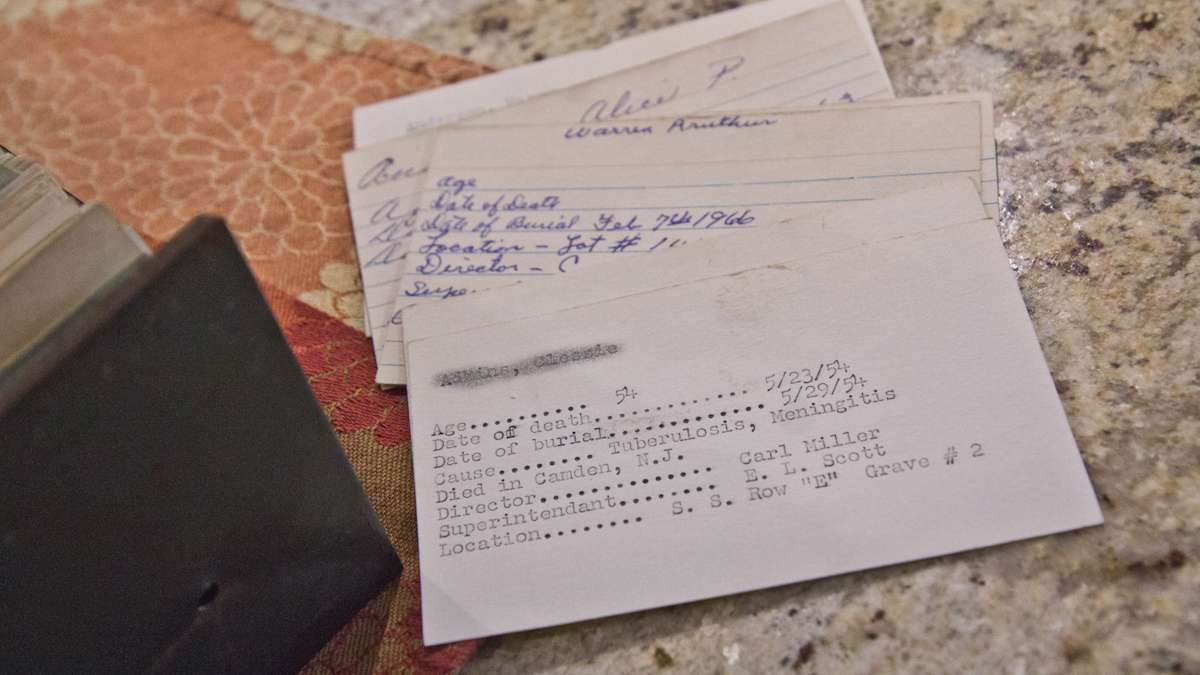

Cemetery records in the possession of Yolanda Romero, secretary of the Mount Peace Cemetery association. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Mary Ann Wardlow is mayor of the mayor of Lawnside Borough, N.J. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

A dedicated tombstone marks the accomplishments of John Lawson, one of the few African American Civil War Veterans to receive the medal of honor. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Yucca plants are planted marking and around graves at Mt. Peace Cemetery in Lawnside, N.J. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Neil Butler maintains his mother’s grave and often volunteers to help upkeep Mt. Peace Cemetery in Lawnside, N.J. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Many cemeteries boast residents whose fame followed them into the afterlife, making their gravesites a point of pilgrimage for those still living.

Mount Peace Cemetery, one of New Jersey’s largest African-American graveyards, has John Lawson.

He was a Civil War hero who earned the military’s highest distinction — the Medal of Honor — after he refused to leave his ship’s post despite getting seriously wounded in a Confederate shelling.

His headstone stands out: It has a clearer inscription and sharper edges than its time-weathered neighbors, after proud veterans, politicians and Lawson’s descendants dedicated a new marker in 2004.

But he’s not buried there.

No one knows where he is.

“We confirmed from the military records that he is indeed buried in the cemetery, but we haven’t found him yet,” said Yolanda Romero, a trustee who oversees the historic, 12-acre cemetery in Camden County’s Lawnside borough. “Maybe someday we’ll find him. Our idea is that he’s probably in the back.”

“The back” is more eerie wilderness than orderly resting grounds. Woods stretch as far as the eye can see, with vines and other overgrowth swallowing tombstones so completely that many have become buried altogether.

A dwindling but passionate group of preservationists has worked hard for decades to restore Mount Peace, which sprawls between White Horse Pike and Interstate 295. But as senior citizens, they’re no match for Mother Nature. Much of the 115-year-old cemetery seems just a few growing seasons away from obscurity.

It’s a common problem for old cemeteries, especially those – like Mount Peace – whose charitable missions have kept their bank accounts light, one industry expert says.

“Cemeteries are unique in that they service what they sell forever. Nobody else does that. You might get a five-year warranty on something, and then the seller is done. But with cemeteries, it is an ongoing obligation to maintain the grounds forever, and that’s a long time,” said Robert M. Fells, executive director of the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association. “Many times, the people who run them are full of good will. They’re not trying to make money out of it themselves, they’re volunteers, their heart is in the right place. But boy, they could use some business advice.”

Mount Peace opened in 1902 as a nonsectarian burial ground for African Americans barred from whites-only cemeteries. By the turn of the century, it had become a resting place for thousands, including former slaves and countless war veterans, at least 77 of whom served in the Civil War.

But bad business definitely helped fuel Mount Peace’s disrepair, because the original owner went bankrupt in 1952. Subsequent managers, to raise money, sold off an 8-acre plot to a gas station. It closed for further burials about 10 years ago, so no new money comes in from plot sales.

Bad luck also played a part. A fire in the 1950s destroyed the cemetery’s plot maps and burial records. By the late 1970s, weeds and trees had consumed several acres, and locals used the cemetery as a dumping ground.

“It was terrible — a real eyesore,” said Lawnside Mayor Mary Ann Wardlow, who has lived in the borough for almost 50 years.

By 1980, volunteers began organizing weekend cleanups and researching veterans’ graves, which they marked with American flags.

Romero’s parents led the effort after they moved to Lawnside from Philadelphia in 1976.

“They had an undertaker friend in Philadelphia, and when he heard where they moved, he said: ‘Oh, you live behind that dump of a cemetery!’ Well, my mother’s nickname was ‘The Duchess,’ and The Duchess was not going to live behind a dump. So she told my father: ‘We have to do something about this!’” Romero said with a laugh.

Cleanup volunteers found everything from an old boat and a broken stove to condoms and used needles in the undergrowth.

But the afterglow from every cleanup was short-lived, as nature relentlessly reclaimed the land.

Mowing has proved to be a surprising, ongoing challenge.

“We broke a lot of lawnmowers in the beginning, not knowing there were stones underneath there (the weeds),” Romero said.

Neil Butler used to do it solo, for free.

“It was a lot of work,” said Butler, 69, whose late mother lies in a tidy, flower-filled, mulched gravesite, one of the prettiest at Mount Peace. “I would weed-whack first, because if you use a lawnmower, you don’t know what you’re gonna hit. That would take one whole day. Then I would come back and cut it with a lawnmower, and that would be another whole day. There were nights I would even come here after work (to landscape).”

Now, an “angel from heaven” has swooped in to help. That’s what Romero calls David Zallie, a cemetery trustee who owns the ShopRite across the street. He pays for landscaping crews to mow the cemetery’s acreage along White Horse Pike.

Still, other problems abound. Old, wooden coffins have decayed, toppling and tilting headstones and leaving behind ground so uneven it undulates like moguls on a ski slope. And flat prickly cactus, often planted to mark the graves of those who couldn’t afford headstones, has long ago spread, leaving some original interment locations a mystery.

Treasure-hunters even unsuccessfully tried to dig up at least one grave.

Police have stepped up patrols, which at least helped cut down dumping and other illicit activities, Wardlow said.

But well-worn trails meander through the cemetery, made by the many passers-by who use the unfenced cemetery as a cut-through.

“That’s the biggest need we have right now – fencing,” Romero said. “That’s tens of thousands of dollars. And then, of course, we need to finish reclaiming the rest of the cemetery. I don’t know what that would cost in today’s dollars.”

The cemetery has a $100,000 maintenance and preservation fund, but state law allows trustees to spend just the interest earned on that principal.

“We used to get $5,000 to $8,000 a year, but the economy has been so bad there’s no money coming in now. Last year, we got like $16 or something,” Romero said. “It’s all just a matter of money. The bottom line is we’re broke.”

She hopes to entice local students – those needing to complete community-service requirements, or those just tender-hearted – to participate in yet more cleanups this spring and summer.

Absent that, Fells suggested that the Mount Peace trustees start getting “creative,” as the trustees at Washington, D.C.’s Congressional Cemetery did a few years ago when poison ivy, English ivy, kudzu, and other invasive plants began taking over.

“They hired themselves a new general manager, a fellow who’s quite creative. He hired a herd of goats to come in, run through the cemetery and eat up all the grass, all the weeds, everything else, and it made the place look a lot better,” Fells said. “This is what people need to do. They need to put on their thinking caps.”

Or maybe just let it go to the dogs. “Cemetery Dogs,” a fee-based dog-walking program, was another unorthodox answer the D.C. cemetery came up with to raise money for maintenance needs.

How to ensure that a century-old cemetery survives another century?

“It really has to be a partnership with the public,” Fells said. “It’s that simple.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.