In Philly’s high school choice system, male and Latino students seem to lose out

Students gather outside Masterman high school in Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY, file)

A new study of Philadelphia’s free-wheeling high school choice system comes to discouraging and familiar conclusions about who has access to the best schools and who doesn’t.

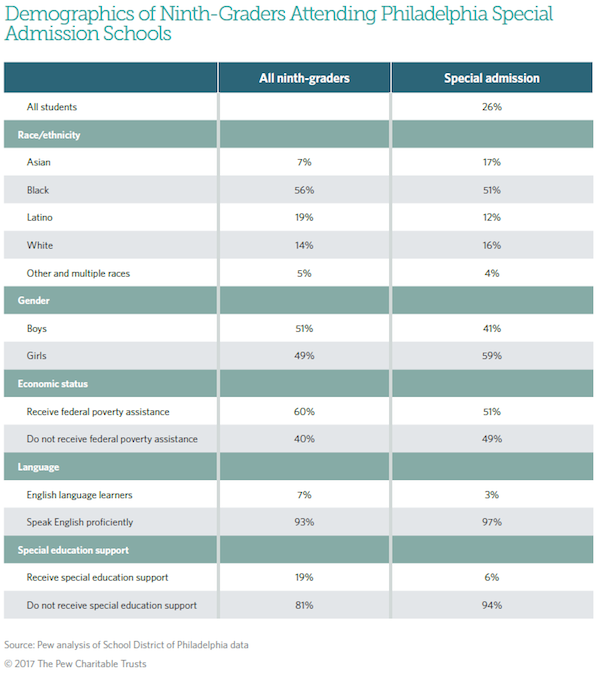

The report, assembled by the Pew Charitable Trusts, found that Asian, and female students are more likely to apply to desirable admissions schools, such as Masterman, Central, and Science Leadership Academy, and that white, Asian, and female students are more likely to be accepted by those schools.

Hispanic and male students, meanwhile, disproportionately enroll at one of the city’s neighborhood high schools, which are long synonymous with poor academics.

The paper, titled “Getting Into High School in Philadelphia: The Workings of a Complicated System,” examined application and acceptance rates at all 166 of the district’s programs for high school students. It featured an especially detailed analysis of the city’s 21 special admissions programs, which have the highest bar to entry and attract the most applications.

White and Asian students were proportionally more likely to attend these highly-selective programs, although that’s not necessarily indicative of bias in the selection process. White and Asian students were also more likely to have the requisite test scores to qualify for admission.

But beyond those self-explanatory correlations, there were some genuine puzzles in the data.

Latino students, for instance, appear to be particularly disadvantaged by the city’s high school choice system, which allows students to apply to any school in the city and gives school administrators ultimate say over who gets admitted.

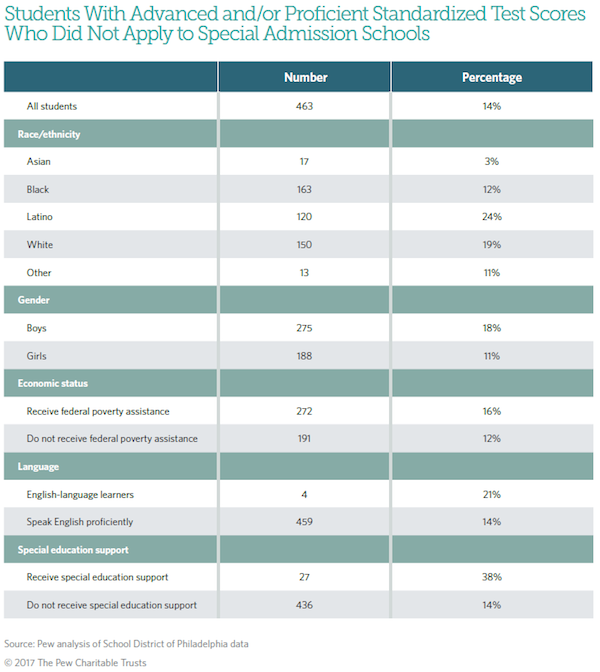

Nearly a quarter of the Latinos who had good enough test scores to get into a special admissions school never applied. That was the highest of any racial or ethnic group. By contrast, just three percent of qualifying Asian students failed to fill out an application.

When Pew asked officials and community leaders to explain why qualified Latino students aren’t applying at the same rate as other groups they received a few possible answers. Some believe Latino students might be more reluctant to travel far from their neighborhoods, an assertion Pew said is backed up by research on New York City’s high school choice system.

Others said Latinos might be reluctant to attend schools where they don’t see many familiar faces. “If you visit a school and you don’t see people who look like you, you may not see yourself attending the school,” said Karyn Lynch, the district’s head of student support services.

Daniela Romero with the district’s office of community engagement said school leaders needed better outreach to make sure Latino students and their families — especially those who don’t speak English — know how to navigate Philadelphia’s maze of choices.

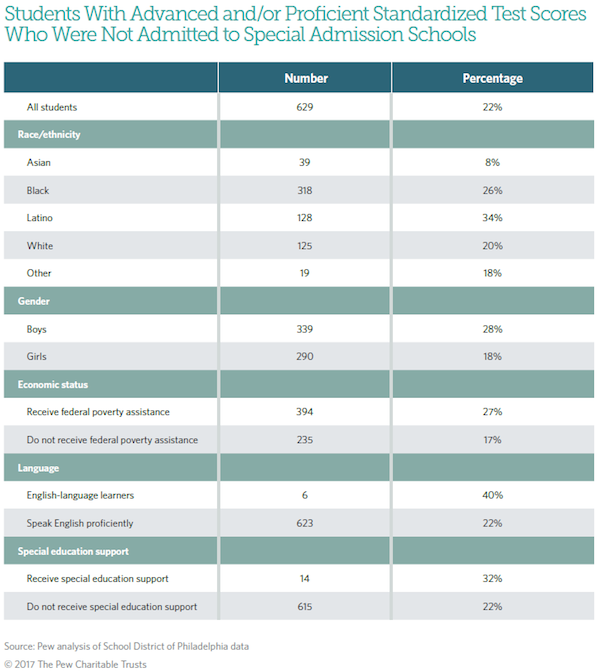

But even among Latinos who did apply for these coveted high school spots, the outcomes indicates a disparity. Almost 35 percent of Latinos who had qualifying test scores were rejected. That was, again, the largest percentage of any racial or ethnic group.

Pew also found that 11 percent of the students who wound up at special admissions schools didn’t actually have the test scores needed to get in. This wasn’t a nefarious abuse of the system, Pew said, but rather a reflection that some schools didn’t get enough applications from students who met the minimum test-score threshold.

And even among this cohort, Latino students lagged behind.

Of the non-qualifying Latinos who filled out an application, 15 percent were admitted. That was the lowest of any racial or ethnic group. Meanwhile, 39 percent of non-qualifying Asian students got into a special admissions program.

“In particular, with Latino students we saw at every point in this process [they] had lower, participation, acceptance and enrollment rates,” said Michelle Schmitt, the report’s lead author and researcher.

So does this prove there’s a systemic bias against Latinos baked into the city’s high school admissions process? Pew’s report doesn’t dive into the waters.

And there are other potential explanations for why Latinos and other groups are less likely to earn acceptances.

To get into a special admissions high school, students generally need to score proficient or advanced on the state’s PSSA tests, have good grades, solid attendance, and a relatively clean discipline record. The exact criteria vary from school to school. Students apply to high schools through a centralized admissions process, but the ultimate decisions are made at a school level.

That means a principal may look at two students who don’t meet the test score minimum and simply pick the student with the higher of the unqualified test scores. Or the choice could be purely subjective, and reflect some bias against Latino students.

Pew’s study doesn’t attempt to isolate the cause. And given the wide discretion afforded individual schools in Philly’s high school admissions process it would be difficult to determine how exactly these decisions are made.

What’s clear is there are demographic discrepancies in who attends the city’s top high schools, and they aren’t limited to ethnicity.

Female students, for instance, are more likely to have test scores that qualify them for special admissions schools and, ultimately, to attend selective programs.

Fifty-nine percent of students at special admissions high schools are female and just 41 percent are male. The exact opposite is true at neighborhood high schools, where 59 percent of students are male and 41 percent are female. Those numbers are influenced by the fact that Philadelphia has one all-girls special admissions school, but Schmitt said there’s still a gender gap even when that one school is eliminated.

Pew also looked at where highly selective schools were located and whether that influenced who applied, and they did find a correlation. It appears the clustering of these schools in Center City and Northwest Philadelphia did suppress interest in other parts of the city.

“This appears to be not just a matter of where the students lived but where the schools were located,” the Pew report read. “Enrollment was lower in ZIP codes where the schools were relatively far away or not readily accessible by public transportation.”

Pew’s report is also notable because it provides some basic census data on who applies to which of Philadelphia’s many high school programs. (For a full accounting, check out page 32 of Pew’s report.)

No surprise, the city’s highest academic performing schools attracted significantly more applications. Pew’s data shows just how wide that disparity is, though.

In all, the city’s special admission schools and programs received 28,762 applications. The school district’s citywide admissions programs — which are open to all, but have lower academic criteria — received only 7,556 applications (or about a quarter of what special admissions programs received).

The plurality of students in district-run Philadelphia high schools ended up in traditional neighborhood schools. Relatively few students applied to go to these schools, even though students can select a neighborhood school other than the one they are zoned to attend. Across the entire city, neighborhood schools received just 856 applications, a stark indicator of just how undesirable these schools appear to be.

Of the students who wound up in neighborhood schools, many were simply there because it was their local school and they didn’t participate in the citywide application process. Just over forty percent of students who went to neighborhood high schools never applied to another school. Another 23 percent applied somewhere else, but weren’t admitted. The final 36 percent of students were accepted to a special admissions or citywide high school, but chose not to attend.

The Pew report compared Philadelphia’s high school choice system to the college application process. Students submit as many applications as they want and can receive multiple acceptances. Also like college, admissions decisions in Philly are made at the school level.

Other cities take different approaches. New York City, for instance, uses a formula where students rank their preferred programs and an algorithm matches them to one school. New Orleans uses a similar method.

Pew did not say whether it recommends the Philadelphia approach or those from other cities. But in the report, researchers quoted Superintendent William Hite saying, “We’ve created more options for children and they’re taking advantage of them.”

He continued, “But we have a lot more to do when it comes to improving the options in all neighborhoods.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.