Mining mental illness: Munch’s artwork screams from Princeton University Art Museum

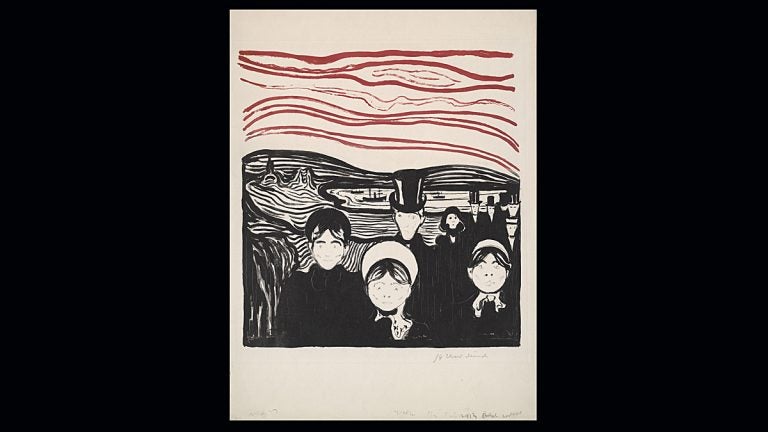

Edvard Munch, Anxiety, 1896. Lithograph

Edvard Munch is among the most recognized artists of all time. His haunting images continue to resonate generations after he made them, and often seem more relevant to today’s existential concerns. And yet the artist, who hoarded most of his prolific output until his death at 80, constantly battled depression, with a morbid fixation on thoughts of death and madness. He created some of the most romantic and sensual works of art yet was never able to form a satisfying love relationship.

Unlike Van Gogh – who influenced Munch — he benefitted from popularity in his lifetime. The popularity continues: his coveted work has been subject to repeated theft, and in 2012 one of four pastels on cardboard of his “Scream” – a painting recognized even by those who never took an art history class – broke a record when it sold for nearly $120 million.

A poster of Munch’s “Madonna,” depicting a femme fatale in sensual rapture, framed by snaking spermatozoa and a fetus – symbolizing, for Munch, the unwanted life that originates from sexual pleasure – is screaming across the Princeton University campus to announce Edvard Munch: Symbolism in Print, at Princeton University Art Museum through June 8. Twenty-six etchings, lithographs and woodcuts show Munch (1863-1944) as one of the greatest printmakers of the modern era, from his formative years to his triumphant exhibitions of the Frieze of Life, which included variations of his best known paintings on the themes of love, anxiety, sexuality and death.

“Printmaking allowed the artist to reach a broader audience than his paintings alone could,” says Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings Calvin Brown. “In addition it provided Munch with a seemingly endless range of techniques through which to express universal themes.”

A lot of Munch’s angst can be traced to his childhood. Raised in Oslo – then Kristiana – Norway, Edvard’s father was a doctor and military officer. His mother died when he was 5 and his sister Sophie died a few years later, both from tuberculosis. Another sister was institutionalized for mental illness, and a brother died of pneumonia.

Edvard’s father tutored him in English and history, telling vivid ghost stories and tales from Edgar Allan Poe. The elder Munch was a fanatic fundamentalist Christian.

“From him I inherited the seeds of madness,” wrote the son, himself a sickly child. “The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born.” The oppressive religious milieu his father created led to macabre visions and nightmares.

Munch’s father viewed art as unholy. In 1881, Edvard enrolled at the Royal Academy of Art and Design and by 1883, was an established painter, having shown in Oslo, Copenhagen, Paris and Berlin. As he developed some of his most iconic pictorial themes, he was invited to exhibit at the prestigious Berlin Artist’s Association in 1892. Because of the work’s provocative subject matter, and a rawness confused with the unfinished, outraged members of the association closed it after a week.

At the same time, other artists were sparked by Munch’s bold work.

Munch’s father died of a stroke in 1889, leaving the family destitute. It unhinged Munch and he was gripped with remorse that he hadn’t been with his father when he died.

Munch supported himself by charging admission to exhibitions. In order to increase his income, he started with intaglio techniques: etching, aquatint and drypoint.

“His first major theme was love – its origin and development and ultimate demise. He had six paintings that correspond to the various states of love,” says Brown.

“The Kiss” depicts a nude couple embracing, arms entwined, in a darkened room before an open window. Their passion allows them to melt into a single mass, oblivious to the people walking the streets below. “The contrasts between light and dark, public and private, give this image the psychological tension of a clandestine passion that would have shocked traditional Victorian sensibilities,” says Brown. “Both Rodin and Klimt also worked with this trope.”

By 1895, Munch started revisiting his key themes with lithography, which enabled him to include more color. He printed “The Sick Child I” — his memorial to his dying sister Sophie — and “Madonna” and “Vampire II” in 1895, then a year later produced lithographs derived from his paintings “Anxiety” and “Death in the Sick Room.”

“Anxiety,” like “Scream,” depicts people with ghostly faces walking at the edge of the Kristiania fiord at sunset. Munch wrote of the psycho-biographical subject: “I was walking along the road with two friends. The sun set. I felt a tinge of melancholy. Suddenly the sky became a bloody red… I stood there, trembling with freight. And I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature.”

With all the tragedies befallen him, Munch felt powerless against the forces of nature. He believed his paintings relating his dreams of divine universal psychological states were tantamount to Freud’s “talking cures.”

It was after seeing Gauguin’s Noa Noa prints that Munch began to experiment with color woodcuts, expanding his vision of what printmaking could do. Munch’s woodcuts were often made from pine or other soft woods weathered to impart a grain or texture.

The theme of a forlorn man and a dominating woman fascinated him. Munch had two great failed romances, first with Millie Thaulow, the wife of a distant cousin with whom he met clandestinely for two years. He was tormented after the breakup. In “Jealousy II,” he depicts a jealous man as he meditates on a seductively draped female nude engaging the attentions of a fully dressed man beneath the branches of an apple tree.

In 1898, Munch began a relationship with Tulla Larsen. She wanted to marry but he was afraid to commit because he wanted to remain dedicated to his art. He was afraid of bringing newborn life into a bleak world. “Like Rodin, he was afraid marriage would rob artistic and newfound independence,” says Brown. Larsen left him and married another artist. Munch took it as a betrayal and dwelled on the humiliation.

“Ashes II” is another expression of jealousy or regret. A man cows down as he remembers a former relationship with a woman with flowing red hair emerging from the woods where they went to have their affair.

In 1908, hearing voices and having hallucinatory paralysis, Munch collapsed and checked into a sanitarium. He cut back on drinking, regained mental stability, and got back to his easel, but most art historians agree his greatest work was behind him. Edvard Munch: Symbolism in Print is bracketed between his 1892 rejection from the Berlin exhibit to his final success in Berlin in 1902.

Edvard Munch: Symbolism in Print is on view at the Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton University campus, through June 8, 2014.

_____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.