I wrote a letter to Philly’s mayor asking for an end to the gun violence that took my beloved cousin. 16 years later, I’m resending.

Sakeenah Benjamin was 10 years old when her cousin was killed right around the corner from her house. Sixteen years later, she is still dealing with the pain.

Sakeenah Benjamin holds a photo of her cousin Manny, who was shot and killed in her West Philly neighborhood when she was 10 years old. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Lamont was my big cousin. I called him Manny — he was 21 years older than me, and a friend I could rely on for a big smile or laugh.

He was murdered on Jan. 28, 2004, over an argument of mistaken identity. He was 31-years-old: the 26th person killed in a year that ended with 330 reported homicides.

I was 10-years-old when he died, living in West Philly, where I’ve lived all my life and still live.

The most painful night of my childhood began with a knock at the door at dinnertime. There was nothing unusual about it at first: Family friends often stopped by our house, located on a beautiful street with lots of kids.

The normalcy ended with a blast of cold air from the open door and a terse sentence: “Manny was shot at the deli, I don’t know if he’s going to make it.”

I saw Manny the day he was killed. He helped me with homework that afternoon and planned to stay for dinner. As my father cooked the meal, Manny told me he had to go but would come back to eat with us. I pleaded with him not to leave because dinner was almost ready. He headed out the door and walked to the place where he met his untimely death. Manny was being laid to rest the next time I saw him.

The “deli” or stop-and-go is at the corner of Dewey and Market streets, exactly a 45-second walk from my childhood home. Stop-and-Go storefronts in Philadelphia are open for business today, with store owners who stand behind bulletproof glass and act as the main vessel of alcohol and crime in the community. In 2017, WHYY contributor Solomon Jones wrote about the local stop-and-go issue and how it negatively impacts our community.

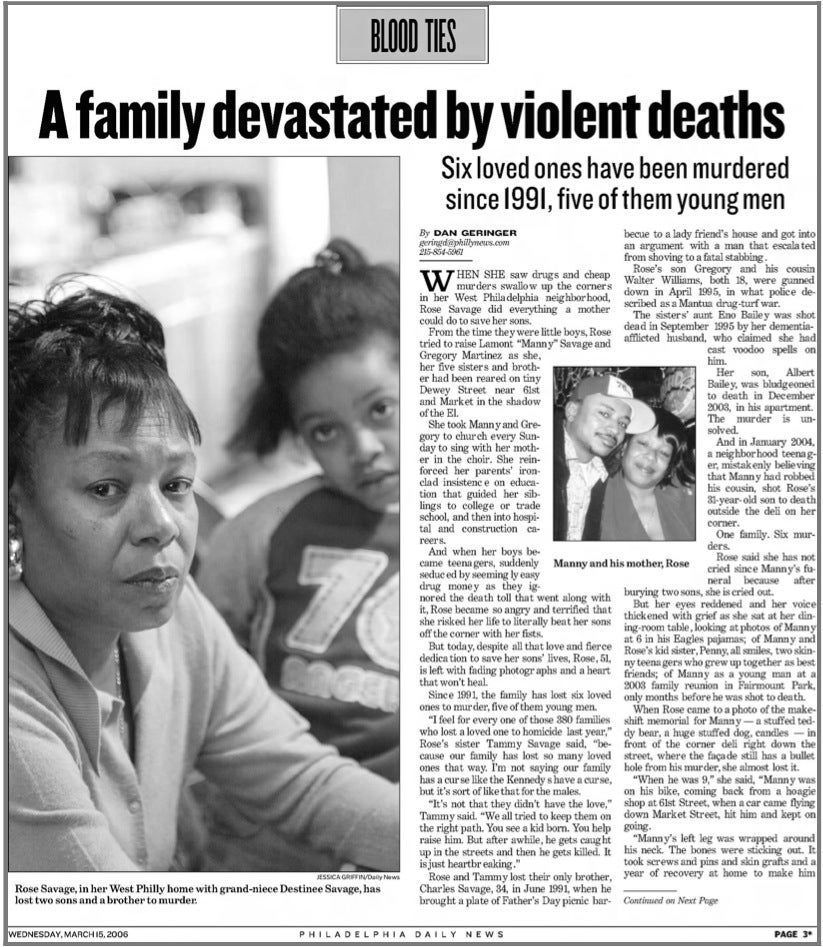

Manny wasn’t my first relative to die to violence. My family’s story is harrowing, the Daily News did a feature on the six murders of my uncle, great-aunt, and cousins, from 1991-2004. I didn’t know my uncle Chuck, who was fatally stabbed in an argument in 1991; my cousin Gregory (Manny’s brother) 18, killed during a drug-related war; my cousin Walter, killed leaving Gregory’s funeral; my great-aunt Eno, shot-and-killed in 1995. Eno’s son Albert was murdered in 2003. I never got to know any of the family members mentioned. We never laughed together, loved one another or got a chance to live in the accomplishments of each other. When a person dies to violence, they are snatched from love, warmth, and family. They aren’t given a chance to say goodbye or see you later—just taken, leaving grieving family members with memories frozen in time.

Manny’s killer didn’t think about the dinner he would miss with his family or the goodbyes he’d never get to say.

He didn’t think about me: a child who learned too early about the dangers beyond her block, lined with plants and brick houses painted with bright colors. I wanted to be a kid like those growing up in neighborhoods where the big worries were scratches from falling off a bike.

Shortly after Manny’s death, my mother’s friend Emmy was shot and killed walking home in Southwest Philadelphia. Manny and Emmy’s untimely deaths were a turning point in my life. Something in me felt that my 10-year-old voice needed to be heard. I was fed up, tired, and afraid. I wrote a letter to then-Philadelphia Mayor John Street. I wrote this letter pleading with a broken heart for the gun violence to end in Philadelphia. I thought about me—what my family’s lost, and what other families have lost. Months after sending the letter, police stopped by my house to tell me they had read the letter. At that moment, I felt heard and seen and a sense of safety I hadn’t felt in a long time.

Gun violence hinders the hopes and dreams of families when their loved ones are erased. Are people becoming numb to gun violence? Yes. But not the families affected. While the world continues to turn, they struggle to move forward from a nightmare, be strong and live in ways that are easier said than done.

I carried the pain of Manny’s death for a long time, and even as an adult, it haunts me. I’ve been afraid to be away from my family for too long at a time. I’ve gotten anxious and stressed and erratically thought about what could happen to them when we’re apart. I’ve learned how to cope, recognize my feelings and how to process them. Over time it’s gotten easier to tell the story of my big cousin Manny. I’m sure I’ll always have memories of the night he was tragically killed. When I’m having a hard day, I think about how he has inspired me and I know that he wouldn’t want to see me give up.

More than 50 people have been killed in Philadelphia already this year by homicide, most of them with guns. If I were to send a letter to Philadelphia’s current mayor, Jim Kenney, I would tell him this: We need to end gun violence. Gun violence advocates and community liaisons work tirelessly to end straw purchases and to keep guns off the street, but more needs to be done. I don’t have the answers, I’m willing to work alongside my community to figure them out. I know Philadelphia should be a safer place to raise children and live. This is our problem, and we must fix it now.

Sakeenah Benjamin is the public information coordinator at WHYY. You can reach her at sbenjamin@whyy.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.