How genetic is addiction? Camden researchers are collecting brains to find out

To better understand opioid-use disorder, Camden researchers are starting a biobank to study brain and blood samples of people who’ve died of overdoses.

(DedMityay/BigStock)

What if doctors had an algorithm to predict how likely a patient was to become addicted to opioids?

Researchers at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research in Camden are teaming up with clinicians at Cooper University Hospital and Rowan University to try to do just that. They’re one year into a study that aims to better understand the genetic factors that lead to opioid-use disorder and overdose.

The three-year study, which has received $4 million so far from the state of New Jersey, has three components: a biobank of brain and blood samples from people who died of opioid overdoses, as well as two clinical studies — one of those in treatment for opioid-use disorder, and one of people who have been prescribed opioids for chronic pain, but who do not have opioid-use disorder.

For the biobank of brain and blood samples collected from those who died of opioid overdoses, the research team is working in partnership with the medical examiner for Camden, Salem, and Gloucester counties and has been recruiting among next of kin there for the past several months. So far, the researchers have 10 blood samples. The group collected its first brain last week.

There were more than 3,000 overdose deaths last year in New Jersey, with those three South Jersey counties accounting for more than 15% of the deaths.

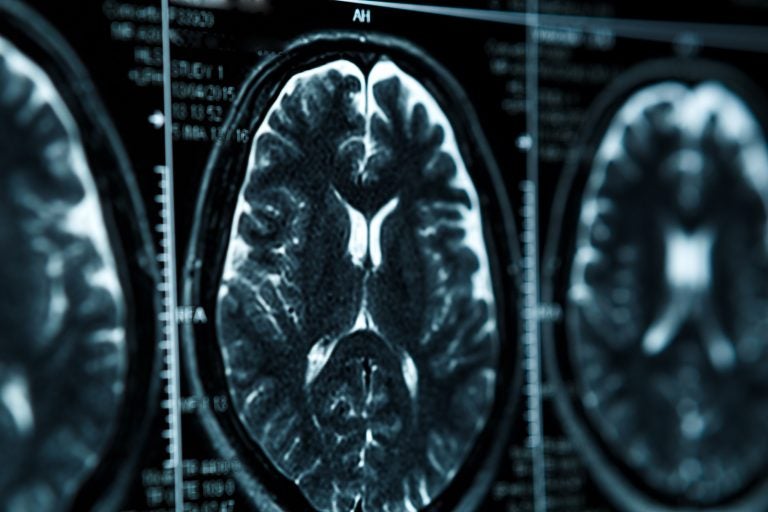

By taking biopsies of the brain samples, the researchers said, they can examine regions of the brain known to be associated with behavior related to addiction, such as reward pathways, genetic variation associated with dopamine and enzymes that process and respond to dopamine, and decision-making. From there, they can create a resource of samples that can be distributed to others around the country doing research related to opioid-use disorder or addiction.

“This is the first biobank of its kind in the nation,” said Alissa Resch, chief scientific officer at Coriell.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, roughly half a person’s risk for becoming addicted to drugs is hereditary.

Resch added that while her team would be looking to build on the existing research that finds certain genetic traits associated with addiction, she hopes the biobank will offer an opportunity to observe new patterns, too.

“You can also use the genetic information from DNA to basically identify new genes that would potentially be involved in these disease pathways,” she said.

The researchers plan to use toxicology reports from blood samples to precisely determine the combination of drugs that were in a person’s system when he or she died. They hope that information can be useful to public-health officials in identifying particularly potent drugs on the market, and in longer-term research.

For the clinical component of the study, the researchers are collecting blood samples from participants in Cooper Hospital’s medication-assisted treatment program for addiction and from chronic-pain patients who are taking prescription opioids, but are not addicted. The idea is to help develop a risk-assessment tool for doctors to use when prescribing pain medication for chronic pain or transient pain after surgery.

“If they knew the person was high-risk, they might give them a different drug or a lower drug or monitor them more closely,” said Stefan Zajic, the clinical lead for the project. “Same thing goes for patients who’ve already developed opioid-use problems — if a doctor knows that those patients are at a higher risk of overdose or relapse, they might adjust their care correspondingly.”

Zajic said that while he is aware that research shows most people who take prescription opioids do not develop addiction, he hoped cutting down on the overall number of prescription opioids would help mitigate overall access to the drugs, even for those not prescribed.

Though conclusions from the study probably will not be completed for a few years, top national officials agree that research on vulnerable populations who use drugs is sorely needed.

“People who start injecting drugs don’t typically volunteer to talk to us and say, ‘I’d like to be a part of your study,’ so figuring out how to study a high-risk population has been difficult for researchers,” said Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In a sense, Zajic said, each of the research groups in this study will serve as a control group for the next.

“In our pain study, we have many people who are on opioids and are not having problems with them — that’s a really good control group for people who are in our addiction study who do have problems with opioids,” he said. “Similarly, the people who are in our addiction study — they’re using opioids and they have not died yet — so they are a good control group for people in the biobank who have died from that addiction.”

In addition to genetic and epigenetic data, the researchers are also looking at environmental risk factors involved in a person’s likelihood for misusing opioids, developing opioid-use disorder, and overdosing, such as a history with substance use and trauma.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.