How designers are remaking spaces for our new socially distanced lives

Modular systems, flexible spaces and ‘human ingenuity’ on the rise as architects solve new social distancing puzzles.

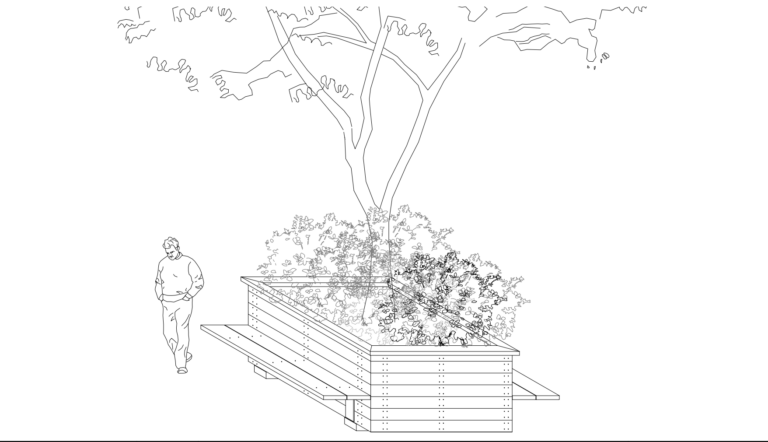

An artist's rendering of a site redesign by Community Design Collaborative’s Design SWAT team. (Courtesy of Community Design Collaborative)

COVID-19 has reclassified many workers as first responders. Doctors, nurses and medical professionals, transit workers, garbage collectors, and grocery clerks all come to mind. Architects do not.

“People don’t typically think of architects as first responders,” said Amal Mahrouki, director of legislative affairs with AIA Pennsylvania. “But they can be…if they’ve gone through the right training.”

Slowing the spread of the novel coronavirus requires immediate adjustments to how we use and inhabit buildings and space.

From redesigning schools and offices to allow for socially distanced use to repurposing buildings for medical use and retrofitting existing hospitals to serve the urgent demands of a pandemic, architects and designers are finding themselves facing a new kind of demand.

The Italian architecture firm Carlo Ratti Associati made headlines in April when their designers used shipping containers to create intensive care units (ICUs) for COVID-19 patients. A temporary hospital in Turin adopted the prototype.

Closer to home, city officials spent $5 million turning Temple University’s Liacouras Center into a fully operational hospital, retrofitting the North Broad Street arena with modular isolation units and beds lined up in efficient, carefully distanced rows.

“We’re really dealing with ‘what does public health need right now to do what they have facing them today and tomorrow,’” said Al Comly, disaster assistance coordinator and a long-time member of the AIA National Disaster Committee.

As concerns grew last month about hospital overflows and potential bed shortages, the AIA’s Pa. chapter put out a call to connect its members to health care organizations in need of designers to help retrofit medical buildings.

The need for surge facilities never materialized locally and so there wasn’t much response to that call. But AIA’s members stand at the ready — however they can help.

“Whatever they need, they can make the ask to us and we can be the conduit and connect them with members across the state,” Mahrouki said.

Designing for distance

For Philadelphia’s Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission, architects proved helpful as staff struggled with how to provide services in an old building with only one main entrance.

The Mission provides housing and meals to people experiencing homelessness out of a historic building on 13th Street north of Vine. With other facilities shut down or reduced by the pandemic, the nonprofit knew it had to adjust to meet increased needs while adhering to social distancing guidelines.

The Mission began offering grab-and-go food service, in lieu of the seated meals they typically host.

But the line for food quickly became too crowded to be safe. The building’s cramped entry created hazardous bottlenecks.

Meanwhile, the large dining hall was going empty without meal services happening.

If the Mission wanted to keep feeding people, it needed help reconfiguring its spaces. Enter: The Community Design Collaborative’s Design SWAT team. The Philadelphia design collaborative offers pro-bono design services to community organizations and the 13th Street Mission became the pilot project for its emergency response unit.

The Design SWAT Team got to work quickly. What would typically be a six-month process happened in one week.

The team familiarized itself with the facility and its challenges through a virtual site tour. Designers got feedback from the Mission’s staff about their ideas for adapting the space during two virtual design reviews.

The pro-bono architects then drafted a new socially distant queuing system for grab and go meals. They made plans to install permanent handwashing stations and convert the dining hall into a more comfortable and functional multi-purpose room. The designs are now being implemented.

The Collaborative’s interim executive director, Jenn Richards, said she hopes other frontline organizations facing challenges with their space think to seek out help from the architectural sector. She described benefits to working with professionals used to solving problems related to physical distance and proximity.

“People will be making these decisions anyway,” Richards said. “Wouldn’t it be great if you had someone who understands how space works and how people relate to space?”

Modular systems, flexible spaces and ‘human ingenuity’ on the rise

But many of the pandemic’s most enduring influences over the built environment won’t be felt during the pandemic itself. They will evolve over the next several months and years.

“I know architects love to be part of the emergency response team, but let’s face it, architecture and design is really slow,” said David Moos, principal of Coscia Moos Architecture, a Philadelphia-based firm that takes on, mostly outpatient, health care projects.

Moos believes that an appreciation for flexible and adaptable space in health care facilities, and public spaces, in general, will be one of the biggest takeaways to emerge.

“I do think there’s going to be a big change in the way health care is looked at in future,” Moos said.

Incorporating modular systems will also be key, he said.

Michael Marmion, an architect at NORR who works on health science projects, predicts a surge in demand for spaces where patients can be treated in isolation.

“Isolated space may just be part of the program of new health care facilities moving forward,” Marmion said.

NORR has seen a number of early requests from clients coming in regarding planning and research for future retrofits, but, so far, work has been limited to research, he said.

“Everyone we’ve been in contact with, if they’re still in the hospital, they’re still dealing with the increased patient load and clinical side of this,” Marmion said.

NORR’s Toronto office has even embarked on some preliminary in-house design challenges, taking projects they’ve worked on and running tests to see how efficiently they can convert them to COVID-19-ready facilities. The research will inform future projects.

After all, it may be a while until organizations make permanent changes and conversions.

“Every institution is different,” said Christina Grimes, an associate principal at Ballinger, an architectural and engineering firm. “There are some that are very much in the pressure of the moment and are really just trying to figure out how to get to the next hour, let alone the next week.”

Grimes anticipates that most of the meaningful design-related discussions will happen on the other side of the pandemic. She feels that a careful evaluation across institutions might help identify those small, innocuous-but-critical design factors that made a difference. It might be as simple as adding extra electrical outlets in hallways, for example.

“Some of the human ingenuity that’s coming out of this is pretty striking,” Grimes said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)