Goodbye, cruel world: Cursive signs off

Having good-looking penmanship places you just above blacksmiths or switchboard operators in terms of usefulness. You are master of an extinct universe.

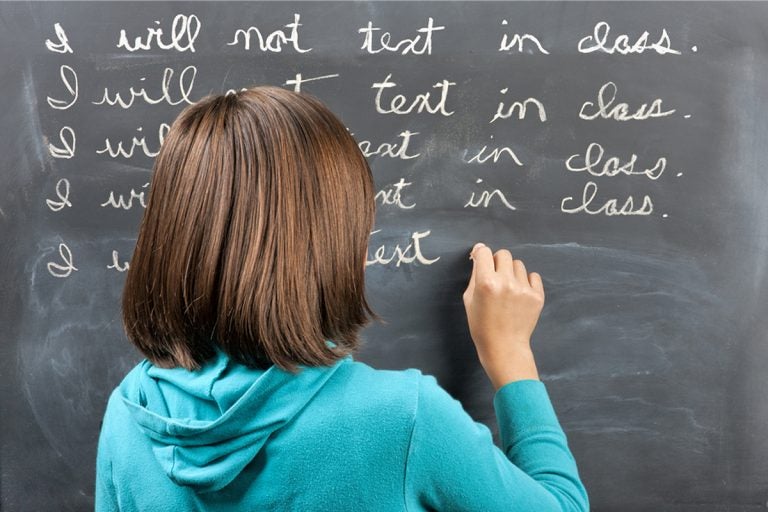

Old and news ways (gjohnstonphoto/Big Stock Photo)

Progress is not only measured in the new, but in what falls away. Once-essential items vanish into memory … or the basement. Before long, it’s as if they never existed. Today’s Bluetooth is tomorrow’s eight-track tape, whatever that was. Today’s iPhone is tomorrow’s older, cheaper iPhone.

So it is with life skills, and those who hang on to old ways of doing things are quickly scorned. This means you, if you read maps, use a dumb phone, wear a watch, and take notes with a pen on paper — and do it in writing.

On money, it still matters

In case you’ve been too busy dotting I’s to notice, cursive writing is rapidly becoming an unnecessary skill. Like churning butter. But not quite yet: Signing one’s name still matters for U.S. Treasury secretaries, whose signatures appear on paper currency (which is also on the list of endangered items).

Before he became Treasury secretary under President Barack Obama, Jacob “Jack” Lew had an autograph that looked like an old telephone cord — a series of loops. The president asked him to throw in at least one recognizable letter, joking that the stability of American currency was at stake.

The signature of current Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, a printed-cursive hybrid, is very clear. In fact, Mnuchin’s autograph is the complete opposite of that of his boss, which looks like a scary electrocardiogram.

Unless you plan to be secretary of the Treasury, though, handwriting really doesn’t matter much. Having good-looking penmanship places you just above blacksmiths or switchboard operators in terms of usefulness. You are master of an extinct universe.

Even if cursive writing is limited to one’s signature, it’s not essential. People hardly sign for anything anymore, in the sense that it authenticates who they are. All that’s needed is a scratch, a loose thread wandering across a tiny Etch A Sketch at the bank. We might as well go back to making an X. From robo-signing to shaky stylus squiggles, the signature, historically important and prized, has lost all meaning.

Handwriting: From distinguished to discarded

It would appall the nuns and other teachers who devoted significant hours trying to turn little children into John Hancock. It hasn’t been that long since all schools taught cursive, and Catholic schools turned it into an art, imprinting on their charges a clear, often beautiful, style so distinctive that a Catholic could often be identified by the handwriting.

Cursive was introduced to me in third grade, and was presented as a serious enterprise. Class began with warm-up exercises — row upon row of Slinky-like spirals and up-down hash marks. Next, we practiced actual letters. Sister would load chalk into a large comb-like device to create perfectly spaced lines on the blackboard, and then demonstrate how to form lowercase letters with perfectly rounded elements, and capitals with all the flourishes. In our seats, we copied from the board, erasing frequently, making holes in the paper. Eventually, we graduated to ink. A cursive alphabet was posted above the blackboard, for reference when penmanship was over.

Having good handwriting conveyed an inordinate amount of status in elementary school: It could make a star of an otherwise mediocre student. No longer. Handwriting is not taught in most schools, Catholic or otherwise. Cursive has been banished to the pedagogical dustbin, a pointless, time-consuming exercise for a world that barely needs to print.

A hard transition

This is hard to accept, for those raised with teachers checking to see if their lowercase A’s and O’s were well differentiated, or if the T’s were crooked. We still think our handwriting matters, but it doesn’t. Signatures don’t have to look good. They don’t have to be legible. They don’t even have to be ours.

That became clear when a helpful pharmacy clerk dragged her fingertip across the digital screen to save me from signing for a prescription. So to anyone still holding up checkout lines to carefully inscribe her name with a balky stylus, you can stand down. People behind you don’t understand, and they’re getting annoyed at the delay.

Instead, go home and transcribe any handwritten documents you want read in the future, because along with not writing in cursive, an increasing number of people can’t read it. And cheer up: This may open a whole new area of senior employment, like when the Rosetta Stone made it possible to translate hieroglyphics. Only instead of an ancient language, we’ll be reading history in our own handwriting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.