The Goals of Zoning Reform, Part III: Protecting Philadelphia’s natural and historic resources

In the next few weeks, both City Council and the Zoning Code Commission will reconvene. Council will begin holding public hearings on the commission’s proposals, and the ZCC will continue to fine-tune the draft code in preparation for submitting a final report. While it is ultimately up to Council to decide when to close public hearings and take action on the draft code, the ZCC and other stakeholder groups hope that the draft will be approved by the end of 2011.

In an effort to engage readers in the zoning reform process, PlanPhilly will post a series of stories over the next month that aims to measure how well the draft serves its stated purposes, which are laid out in the very front of the ZCC’s preliminary report. The reformed zoning code claims to promote four categories of purposes: sound planning principles, sustainable and environmentally responsible practices, growth and economic development, and fair and consistent procedures for the use of the code itself.

Each of these purposes carries a handful of sub-purposes, and in this series, PlanPhilly holds the draft code up to these purposes in order to evaluate its adherence to its goals. In the process, we hope to explain in general terms what zoning reform could mean to Philadelphians. If you haven’t been paying close attention to the four-year zoning reform process in our city, now is an excellent time to start.

For PlanPhilly

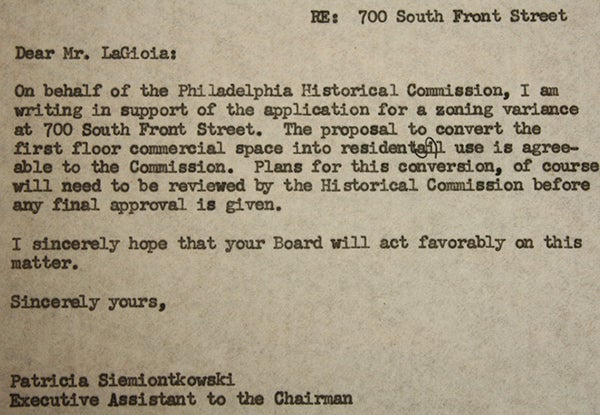

Atop the long list of Philadelphia’s natural and historical assets sit the obvious landmarks: Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, Fairmount Park and Pennypack Creek, the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, and the Italian Market. You can find all of those things on postcards. But we have more here than even the most hyperactive tourist—or lifelong resident—could hope to take in: a rich architectural heritage, a diverse (if sparse, in some areas) array of plant life, and hundreds of years of human history. In how many American towns could a mundane zoning meeting produce something like the following, from a 1972 Zoning Board of Adjustment hearing over proposed alterations to 700 South Front Street, a building once known as Widow Maloby’s Tavern:

In 1765, it was an owner-occupied dwelling with the first storey a Bar Room in the front parlor, a back parlor (for dining guests and family use) and a small kitchen wing adjoining at the rear … Thomas Maloby was a rigger by trade, the family tavern was supplemental income. Thomas died in 1765 and his widow ran the tavern for many years. Other tavern keepers owned the building until the eighteen nineties when the small kitchen wing was replaced by the present back building for increased income by absentee owners.

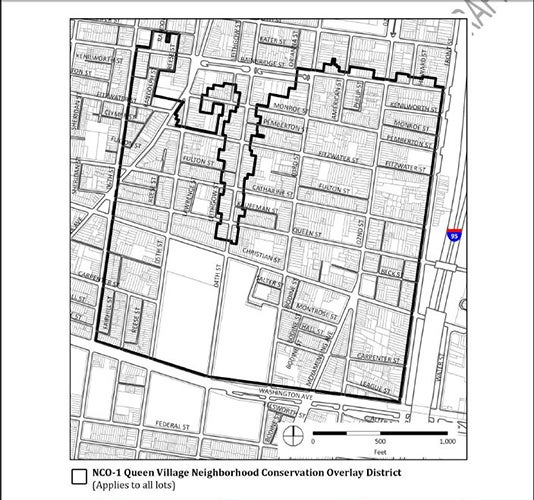

Today, that building is used as residential apartments, and is listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. It also sits within the boundaries of the Queen Village Neighborhood Conservation Overlay District, a special zoning overlay which is carried over into the draft new zoning code.

Mike Hauptman is the zoning committee chair with the Queen Village Neighborhood Association. His neighborhood is currently the only one designated as a Neighborhood Conservation Overlay District. Hauptman said that the designation, which Queen Village received a few years back, gave his group “the ability to locally create a zoning overlay that had locally designated guidelines.”

Before the housing market plummeted, Hauptman said, developers were buying up properties in Queen Village and turning them into homes with street-facing, first-floor garages. The QVNA didn’t like that, but Hauptman said that the process of getting designation as a historic district was too “expensive and cumbersome.” Many buildings in Queen Village were built in the 18th century, but Hauptman said that there was little rhyme or reason to which ones were designated historic. So, many un-designated buildings which were old enough to be considered historic were vulnerable.

“Nobody needed permission to demolish a building that wasn’t historically certified,” Hauptman said.

His group was able to put together a set of guidelines—such as a restriction on garages, regulations on materials to be used on the fronts of buildings, and amended height controls for the “littlest streets” in Queen Village—and get designated as an NCO district. The guidelines are administered by the City Planning Commission.

The Neighborhood Conservation Overlay District generally, which is explained in §14-504 of the draft, is but one component of the Zoning Code Commission’s stated goal of promoting sustainable and environmentally responsible practices by “restoring and conserving the City’s natural and historic resources.” Others include conservation overlays for the Delaware River and Wissahickon Watershed, a Special Purpose District for parks and open spaces, updated development standards for protecting natural resources, and a continuation of the City’s current historic preservation policy.

The City’s historic preservation policy is laid out in §14-1000 of the draft, and its purpose is eloquently stated at the outset: “It is hereby declared as a matter of public policy that the preservation and protection of buildings, structures, sites, objects and districts of historic, architectural, cultural, archaeological, educational and aesthetic merit are public necessities and are in the interests of the health, prosperity and welfare of the people of Philadelphia.” This language was adopted, and not created, by the ZCC, but it affirms in no uncertain terms the value of our city’s historic resources.

Specific regulations in the Historic Preservation chapter include requirements for the professional makeup of the Historical Commission, such as an architect, a historian, an architectural historian, and so on. The chapter also lists the criteria for the Commission to consider when deciding whether to designate a given property or group of properties for preservation. The code says that a property is eligible for preservation if it is associated with an important historical event, “reflects the environment in an era characterized by a distinctive architectural style,” is likely to yield important historical information, or “exemplifies the cultural, political, economic, social, or historical heritage of the community,” to name a few criteria.

Chapter 10 of the draft also requires that the Historical Commission compile a register of historic places in Philadelphia and make it available online “during normal business hours.” Recent visitors to the Historical Commission’s website will notice that this resource is not available. There is, in fact, currently no way to browse the historic register. If you have questions about a specific historically designated property, you can review documents related to it in Room 576 of City Hall.

But as previously mentioned, this part of the code has not been reformed by the ZCC.

“The ZCC took the position that they would make no changes to what’s generally known as the preservation ordinance,” said John Gallery, executive director of the Preservation Alliance. “I think basically we’re happy with that decision. We think the ordinance is good as it is.”

Gallery said that the Preservation Alliance was still planning on suggesting to City Council that one part of the historic preservation chapter of the code be changed. “In historic districts at the moment,” he said, “the [Historical] Commission often does not have control over new buildings being built in these districts.” The Historical Commission’s role is like a neighborhood association’s role in special exception zoning—that is, advisory. Gallery said his group wants to see the code changed to “give the Commission full authority to approve or disapprove new construction in historic districts.”

Gallery also pointed out that the chapter on historic preservation is only one part of the code that deals with preservation issues. He said that the Preservation Alliance would like to see some changes made to the Institutional Development District, such as making its minimum size 10 acres rather than 3, as the draft code now says. He said that there should also be “edge condition controls” to ensure sensible transitions between Institutional Development Districts and neighboring districts. Finally, Gallery said that his group was disappointed that the ZCC opted to eliminate altogether a component of the current code having to do with transfer of development rights.

The latter item provided a way for developers in certain areas to essentially buy floor area from historically certified buildings. For example, a developer working in a district where he is restricted to a maximum of five stories could obtain the right to build, say, two more stories from a three-story historical building in a district that allows up to five stories. Gallery said that this aspect of the code is poorly implemented and rarely used, but he was disappointed that the ZCC decided to drop it altogether rather than improve it.

For his part, Historical Commission executive director Jon Farnham supports the adoption of the draft in its current form. “I think that the current preservation section of the zoning code works well and I think that it will work just as well when moved to the new code,” Farnham wrote in an email.

Regarding Philadelphia’s natural resources, the draft code grants special protections to parks, open spaces, rivers, and streams. §14-407 describes SP-PO, the Parks and Open Space (Special Purpose) District. This district is intended to protect those spots in Philadelphia which “provide cultural and recreation opportunities; preserve natural an scenic areas; protect sensitive natural resource areas; and offer refuge from the built, urban environment.” Among the specific regulations in the SP-PO district is a requirement that any buildings comply with “the dimensional regulations of the most restrictive abutting district.”

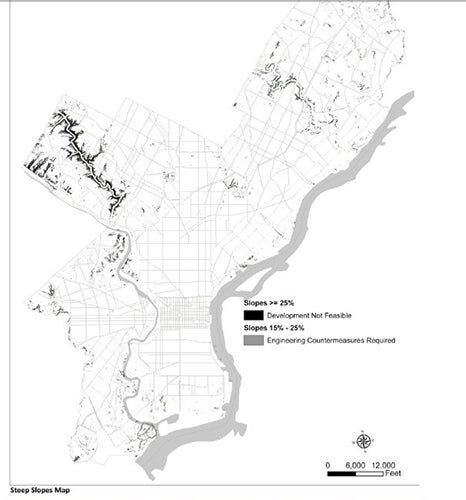

Development standards for open space and natural standards are laid out in §14-705 of the draft. These standards are intended to “promote safe and compatible development” and avoid “adverse impacts and degradation of the environment.” They forbid development on slopes of 25% or greater, protect stream buffers, and encourage the incorporation of existing vegetation into landscape plans. The code also contains specific standards for the preservation of “heritage trees,” which are defined as trees of any species listed on the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Heritage Tree Species List with diameter breast heights of at least 24 inches.

Cara Bertron, a research associate in the Historic Preservation program at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, said she’d like to see a better public education apparatus when it comes to preservation issues.

“Preservation is, at heart, not a fundamentally technical discipline,” Bertron said. But she admitted it gets harder to understand the further you get into specific legislation. The better access the public has to understanding the issues underlying historic preservation, the more effective the legislation will be in serving its stated purposes, such as §14-1001 (6): “Foster[ing] civic pride in the architectural, historical, cultural and educational accomplishments of Philadelphia.”

“It’s based on a really good premise,” Bertron said.

Next Up: PlanPhilly explores how the draft code upholds fair and consistent procedures.

Contact the reporter at jaredbrey@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.