Fishtowners feud at community meeting over St. Laurentius reuse proposal

On Tuesday night the Fishtown Neighbors Association held a zoning meeting and nonbinding vote on the future of St. Laurentius church. Developer Leo Voloshin stood before the massive crowd and defended his proposal to convert the vacant property into a 23-unit apartment complex, which many maintain is the only way to protect a property the Archdiocese of Philadelphia seems keen to tear down.

The event took place in the steamy and crowded basement of the Holy Name of Jesus church, where a mass of several hundred residents peppered Voloshin with questions about everything from the fate of the stained glass windows to the possibility of only renting to those without driver’s licenses.

The final count totaled 73 “community” votes for the development and 74 votes against it, while the “local” vote—from those within 500 feet of the project—came to 34 “Yes” and 94 “No.” The huge crowd represented the largest attendance of a community meeting about St. Laurentius yet, according to Venise Whitaker of the Faithful Laurentians.

The saga over the beloved institution has been unfolding for years. Designed in 1882 as the first Catholic church in Philadelphia for Polish immigrants, St. Laurentius was deconsecrated by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia in 2014 as part of the wave of parish closures begun in 2012. Plans for demolition were blocked by a spirited campaign that won historic designation from the Philadelphia Historical Commission. But since then church supporters have been split between those trying to save the building by converting it into housing—which they argue is the only way to raise the capital necessary to repair it—and a faction that sees such a use as invasive.

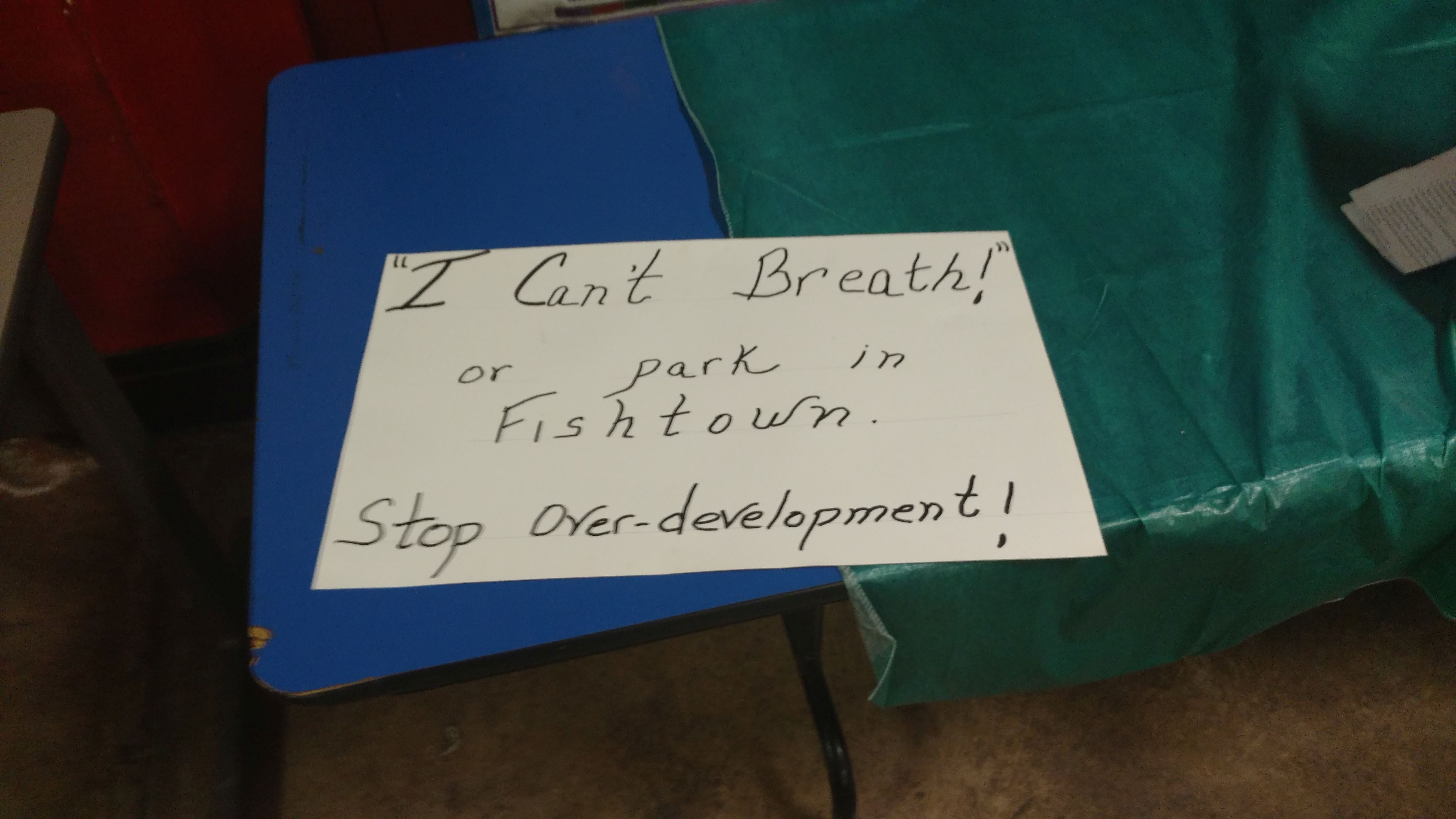

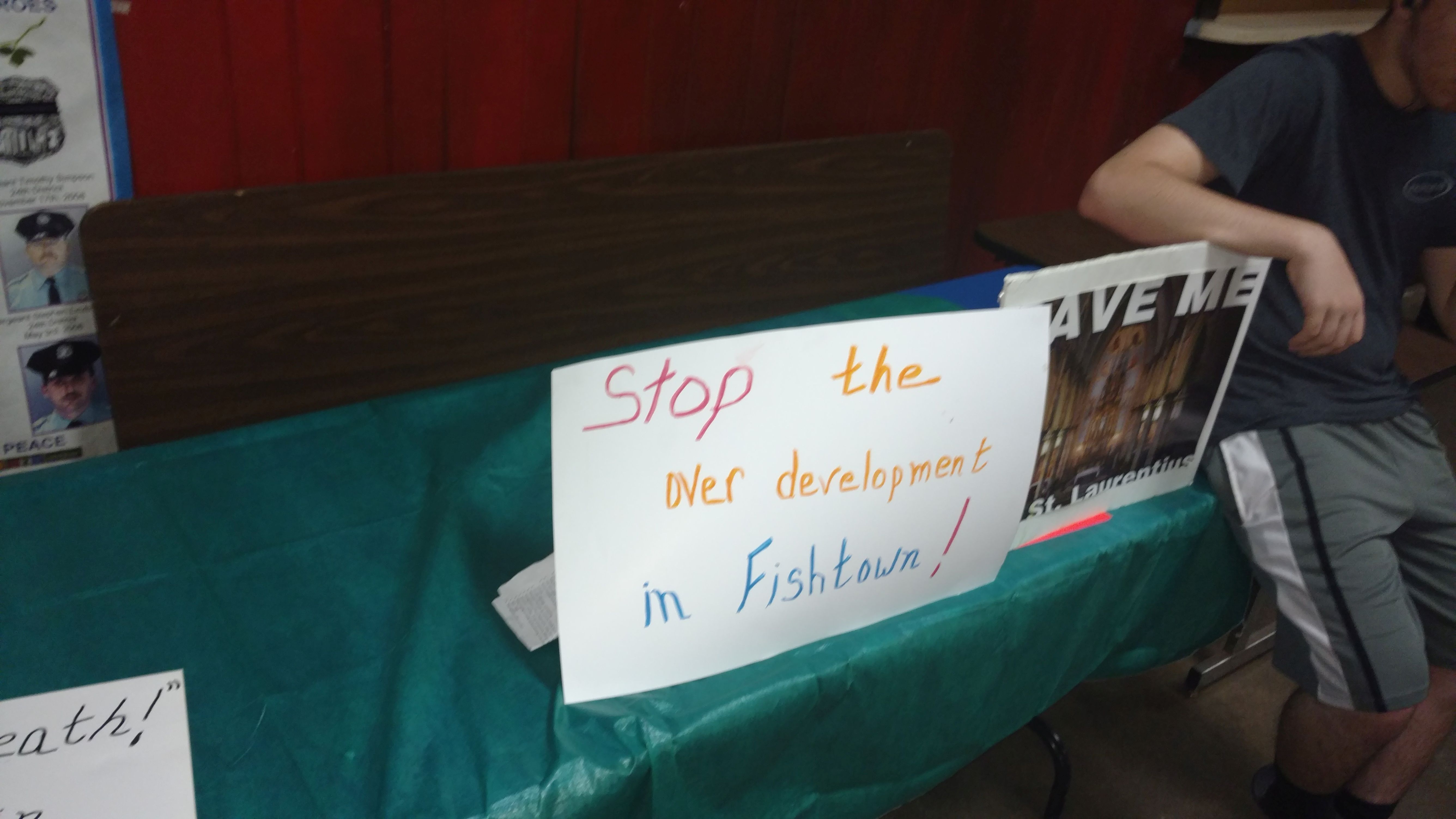

As the meeting unfolded, children romped around the back of the hall and one family spread out in the far corner of the room with coloring books and bags of snacks arrayed about them. But at various times the room seemed primed for an explosion, punctuated by heated rhetoric and at least one threat of fisticuffs. On a table in the back of the room a couple protest signs sat unattended, reading “Stop the over development in Fishtown!” and “‘I Can’t Breath’ [sic] or Park in Fishtown.”

The meeting began in a tense fashion, as the packed room heaved with emotion every time a question arose about parking. Under the revised zoning code of 2012, there are no parking minimums for projects that repurpose historically protected sites for reuse. Such a regulation could make a project like the proposed conversion of St. Laurentius prohibitively costly, but to many in attendance on Tuesday night it meant an already competitive quest for parking would become even more daunting.

“It’s already impossible to find parking because of those people,” said a goateed man in the crowd, who emphasized that many new residents of Fishtown owned both automobiles and bicycles. “They leave their cars parked and just ride their bikes. Then you have five different people with cars living in one apartment, a lot of them with Jersey tags.”

Voloshin emphasized that the units proposed for St. Laurentius were single-bedroom apartments in part to ensure that only one or two people would live in each unit. He said he’d been in communication with other developers in the area, like the Domani Developers, who only report less than ten cars in use among tenants of their 30 small apartment units in an old baseball factory on Tulip Street.

Later in the meeting preservation activist Oscar Beisert, who helped write the nomination to win St. Laurentius historic protections, asked if the parking question could be solved by targeting the units towards those without drivers’ licenses. Voloshin said that would violate the Fair Housing Act, but Beisert noted he’d heard of such tactics working in similar cases in other cities.

After the Fishtown Neighbors Association cut off questions about parking, most of the questions ranged over issues of signage (none are planned), placement of bike parking (in the basement), and the possibility that there will be dumpsters “billowing with trash” on the sidewalk (there won’t be).

The cleavage between those who want to preserve at least a semblance of the church’s old function, as well as the form, remained as strong as ever. Local design consultant Jesse Gardner received a storm of applause by suggesting that St. Laurentius could be saved for community use, and claimed to have a list of dozens of churches from around the country in worse condition that were saved.

“Leo I know you personally, but when I saw the number of units I knew the building would be completely privatized,” said Gardner. “All relationships with the space are severed. You will never be able to get in without knocking on the door and knowing somebody. Leo, have you considered working with us to have this continue as a sacred event space, not looking at the bottom line?”

Although many of the most vocal members of the audience seemed skeptical of the development, other voices interceded on the behalf of the proposed apartment. “The developer is not the enemy, the enemy is the archdiocese,” shouted resident Andy Chomentowski, before marching out the door.

Neighborhood activist A.J. Thomson, who is a fierce proponent of preserving the church building, became increasingly agitated over the course of the evening in defense of the project. He even verbally sparred with several other community members. By the end of the evening, his blue shirt completely soaked with sweat from the sweltering basement, Thomson still stood outside Holy Name arguing with other neighborhood residents.

“I’ve never met you sir, you called me a liar to my face,” Gardner stormed at Thomson, who replied that his opponent sounded like Donald Trump. “I’m a private citizen, you’ve never met me. That’s libel. Do you want to go outside?”

“I’m forty, how old are you,” Thomson lashed back.

Later he got into an exchange with Lois Skalamera, accusing her of drinking after she confronted him about the use of funds raised to save the building in the past. The conversation quickly devolved as Skalamera flung the accusation back at him, saying she wasn’t the one yelling and sweating profusely. After that Thomson spoke out less, although he still paced around the cavernous meeting hall and defended the apartment plan to community members one-on-one.

At the end of the night, before leaving to let the community vote, Voloshin answered some of the more conspiratorial questions with a testament of his loyalty to the St. Laurentius cause.

“I have no interest in taking on this project except to save the church, it’s the only reason I’m up here,” said Voloshin. “I’ve been grilled for about an hour now and you know what, I’m fine with that because this is a beautiful building and it’d be a damn shame to lose it.”

As the end of the night, groups of people discussed the apartment plan outside Holy Name Church, the church the Archdiocese merged St. Laurentius into upon its closure, and in small clusters of four or five on the street corners around the two churches.

Sitting on her porch of her row house, which is about half a block to the west of St. Laurentius, Skalamera wearily reflected on the meeting.

“I don’t care that it’s been deconsecrated, there’s a church on it so it’s sacred ground,” she said. “It’s not just a place of worship, it’s not just a building. It’s where we come together to celebrate, where we come together for Christmas. We need this place.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.