Finding work/life balance in the darkroom of the soul

The work/life balance is one of the first things that comes to most people’s minds when I ask them how they can be ‘human at work.’ While most of us feel this, I found that Philadelphia photographer Jacques-Jean Tiziou had a more visual way of making it real.

The work/life balance is one of the first things that comes to most people’s minds when I ask them how they can be ‘human at work.’ In short, most folks say that, first and most necessarily, they need space to just be human.

And when so many of us juggle work (sometimes more than one job), a partner, children or aging parents, and the overwhelming logistics of life, that space to experience simply being human is a rare commodity.

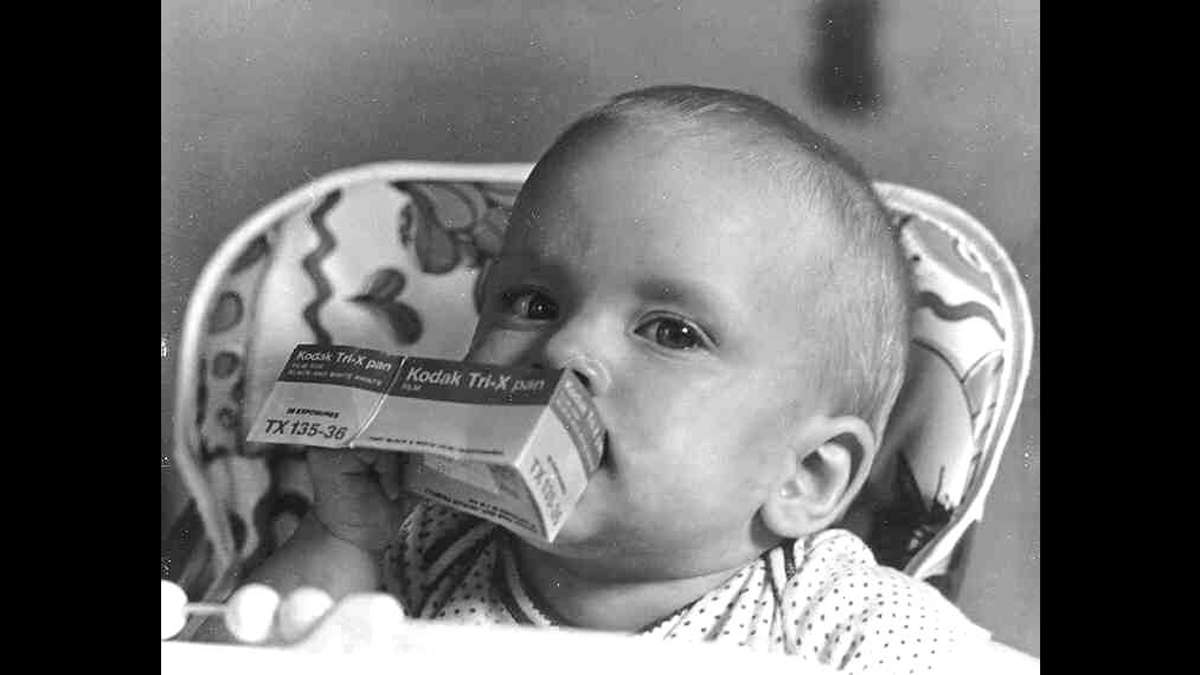

While most of us feel this, I found that Philadelphia photographer Jacques-Jean Tiziou had a more visual way of making it real. His ability to turn that feeling of needing space into pictures — literally — helped me to experience the question and the possible answers in a much deeper way.

In his earlier years, Tiziou says, he used to find that work-life balance more easily. But somewhere around 2007, he realized it had gotten pretty badly out of whack.

“I needed to create balance in my [photography] practice, in being more reflective about saying yes or saying no, professionally and personally,” Tiziou says. So he thought back through what had happened in his work in recent years.

He realized that he used to balance the overstimulation of being a photographer with the built-in solitary time he spent in the darkroom. “Even while I was working [in the darkroom], I was alone and quiet, and was processing and reflecting in a more inward way.”

Along comes digital

What changed for him was the onset of digital photography. “And with digital,” Tiziou says, “that new technology catered to the extroverted interpersonal work which I constantly did with people. It facilitated manic production but took away the solitary processing time. Without realizing it, I let it kick over and lost that element of balance.”

He looked at the number of digital photos he had (over one million, with 180k from the first year of digital alone), and the number of contacts in his phone (around 6,000), and he realized that he was way over-extended.

“I had started a lot of relationships that I wasn’t able to maintain or respect,” he says. “I realized I was spread too thin.”

So he began retreating. “It’s taken several years to unravel and process,” he says, “and the evolution continues.”

While that balance between work and inner life is always a living question, now he feels better able to judge when to say yes or no, and how to approach a new project or relationship.

Creating a safe space for himself

That was intriguing enough, but Tiziou makes a beautiful analogy between what he does in his inner “darkroom” and what he does in his work that makes him so effective as a photographer.

“One of the hardest and most important things I do is create a safe space for people,” he explains. He takes the act of photographing a person — “that can feel threatening and has societal baggage,” he says — and I tries to make it a safe space for his subjects.

As someone who’s been photographed by Tiziou, I know he achieves that goal really well. How?

“It involves splitting my mind in half,” he says. “One eye is open and seeing through the camera; the other is generally closed or scanning the periphery. One half of the mind tries to see you as your most beloved friends see you. My other eye is tied to the camera and thinking about technical details, background details, aperture, framing elements — to take care of the variables that make a good image.

“It’s an intense process, internalizing all of the stresses while keeping an outwardly comfortable appearance. It requires decompression time afterwards. When I started photographing non-stop without that darkroom time, I realize I was doing it in a way that made everyone else comfortable — but not me.”

Tiziou says that became a metaphor for what he wasn’t doing for himself: He wasn’t maintaining that safe space in his personal life that his darkroom had once provided.

Even the technical terminology hits right at the heart of the matter. “In the darkroom, the old orange amber light was called the ‘safe light.’ You turn negatives into positives. Metaphors. Processing film and prints was like soul- and heart-processing.”

Now, Tiziou can let the art and practice of photography, which defined him as a person, flourish without confining him as a person. He’s being intentional about re-creating that darkroom space through yoga and meditation — and by actually heading back to the literal darkroom this spring.

Tiziou’s story about his own evolution helped me to feel pieces of it in my own life, thanks to the images he used to describe it. It was just the beginning of a longer conversation.

“To continue to be a photographer,” he says, “is a bigger thing than just making pictures.”

But what about you? Do you feel the need to reclaim a “darkroom” for your soul? How do you know? Or if you haven’t lost it, how do you find space for it in and around your work?

Comment below or email me.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.