Finding the form with Cecil Baker

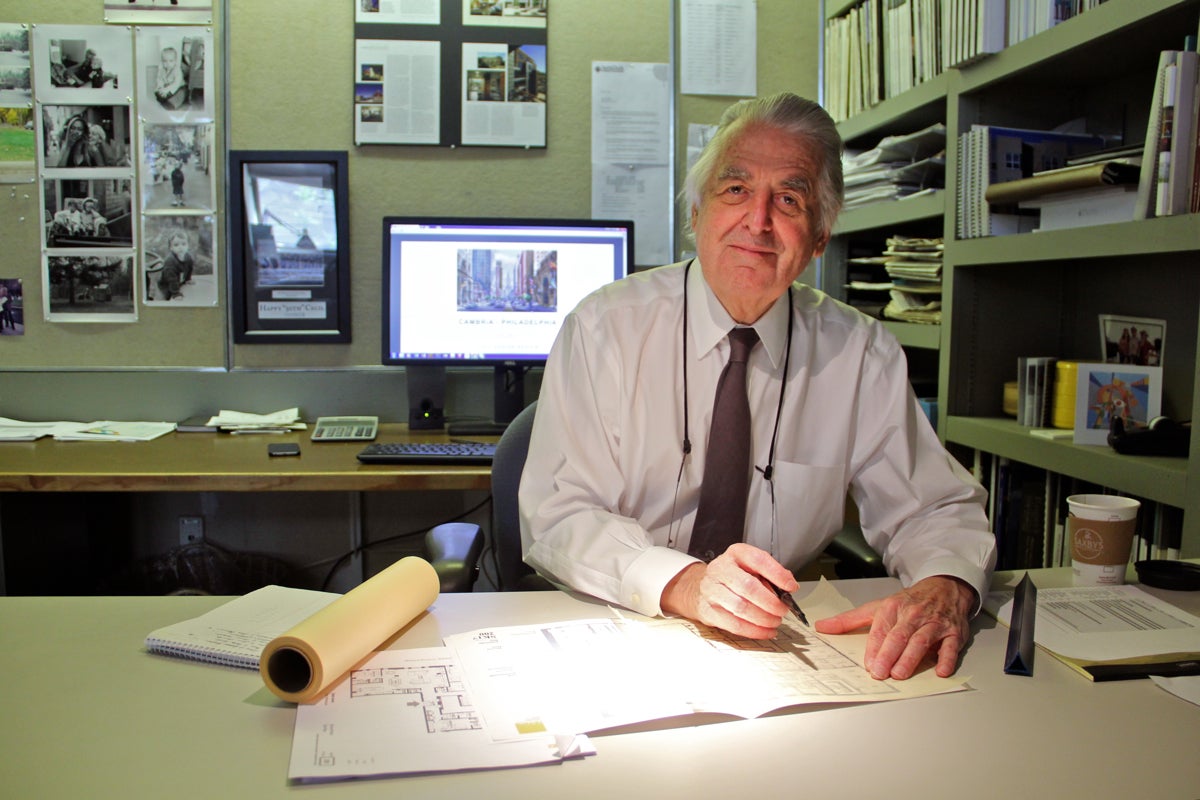

Cecil Baker will often pause before he speaks.

In meetings of the Civic Design Review Committee, he will sometimes lean back in his chair, further back than you’d expect, as though to establish interface with whatever deity he’s about to summon. Or he will hold his fingers an inch from his forehead, and shut his eyes, and appear to be digging very deep for the right thing to say. The pause may last for so long that when the utterance finally arrives, it will seem to have a special significance.

“Sophisticated poetry,” he might say.

Or, “It has got to be a great goddamn building.”

Or, “It’s a sad thing.”

These tics lend the silver-haired architect an oracular air. If you only heard him speak, you might assume that his own building designs tended toward the fantastical. But in fact, Baker’s designs—including Carl Dranoff’s under-construction One Riverside project on the banks of the Schuylkill, Tom Scannapieco’s soon-to-rise glass tower at 5th and Walnut, the Western Union condo building at 11th and Locust, and a host of small residential projects in Queen Village, Washington Square West and Old City—are characterized primarily by their sensitivity to context.

As Philly rides out the latest development boom, Baker has been getting more and more visible commissions, and has been willing to use the legally-powerless Civic Design Review seat as a bully pulpit. Could his approach catch on?

Baker describes his design philosophy as “the persuasion of place.” He prefers to use a sculptural metaphor: One type of sculptor has a vision, finds a piece of marble, and chisels until the vision is realized, while another type of sculptor finds the marble first and chips away at the cracks to find a new form within it. Baker puts himself in the latter camp.

Baker was born in Argentina, raised by British parents, and started a small development company in Philadelphia in the 1970s. Like other developers in Philadelphia, he came to understand the value of a robust conversation.

“You look to a site for its scale, you look to a site for where it fits in the ecological picture, you look to the site for where it fits to community goals and so on and so forth, but there’s that extra layer which is the people layer, which is the conversational layer of design.”

“That was an education for me in that I’d always been a believer that an architect should look to the site for clues before starting the whole vision thing,” Baker said. “What I came to realize in that process of being a developer was that very much part of the making of a piece of architecture or planning on a site was also our democracy.”

In his architectural practice, that sometimes means respecting neighbors’ design concerns. At One Riverside, which caused an early outcry despite being designed around the zoning constraints, Baker angled the tower to create the most minimal obstruction possible to surrounding views of the river. Because of concerns that a glass facade might reflect enough sunlight to fry an adjacent community garden, he made the building more opaque. In exchange for an extra story in the tower, he and Dranoff buried the parking garage below ground. The revisions turned the once-contentious situation into a rare kumbaya.

Sometimes it means designing with constraints from the very start. At 5th and Walnut, a luxury glass condo tower catering to a clientele that “wants New York,” Baker pulled the edge of the building back from the property line at two angles, so that someone standing at the Liberty Bell and looking at Independence Hall wouldn’t be able to see it.

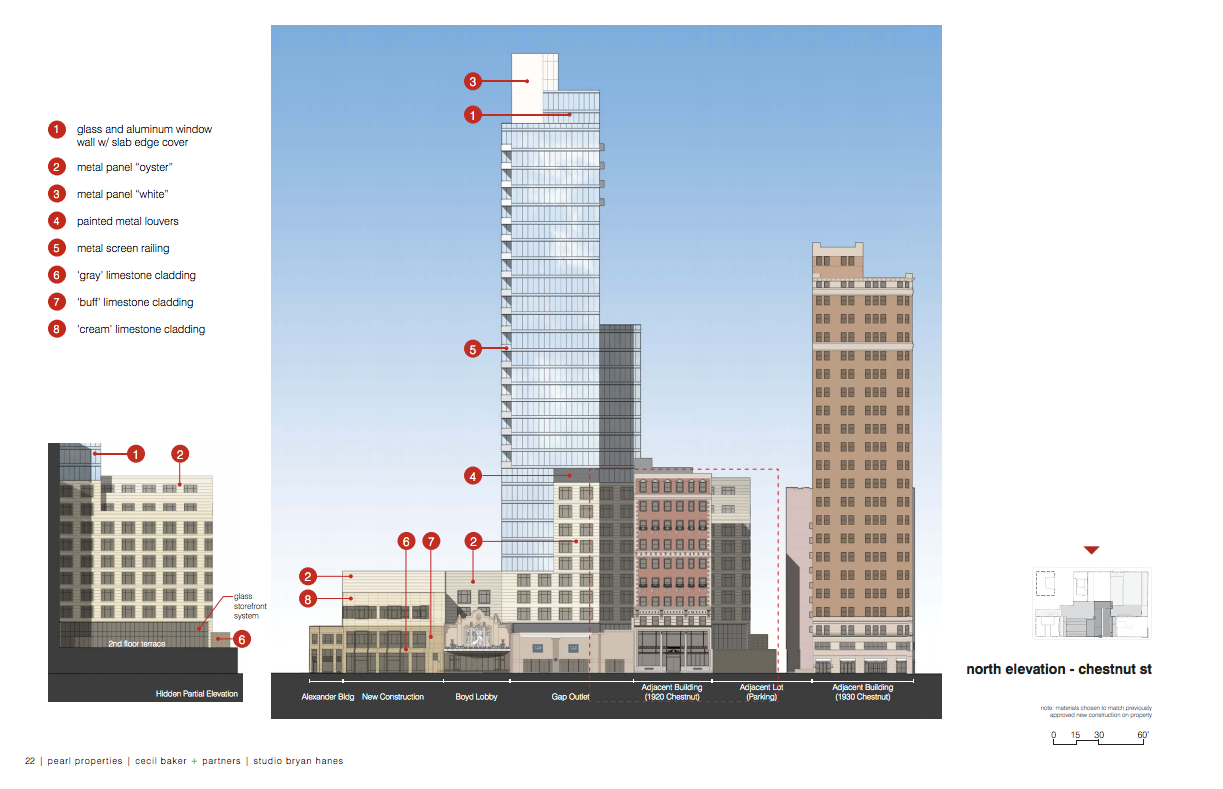

Lately, Baker, who spent some years on the zoning committee for Washington Square West Civic Association, has played the role of architect-to-the-rescue. A faction of the Center City Residents Association (CCRA) cried foul when Pearl Properties unveiled its proposal for a 27-story tower on the site of the former Boyd Theater. But rather than hiring lawyers to gum up the works, the neighbors hired Baker to look at the site and propose an alternative design.

“He got [Pearl] to understand that their proposal was utterly inconsistent with neighborhood architecture and what it feels like to be in Rittenhouse Square,” said Rick Gross, a CCRA board member who initiated the deal with Baker.

Baker flipped the orientation of the tower to reduce shadows on surrounding buildings, moved the loading docks, and suddenly, everybody liked the design better. Pearl eventually hired him as the lead architect for the project, which, he later confessed to Hidden City, made him a bit uncomfortable.

“He ultimately got a design that gave [Pearl] a fair amount of what they wanted by right, by volume, that fit incredibly well,” Gross said. “… He carries a certain level-headed quietness to what he’s doing that people respond to.”

In West Philly, Baker led the community-driven design of an apartment building adjacent to Clark Park. The building at 4224 Baltimore Avenue was conceptualized through a series of community meetings, and though the final product didn’t align with the zoning for the site, it earned the support of almost all of its neighbors.

“[Young people] don’t come from a place of fear, where my generation did,” Baker said. “By my generation, I’m largely talking about the hippies. That was my generation. We wrought a lot of change, and we did a lot of good things. But after it was all over, and we got our changes, we were the NIMBYs. … And the millennials have totally changed that paradigm in the city. It was evident at 43rd and Baltimore, places like that that you couldn’t have gotten those kinds of disturbances and not-living-with-the-zoning-code type things to happen if you didn’t have these young voices that were saying, ‘Hey, what about it? We don’t need to be this way. Let’s come out into the sunlight.’”

Alex Feldman, of U3 Ventures, a partner on the project at 43rd and Baltimore, said that Baker was the ideal architect to lead that kind of process.

“I think having an architect that first of all is talented but, second of all, someone that can convey what they’re hearing from a community standpoint into something that will ultimately be acceptable to them—that’s not second rate or watered down—is a huge talent of his,” Feldman said. “That ability to translate between community desire and well-designed and well-scaled buildings is fantastic.”

Baker has been declaiming from the conference table at Civic Design Review hearings for a few years now. Have some gravitas, he tells developers. Be joyful. Be serious. Be generous. Go back to the community and start again. Is the message getting across?

“I think one of the difficult things about CDR or any design review process is trying to find the balance between being concrete enough that people know what you want from them and aspirational enough that they know why you want it,” said Nancy Rogo-Trainer, who chairs the committee. “And I think that [Baker] provides that aspirational, poetic language. And my sense is that people understand what he means when he says it.”

Alan Greenberger, the former deputy mayor for economic development, thinks that the value of Civic Design Review, an innovation of the reformed zoning code, doesn’t show itself a project at a time. The long-term impact of the process will be that “the design ethos of the city will improve.”

“Developers are pack animals, by and large,” Greenberger said. “A few developers, by virtue of a particular project or a particular frame of mind, are able to do things that are different than everybody else, and they lead the pack. But most developers are looking for where the herd is going and follow it, because development is risky, and it’s less risky to follow the herd than to hang it out there by yourself.”

While Bart Blatstein has been weathering an onslaught of rotten tomatoes for his proposal at Broad and Washington in South Philly—a 32-story tower on a solid super-block, with a European-inspired retail village on the fourth floor—Baker has taken a gentler approach. At a Civic Design Review meeting last month, he said maybe the city should let Blatstein do the raised retail village. But could the entryway be better?

The rooftop retail village, Baker admitted to me, might puzzle the whole city but at least it’s an idea.

“Are there ways that we can inspire our developers to see our side as citizens?” he said. “Bart is, to me, one of the great examples of someone who’s just full of energy and ideas. Inga talks about the Good Bart and the Bad Bart and all the rest. Where does it come out? Well, it’s up to us to create the good Bart.”

Earlier this week, Baker showed me around his office, pointing out various projects he’d developed and high-end interior renovations he’d completed. He tends to work on the extreme ends of the market, for the wealthiest clients or for social-service agencies. His firm is currently working on a design for senior housing next to St. Rita of Cascia on South Broad Street and a private condo project on the waterfront. I asked him whether he prefers designing from scratch or remaking an existing building. He likes both, he said.

“When you have your hands tied, it tends to bring out the best in you,” he added.

His team was trying to figure how much of different types of housing would fit on a pier for the condo project on the waterfront. They might fit a few dozen low-rise houses, or a smaller series of taller, multi-unit buildings. Where were the best views? They could go for density bonuses under the terms of the Central Delaware zoning overlay, but adding retail space, for one, would be a tough sell with the developer. They calculated units. They sketched building outlines. There were, finally, two alternative schemes they could discuss with the developer.

Neighborhoods hope for good, sensitive architects. Developers like popular ones. Designers find creativity through constraint. Decades into a prolific career, Baker has found his form by blending all three.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.