Are female-led companies the answer to sexual misconduct?

Promoting more women to boards and the C-Suite is considered a critical step, but critics caution it is not enough, particularly when it comes to turning around a company.

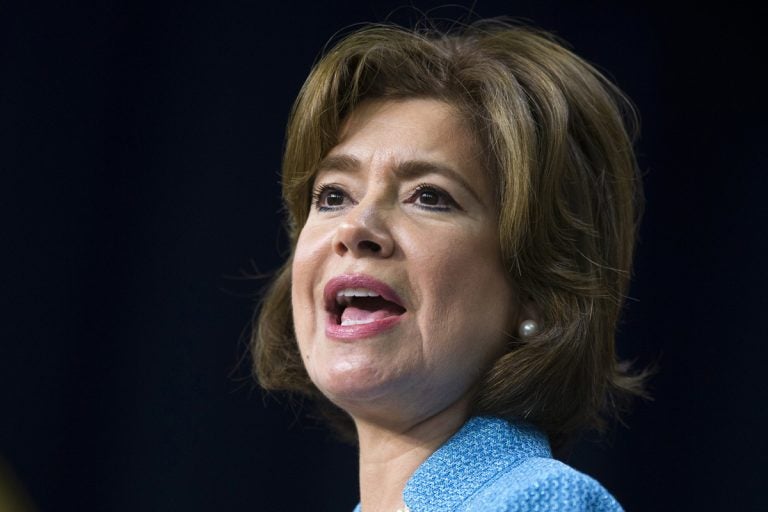

In this April 7, 2014 file photo, Maria Contreras-Sweet speaks during a ceremonial swearing in as Administrator of the Small Business Administration, in the South Court Auditorium on the White House complex in Washington. A group of investors led by a Contreras-Sweet offered to acquire Weinstein Co., rebrand it and install a female-led board of directors. (Evan Vucci/AP Photo, File)

The Weinstein Co. thought it had found a path to survival. A group of investors led by a respected businesswoman offered to acquire the company, rebrand it and install a female-led board of directors. It was an eye-catching idea in a country where men dominate corporate boards in almost every industry.

Unmoved, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman threw a wrench in the deal, filing a lawsuit against the company partly out of concern that executives who failed to protect Harvey Weinstein’s accusers would continue to run the operation. Swiftly, the Weinstein Co. fired its president and chief operating officer, David Glasser, late Friday, only five days after the lawsuit. A statement announcing the firing was released to the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times.

The set of moves raised the question: Is putting women in charge of a company enough to guarantee an environment safe from sexual misconduct? In the wider business world, promoting more women to boards and the C-Suite is considered a critical step, but critics caution it is not enough, particularly when it comes to turning around a company so engulfed in scandal that it has become the poster child for sexual misconduct.

“Just having a female-led board is not enough of a solution. You need to disrupt the disease within the culture and that is an entire ecosystem change,” said Lisen Stromberg, COO of the 3 Percent Movement, an organization that promotes gender equality in advertising companies.

The $500 million acquisition proposal was put together by Maria Contreras-Sweet, a former U.S. Small Business Administrator under the Obama administration. She had no background in the film industry but her proposal beat out several offers from established entertainment companies including Lionsgate and Miramax, the studio formerly led by the Weinstein brothers.

The cornerstone of her vision was “reorganizing the company as a woman-led venture” that would create a “new model for how an entertainment company can be both financially successful and treat all its employees with dignity and respect,” according to a November letter to the Weinstein Co. board. That included establishing a female-majority board of directors, with Contreras-Sweet as chairwoman, and women investors controlling its voting stock.

Layers upon layers of complications

To be sure, a female-led board of directors at any prominent company would be a rarity.

In the last census by the Alliance of Board Diversity, women held about 20 percent of board seats at Fortune 500 companies in 2016. That was up from just under 17 percent in 2012, according to the study, which was conducted with Deloitte, an auditing, taxes and consulting services provider.

The number of women on boards does not tell the full story of what workplaces look like deeper inside company, or across an industry.

The census also found that women are slightly more likely to serve on multiple boards than men. That may suggest, the report said, that the pool of female candidates for top positions is shallower than the board membership rates would indicate, and that women are still rising slowly through the ranks of many industries.

Stromberg said the factors are numerous when she advises companies trying to promote women into leadership roles. She studies hiring trends and asks if women are languishing at certain levels. She looks at family leave policies, the types of assignments women get and whether their work is submitted for awards as often as their male counterparts.

“There are layers upon layers of complications that are necessary to be able to unpack whether this is an environment where women can thrive,” Stromberg said.

One recent case in point involved Fidelity, one of the few investment management firms led by a woman. The company last year fired two fund managers over allegations of sexual harassment and inappropriate comments. The company has several women in top executive posts, including CEO Abigail Johnson, who has led the company founded by her family since 2014. But Johnson has spoken openly of the challenges of recruiting more women into an industry where most fund managers are men, with Fidelity being no exception.

Still, Johnson won praise for her handling of the misconduct complaints, which included firing a star fund manager and taking the unusual step of moving her office from the executive suit several floors down to where portfolio managers and traders sit.

Marcus Noland, the executive vice president at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said putting more women on corporate boards makes a difference both in discouraging misogyny and in attracting more women into a company. One study conducted by the Peterson Institute, which analyzed data on more than 20,000 companies across the world, found a statistical correlation between the presence of women on boards and those in executive positions.

“I just can’t imagine a board that was female-led, where women were able to manage management, allowing this sort of misogynistic conduct to have gone on,” Noland said.

How deep the accusations go

Richard Levick, chairman and CEO of the crisis management firm LEVICK, said the gender of the board members is no guarantee of their commitment to an independent investigation into Weinstein’s conduct, including who might have been complicit.

“What were their plans for an independent investigation?” Levick said. “Are they aware of how deep the accusations go in terms of the enabling? You need to have a board that understands that the investigations will take you wherever the facts lead to.”

Schneiderman said he wanted to make sure that potential buyers knew about the “pervasive sexual harassment, intimidation, and discrimination” that occurred at the Weinstein Co.

The Weinstein Co. has not responded to requests for comments on the lawsuit. Weinstein’s lawyer, Ben Brafman, said many of the allegations were “without merit.”

Schneiderman insisted that any deal must oust executives who allegedly covered up misconduct. He said he was concerned about reports that Glasser, the executive dismissed Friday, would be named CEO of the new company. Without naming Glasser, his lawsuit said the company’s former COO had handled numerous complaints from employees against Weinstein, none of which resulted in an investigation.

Contreras-Sweet has declined to comment publicly on her proposed purchase. In her letter to the Weinstein Co. board, Contreras-Sweet asked the company to agree to a mediation process with Weinstein’s accusers and pledged to establish a litigation fund to supplement existing insurance coverage. Her proposal won the backing of activist attorney Gloria Allred, who is representing a number of Weinstein’s accusers. She said she was convinced of Contreras-Sweet’s commitment to the victims and criticized Schneiderman’s lawsuit.

Others were skeptical. Cris Armenta, a lawyer who is representing several of Weinstein’s accusers in a proposed class-action lawsuit, said there were unanswered questions, including who would monitor the fund and who would decide how to distribute it. She criticized the Contreras-Sweet group for failing to contact her.

“When I saw this deal going down and no one reached out to me, I thought, either they don’t have competent lawyers, or this is a show,” Armenta said. “It’s like buying a car and it needs work, and you don’t know how much work it needs, and you don’t even call the mechanic.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.