Facing inaction from the state, Philly politicians are trying new ways to avoid election drama

Philly election officials can only do so much to make elections work without state help. Two of those things: ballot drop boxes and better poll worker pay.

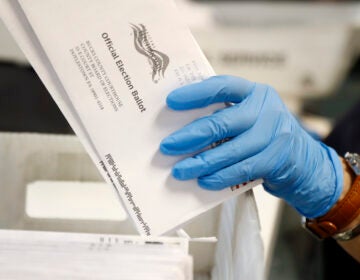

File photo: A new law in Delaware would make absentee mail-in voting legal for any voters in Delaware. Here, mail ballots for the 2020 General Election in the United States are seen before being sorted at the Chester County Voter Services office, Friday, Oct. 23, 2020, in West Chester, Pa. (Matt Slocum/AP Photo)

Philadelphia politicians are trying to fix an election dilemma.

Every year since Pennsylvania expanded mail voting, the city has been slow to publish election results. In a low-turnout municipal election year, like 2021, this isn’t a big deal. But in a midterm or presidential election year, these lags can be hugely consequential. In 2020, for instance, delays led to widespread theories about rampant election fraud where none existed.

The problem is primarily due to the fact that no county in the commonwealth is permitted to begin processing mail ballots before election day.

Lots of states process ballots ahead of time — it’s known as pre-canvassing — but Pennsylvania counties can’t do it unless the legislature and governor change a state law to allow it. There’s little opposition to the change, but after years of partisan disagreement on other election matters, state lawmakers haven’t passed it.

It’s an especially big problem in Philly because of the city’s size. Its results have a huge impact on elections, and it has to process significantly more ballots than other counties.

So now, Philly City Council, commissioners, and good government advocates are trying to come up with ways to improve what they can without help from the state.

Otherwise, says city commissioners’ spokesman Nick Custodio, elections will continue to be “essentially a race against time in order to get the results in before people start thinking there’s something wrong.”

Any improvements will likely be agreed upon jointly by the mayor’s office, city council, and the city commissioners. Recently, Councilmember Isaiah Thomas held a public hearing inviting elected officials at various levels of government, and advocacy groups, to testify on a range of election improvements.

Those potential improvements include printing ballots in more languages, finding a new method to decide candidates’ ballot positions — currently, names are picked out of a coffee can — increasing funding for election staffing, and creating more options for voters to drop off ballots.

Max Weisman, a spokesman for Thomas, says he’s hoping some of these changes can be made ahead of the May 17th primary, but that most will likely happen ahead of the November primary. On the ballot this year are candidates for governor, U.S. Senate, Congress, and the state House and Senate.

But Weisman acknowledges that there are lots of things the city can’t do without help from Harrisburg — like, for instance, allowing pre-canvassing.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is collect state stories and then bring it to partners in Harrisburg to show them that there’s a problem,” he said.

Al Schmidt, a former GOP city commissioner who now heads the good government group Committee of Seventy, said he thinks two particular improvements have the most potential to make elections in the city run more smoothly.

One is adding new funding for workers to count ballots and handle other Election Day logistics.

“Elections have changed a lot in the last couple of years. But one thing that has been consistent is, we need many thousands of people to work the polls on Election Day,” Schmidt said. “It’s a long day. And it’s a difficult day … Our election board workers are not compensated at the level they really deserve to be compensated at.”

The other, Schmidt said, is additional funding for mail ballot drop-off boxes.

Pennsylvania’s election deadlines work out in such a way that voters can apply for a mail ballot as late as seven days before an election. That doesn’t leave much time for them to receive a ballot, complete it, get it into the mail, and have it delivered back to the county elections office to be processed.

Schmidt argues, drop boxes help fix that problem without narrowing the application window for a ballot. Voters can use them right up until they’re locked at 8 p.m. on Election Day. However, they can be difficult to install because they need to be fixed to the ground, and they must be monitored by camera at all times.

Currently, the city has sixteen drop boxes in action. Custodio said two more may be in use by the May primary — one that was previously installed in Markward Playground but had to be closed off last election due to construction, and a new one in the southwest — but that the commissioners will likely need a new funding allocation, beyond their budget request for this fiscal year, in order to fund any more.

Commissioners, he said, plan to make a special request to council and the mayor’s office for election improvements beyond normal operations. Along with drop boxes and a dedicated camera system to monitor them, he says they want more satellite election offices so voters can have their questions answered, and potentially higher wages for election workers.

He noted, though, all this isn’t guaranteed to speed up ballot counting.

“That’s something you can’t just throw money at,” he said. “You can go to 24-hour shifts, but there’s only so fast you can count.”

Schmidt agreed. Ballot processing, he said, is complicated, no matter how long shifts are or how much workers are being paid. It involves opening ballots’ outer envelopes, removing inner “secrecy” envelopes, removing ballots, flattening them, and scanning them to actually count the vote.

It is a long assembly line and it takes some time,” Schmidt said. “Especially when we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of ballots.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.