Expanding the truth in ‘Broken Stones’ (InterAct Theatre Company)

A Marine sets out on a mission to recover antiquities in Iraq. A ghostwriter has her own ideas about the details.

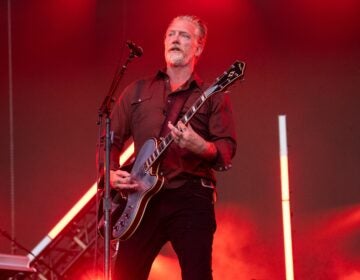

Rand Guerrero and Charlotte Northeast in InterAct Theatre Company's production of "Broken Stones." (Photo courtesy of Kate Raines/Plate 3 Photography)

If your head isn’t swimming when you come out of “Broken Stones,” you haven’t been paying attention. British writer Fin Kennedy’s tantalizing tease of a play, now in a world premiere from InterAct Theatre Company, spins and chips and grinds the truth until it’s no longer recognizable.

It’s also the most cynical play I can remember. More about that a few paragraphs down. First, let me tell you about the National Museum of Iraq, also called the Iraq Museum and in “Broken Stones,” the Baghdad Museum.

It has been one of the world’s greatest repositories of antiquities ranging back 7,000 years. Its former director, Donny George Youkhanna, described it to a Smithsonian magazine writer as the sole museum where you can trace the earliest development of human culture — “technology, agriculture, art, language and writing,” he said — in a single place.

In April 2003, weeks after U.S. troops invaded Iraq, the museum was looted. U.S. soldiers did not arrive to help secure it for several days after that. Cataloging at the museum had been lousy, but estimates place the number of stolen items at about 15,000.

Just after the looting a Marine reserve colonel named Matthew Bogdanos got permission from military superiors to assemble a team to identify the missing pieces, hunt them down and, in effect, return them to the world. Bogdanos had been a homicide prosecutor in New York and, among other things, a major in classical studies at Bucknell before he went to law school. He and the team were highly successful in their mission to restore the stolen artifacts, by all accounts. One of them is his own, a book called “Thieves of Baghdad” (Bloomsbury Publishing), written with ghostwriter William Patrick. Bogdanos donated royalties to the Iraq Museum.

“Broken Stones” is an account inspired loosely, then with more and more license, by what I’ve just laid out. It’s an elegant mind game as much as a play, beginning in a hotel lobby in L.A. — or is it New York? — where the story’s heroic Marine is named Alejandro Ramirez and he talks with an insufferably arrogant ghostwriter assigned to write his book. The roles are played with intensity by Rand Guerrero and Charlotte Northeast in a production that shimmers with tension under Seth Rozin’s fluid direction. It features an A-1 cast and Nick Embree’s handsome moving set that accommodates scenes in Iraq, New York, Hollywood and Britain.

Immediately, the insistent ghostwriter begins to reinvent the Marine’s story — first by changing his name from Latino to Italian, then by warping details one by one. She has a bizarre idea that the Marine’s story mirrors the Epic of Gilgamesh, possibly the oldest surviving piece of literature in the world.

The Iraq Museum holds a broken Mesopotamian table of Gilgamesh verse, but it’s been stolen in the looting. Gilgamesh was a strong-man king who tried to find a way to live eternally. In seeking the stolen tablet, the Marine is trying to find Gilgamesh. This, says the ghostwriter, is the story. Her motivation for what she conjures: Anything that sells more books than the accurate version, and maybe even movie rights. Who knows what else? They make plays out of movies these days, don’t they?

All along, the Marine is pushed into agreeing, thus silently conspiring with the “adaptors.” Fame becomes entrancing — also entrapping. By the time he cannot recognize himself in his public story, people who’ve bought the rights have taken it from him.

In his exploration of the way legends are manufactured out of facts, Kennedy’s taut play is complex writing with what amounts to moving parts: The story shifts as the legend of the Marine expands and the audience’s notion of what’s going on shifts with it. That’s highly effective playwriting. If anything gives me pause, it’s the cynicism I mentioned: Almost no one in “Broken Stones” seems to respect a fact.

You could argue that the world is shifting in that direction, which doesn’t make the world right. You can also offer a good case for the need to make a story work theatrically by shifting details here and there. The problem is, when true stories become historical fiction, how far do you go before people can’t tell the difference? In “Broken Stones,” the answer to that question is left to you to decide.

—

“Broken Stones,” produced by InterAct Theatre Company, runs through November 19 at the Proscenium Theatre on the side of the Drake Apartments, on Spruce Street between 15th and 16th Streets. 215-568-8079 or interacttheatre.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.