Escaping pirates: Wyeth artistic patriarch gets a retrospective

The father of Andrew Wyeth was the top illustrator of his day, but N.C. yearned to be a “pure artist.” The biggest retrospective of his work in half a century is now open.

Listen 2:00

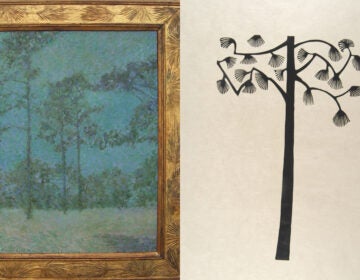

A visitor to the Brandywine River Museum takes a closer look at "Chadds Ford Landscape-July 1909," part of a retrospective of the work of N.C. Wyeth. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

N.C. Wyeth, best known for his vibrant illustrations of pirates for “Treasure Island,” begat Andrew Wyeth, one of America’s most beloved artists, who in turn begat Jamie Wyeth, also a highly regarded painter.

Jamie never met his grandfather, who died before he was born. He got to know N.C. by hanging out in his studio as a kid, learning how to draw from his aunt, the artist Carolyn Wyeth.

Young Jamie was surrounded by the paintings his grandfather made about Long John Silver, Robin Hood, and Wild Bill Hickok, as well as the roughly 800 illustrated reference books and the mountain of costumes, swords and guns N.C. had collected in order to paint adventures of pirates, knights, and cowboys.

“I would sit there for hours, and then I would walk back to our house, and my father would be there painting a dead crow,” he said. “I mean, that had no interest to me after living with Robin Hood for the last three hours.”

Wearing pirate breeches and mismatched long socks, Jamie walked the plank floor galleries of the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pa., where “N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives” is hung.

“He did all the knights of King Arthur, but he never left his studio in Chadds Ford,” he said. “He never went to Europe. Never went to the Caribbean where Treasure Island took place. It was all in his mind.”

Wyeth considered a painting depicting King Arthur astride his horse, commandeering his knights through an English moor. “That is from ‘King Arthur,’” he said. “But the background is Chadds Ford.”

N.C. Wyeth had been one of the most sought-after illustrators of his day, from the 1910s through the 1940s. He did adventure books, magazines, advertising, portrait commissions, even a mural for the Wilmington Savings Fund Society.

“He yearned to be, in the jargon of the day, a ‘pure painter.’ Not an illustrator, but a painter. Period,” said Christine Podmaniczky, who curated the exhibition in collaboration with the Portland Museum of Art, in Maine. “There was a dichotomy between painters and illustrators. It was illustrations, though, that paid the bills. He had a growing family.”

Podmaniczky pulled together 72 paintings and drawings by N.C. Wyeth for the show, the largest retrospective in 48 years. It is arranged chronologically, starting with his iconic paintings of cowboys and pirates, with their bold action and striking compositions.

While working on commissions for commercial clients, he was also painting on his own time, experimenting with fine art techniques of the day. Alongside “The Scythers” (1907), an illustration of farm workers for Scribner’s Magazine done in smooth brushwork and meticulously detailed landscape, is “Chadds Ford Landscape” (1909) a canvas made for no one in particular where he worked an impressionistic urge, punching daubs of paint into the sky like a layered collage of color.

A whimsical self-portrait shows N.C. Wyeth dressed in dapper costume — top hat, cape, and cigarette — set against a cubist background.

The flawed perspectives and bold colors of a crowded seascape, “The Harbor at Herring Gut ” (1925), reads like allegorical folk art.

“It looks like a group show,” said Jamie Wyeth moving through the exhibition. “He changed his methods so often. Impressionism, cubism, he was always experimenting. Much more so than my father and myself.”

N.C. Wyeth even tried his hand at tempera, a technique Andrew Wyeth claimed as his own. Jamie suspects N.C. just wanted to show his son that he could master it, too.

By the mid-1920, N.C. Wyeth was at the top of his field as an illustrator. It was then that he started to stretch himself as an artist, in earnest.

“I would say, really, from the death of his mother in 1925,” said Podmaniczky. “He felt he had not lived up to her expectations of him.”

Wyeth was born in Needham, Massachusetts, the oldest of four brothers. His mother encouraged his talent.

“His father was more traditional, working in various agricultural fields. He was a hay merchant in Needham, in Boston. He expected Wyeth to go into a more traditional field,” said Podmaniczky. “It was his mother who enabled him to come down here to Wilmington, to study with [Howard] Pyle. He felt that he had not lived up to the promise that his mother saw in him.”

From the perspective of his grandson, N.C. Wyeth’s best work were those illustrations, originally made as full-size canvas paintings before sending them to the printer to be reduced. Jamie Wyeth goes back to the adventure tales and sees brilliant composition, tremendous energy, and a genius sense of color. He believes his grandfather’s best work is what he is best remembered for.

“My mother always told me a story when she first met him,” said Jamie. “She was 17 when she married my father. She said, ‘Oh, Mr. Wyeth, I love your illustrations of Treasure Island.’ And he said, ‘You’ll outgrow it.’ ”

“Of course he was dead wrong.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.