‘Glad it all came together’: First Wilmington residents move into revitalized Riverside housing project

The new homes mark a dramatic rebirth of decaying and partly-boarded housing development built in the late 1940s for returning white veterans of World War II.

The 600 homes will be built over a four-year period. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

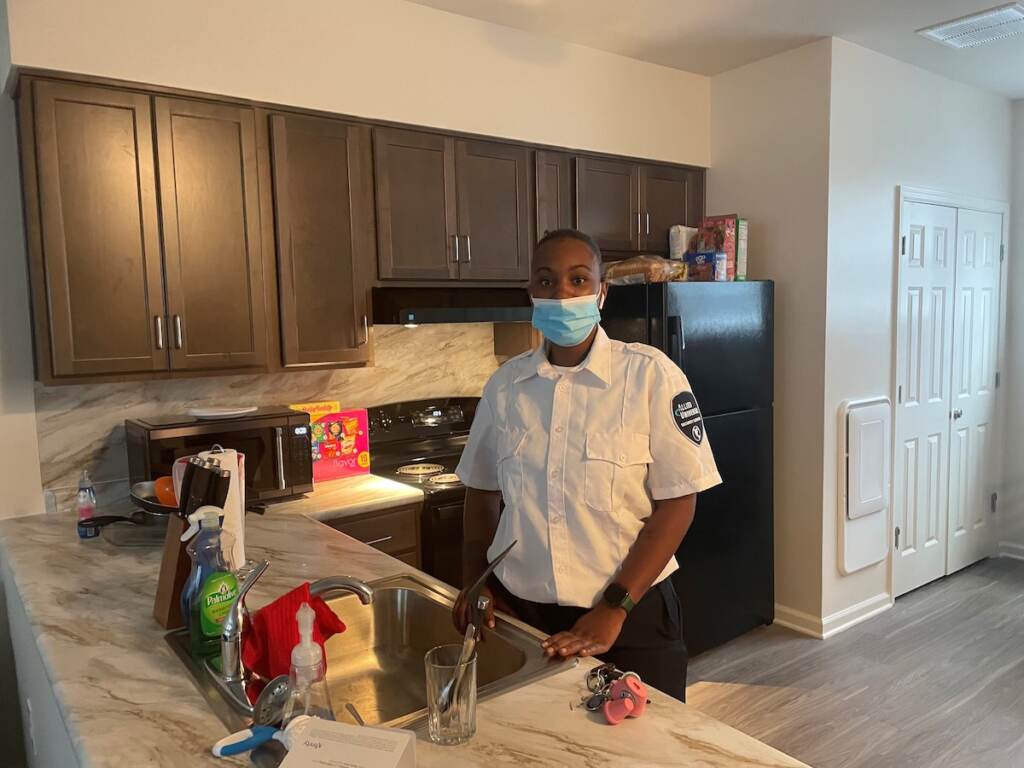

Standing in the kitchen of her sparkling new two-story townhouse, Brittany Rollins gushes about her good fortune in moving from the long-decaying Riverside public housing project across the street in northeast Wilmington.

“I have central air, I have a dishwasher, I also have nice appliances,’’ Rollins, a Bank of America security guard, said this week after returning home from work. “I have a washer and dryer upstairs. I have one and a half bathrooms, two bedrooms, storage out back. Lots more space than I had. So I’m excited.”

Rollins is one of 14 Riverside residents who have moved over the last month into Imani Village, which over the next four years will become a 600-home development that seeks to transform one of the city’s most impoverished areas.

Imani Village is just yards away from the squat brick buildings built in the late 1940s for white veterans of World War II. Many of those Wilmington Housing Authority units are now vacant and boarded up, and almost all tenants in the 240 occupied units are Black men, women and children. Eventually, those homes will be razed to make room for the rest of Imani Village.

Imani Village is promising a brighter future for residents like Rollins, who says she’s paying roughly $900 a month after a public subsidy. The complex offers subsidized units based on income, but also will rent at market rates, such as the three-bedroom homes that go for $1,300 a month.

Logan Herring, who heads the REACH Riverside coalition that is overseeing the area’s rebirth, says Imani Village offers a way out for families that for too long have been “forced to live in communities of consolidated poverty.”

Herring says Riverside is entering “a new chapter for Riverside residents — one in which children are proud to call their community home and families are able to move from financial distress to success” and perhaps home ownership.

That’s the hope of Rollins, who has a 10-year-old daughter and is working to improve her credit rating to buy a home someday. She says her new place in Imani offers that bridge.

Like many longtime Riverside residents, Rollins admits being skeptical over the years when officials spoke about plans to build new homes for residents, like they did nearly two decades ago in the high-crime Eastlake development across Northeast Boulevard.

But the $300 million Imani Village progressed steadily after the plan was announced about three years ago, and now she’s a resident.

“I didn’t expect to move as soon as I did, but I’m glad it all came together,’’ Rollins said.

Riverside now “looks like it’s on the up and up’

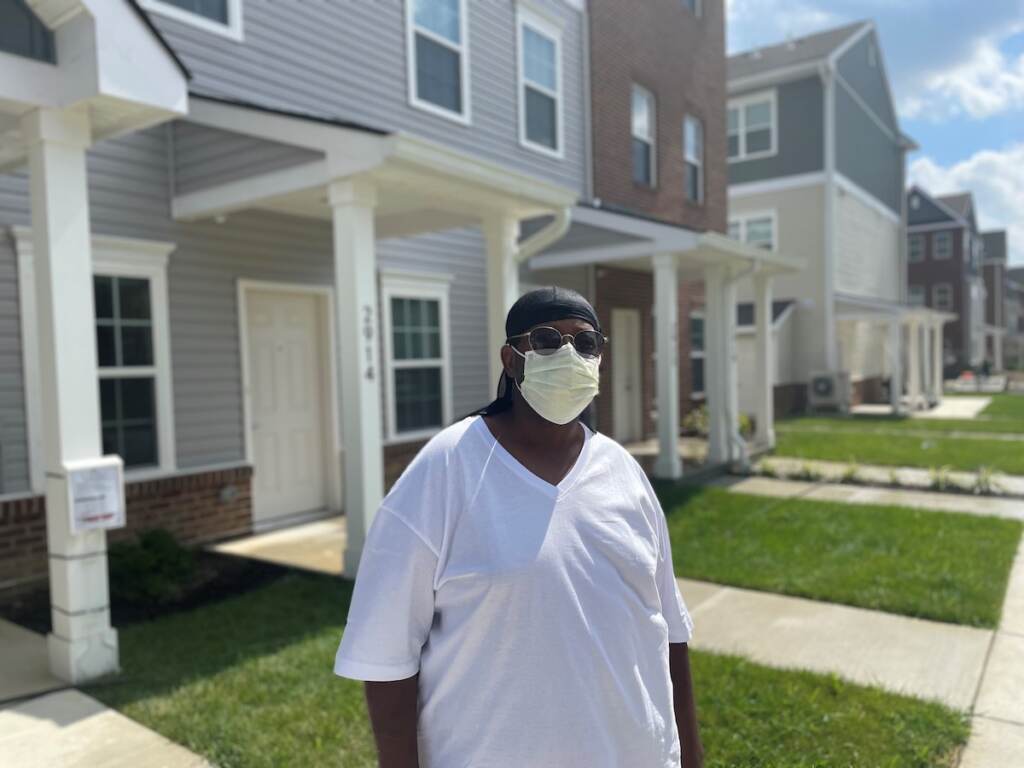

Imani Village is also drawing interest from residents outside of Riverside. Rashid Brison drove there to check out a possible home for his sister, who has four young children and minimal financial resources.

“I like what they’re doing in the projects. It’s not as bad as he used to be,’’ said Brison, who lives in southwest Wilmington. Now that new homes are finished and more are being built, “it looks like it’s on the up and up.”

Mike Phares, who lives near downtown, checked out Imani Village for himself and his mother. He picked up a brochure and watched construction crews at work.

“I think it’s going to be a wonderful, wonderful place,” Phares said.

But Regina Green, who drove Phares to Imani Village, said she’s not interested. She once lived in a home that was torn down years ago on land where the first homes are being built, but said it bothers her that residents can’t barbecue right outside their house.

“I mean, it’s beautiful,” Green said. “But for me to come back here, I don’t think so.”

Jen Lienhard of REACH Riverside said Imani Village will soon have “gazebos with safety protocols in place to manage hot coals” for barbecuing. The gazebos and green spaces will serve as community spaces for picnics and other large outings, she said.

Lienhard says Imani Village aims to be a model of “gentrification without displacement,” but some current residents question whether that’s true. In the grass and dirt courtyard behind one home, amid several boarded ones, a few expressed that sentiment.

None would identify themselves, saying they feared being targeted by the housing authority, but all believe the red tape required to get into Imani Village will effectively ban many of the current tenants.

“If they really put in residents back there from there,’’ one man said, gesturing across Bowers Street to Imani Village, “and they’re not gentrifying it and pushing them out, then that’s all cool. Because a lot of people here were born and raised here, they’re proud of their environment, they love being here.”

He’s heard that residents who have failed inspections in their current unit might be disqualified.

“I feel like they’re using a whole lot of excuses so they don’t have to put people back there,” he said.

Leinhard countered that residents are welcome to participate in the EMPOWER program — which stands for Economic Mobility Places Ownership within Everyone’s Reach.

The program “provides trainings, workshops, and personalized coaching to ensure that Riverside families have the tools they need to achieve financial freedom and build generational wealth,’’ she said

“Our navigational coaches create individualized plans with residents to ensure that when the opportunity to move into Imani Village becomes available, they are financially ready.”

The overarching goal, she said, is to create a livable community. To that end, the Kingswood Community Center down the block has a $42 million renovation plan in the works. Last year, Kingswood also opened a satellite medical facility. There’s also hopes to draw a large-scale grocery store to Northeast Boulevard, which mostly has fast food eateries or convenience stores.

“It doesn’t work to have all of our subsidized housing in one concentrated area without the social services that are required to be successful,” Lienhard said. “Things like having community space, having a grocery store, having access to good jobs, and really the tent poles that create a community that lasts.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.