Why won’t Delaware let medical weed dispensaries kick off retail sales, like New Jersey and Maryland did?

One medical provider says dispensaries already have the infrastructure and know-how to provide safe, legal products. Some say that would be an unfair advantage.

Listen 1:52

At left, Bill Rohrer, co-owner of The Farm, works with business partner Bill Owens in one of the medical marijuana growing facilities. (Courtesy of Bill Rohrer)

When New Jersey and Maryland legalized retail sales of recreational marijuana, those states permitted medical dispensaries to be the first stores to sell weed to the general public.

Their neighbor Delaware, however, isn’t letting that happen. Instead, lawmakers created a laborious, lengthy process that effectively prevents any retail stores from opening until late 2024, perhaps even into 2025.

The new laws that took effect in late April — one allowing people age 21 and over to possess up to an ounce of weed and another creating a regulated growing, testing, manufacturing, and retail market — exposes users to somewhat of a legal conundrum, however.

That’s because to buy marijuana, for now users have to get it the old-fashioned way — from someone breaking the law by selling it, or by buying it legally across the state line and breaking the law by bringing it back to Delaware.

Earlier versions of marijuana regulatory bills in Delaware would have allowed medical dispensaries to kick off recreational sales. That provision was removed, however, after opposition from medical users who worried that there would not be enough supply, state Rep. Ed Osienski said.

“We heard major pushback from patients,’’ said Osienski, a Newark Democrat who sponsored the bills whose passage culminated a six-year crusade by legalization advocates. “They said that the medical compassion centers could barely provide the patients what they needed let alone to sell some of their products to recreational users.”

Osienski and Zoe Patchell of the Delaware Cannabis Advocacy Network said the new law, although it delays the opening of retail stores, will ultimately create a stronger, more competitive market that will benefit users with decent prices.

Another reason retail sales will be delayed is that the state has not yet set up mechanisms to collect the 15% sales tax from the 30 retail licensees the law authorizes, and to allow oversight audits of the businesses.

State finance secretary Rick Geisenberger said the process will be a lengthy one for Delaware, which doesn’t have a sales tax for any other product. Officials might have to seek bids from vendors who can provide the software and expertise for the taxing and audit system.

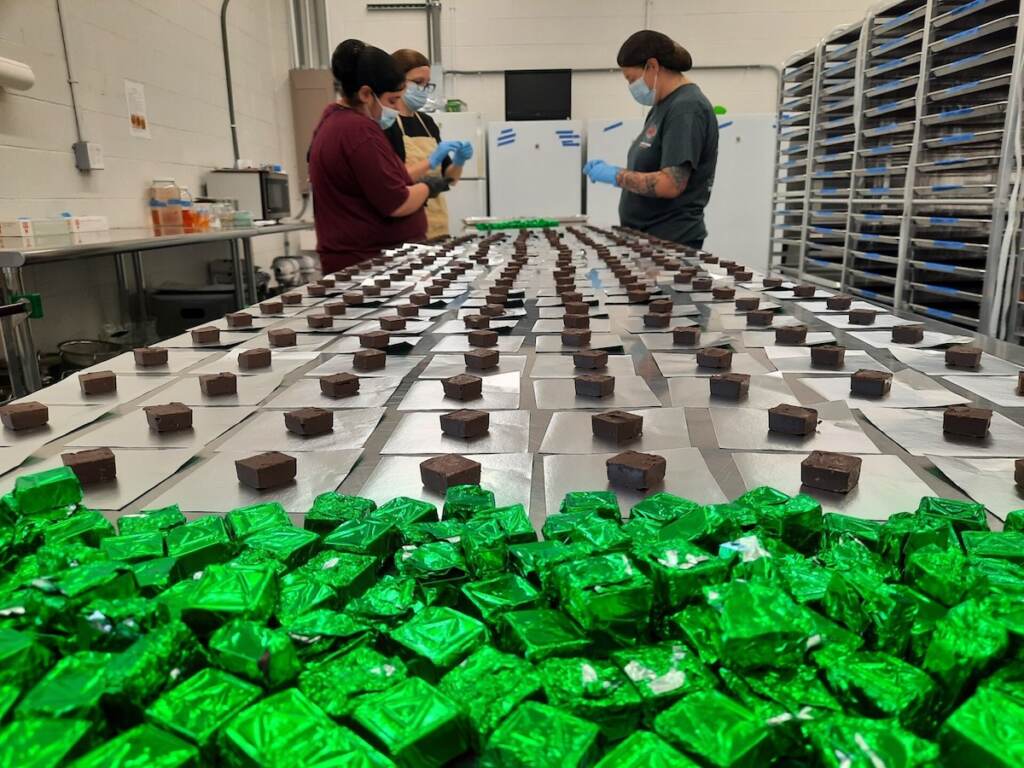

But Bill Rohrer, who owns The Farm, a medical marijuana company with two growing operations and two dispensaries, thinks Delaware’s approach to kicking off retail sales is just ludicrous.

He charges that while Delaware is creating regulations and going through the time-consuming licensing process, officials are allowing weed dealers to keep breaking the law instead of doing what New Jersey and Maryland did.

“It feeds the illicit market is what it does,’’ Rohrer said of the regulatory law.

Rohrer, who said he’s a member of the new Delaware Association for Cannabis, says the state’s six medical marijuana licensees can easily help kick-start the retail market. In Rohrer’s view, medical providers can start retail sales in their dozen or so facilities while also seeking an official recreational retail license along with other applicants.

“We are a very simple solution for the state to temporarily or however, provide products to the citizens of Delaware, because we already have that infrastructure,’’ Rohrer said.

“It took one to three years to really get set up. So when you do control-alt-delete on the entire infrastructure that the medical marijuana business has set up, and you just want to start all over, it just doesn’t make sense from a public policy perspective or a business perspective.”

Weed users ‘can wait a little longer’ for competitive legal market

Patchell counters that doing so would be counterproductive to creating a solid, competitive market that will provide 10 of the 30 retail licenses to “social equity” applicants. Those licensees are reserved people who have lived for five of the last 10 years in an area disproportionately impacted by marijuana prohibition enforcement or had been convicted of a marijuana crime, except for high-level dealing or selling to minors.

She said medical dispensaries are already an “oligopoly” and would dominate the market if given a head start to sell retail weed.

“Allowing these companies to have the anti-competitive privileges would severely jeopardize the medical cannabis and adult use market,” Patchell said. “It would undermine any new small business or social equity applicants trying to get into the new market.”

Patchell also said it’s worth waiting more than a year to issue retail licenses, even if that means illegal dealers retain control of the market.

“Consumers have waited nearly 90 years for legal cannabis sales, and they can wait a little longer,’’ she said.

She believes that if the medical marijuana companies take control of the recreational market, prices of legal weed could rise in the absence of healthy competition.

“Quite frankly, it’ll set the entire Delaware cannabis market up for failure because adult use consumers are simply not gonna pay $300 to $400 an ounce,” Patchell said. “They’re gonna continue to go to Joe Schmoe on the corner who sells it for significantly less.”

‘If you have that delay, you create this void’

Wilmington attorney Peter S. Murphy represents cannabis clients in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and other states. He sees New Jersey and Maryland as positive examples when compared with New York, where illegal distribution became widespread in the 19-month period between legalization and distribution of the first legal licenses in November 2022.

In New York city, shops selling stickers have been able to illegally distribute weed by offering it as a “gift” for legal purchases, according to news reports. City officials estimated this year that there were 1,400 “sticker shops.”

“If you have that delay, you create this void where demand is there, the existing medical providers can’t meet it, they’re not allowed to sell to them,” Murphy said. “So those sales come from the illegal market and in New York, within a matter of months, thousands of illegal dispensaries.”

Murphy says the overarching goal should be to create regulated, safe, and reasonably priced products from any and all legal sources to compete with the illicit market.

But in the meantime, the lawyer said that “allowing existing medical licensees to serve that market … makes a lot of sense, and it doesn’t necessarily take away from future opportunities.”

Osienski counters that a guaranteed license or even a conditional one until the official licenses are issued would give medical providers a head start that could push out other potential sellers. He thinks it’s an unnecessary measure because medical providers will likely be some of the first to be granted licenses — once they’re available to everyone.

“I really think that the compassion centers will easily go through this process with the experience they have,” he said. “I don’t know what people are worried about.”

He says the process of creating regulations and procedures is moving ahead of schedule with the appointment of former Safety and Homeland Security secretary Robert Coupe as marijuana commissioner.

Gov. John Carney, a staunch foe of legal weed who let the bills become law without his signature after vetoing a legalization statute last year, had until the end of September to name a so-called weed czar, but did so in June.

Coupe has been at work for nearly a month, and has visited Roher’s facility and met with Osienski while he assembles a staff and begins drafting regulations to govern retail sales.

Should the regulations get established sooner than expected, Osienski said that when lawmakers reconvene in January, he’s willing to introduce legislation to accelerate the licensing process and pave the way for earlier retail sales.

“The faster we get it up,’’ Osienski said, “the better it will be for Delaware consumers.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.