For Delaware artist Robert Straight, inspiration begins with the canvas itself

Have you ever looked at a blank canvas? Really looked at it? Those tiny little threads, woven together, it's that pattern gives Robert Straight his inspiration.

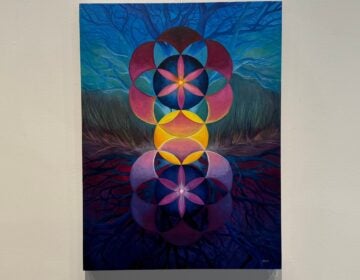

Robert Straight didn’t want to paint landscapes, or portraits. “I wanted to try and invent my own world,” and he’s been doing it for over four decades.

Have you ever looked at a blank canvas? I mean really looked at it? Tiny little threads are woven together. They go on and on, up and down and sideways flowing across a blank canvas.

It’s that pattern, those lines where Robert Straight gets his inspiration. “The way that it’s woven. You have these threads that could be woven forever.”

It’s a sense of “nirvana” that he gets from the canvas. “Something in the physical world can suggest, you know going own forever and ever,” Straight said.

From there he uses paint and brushes and even math to create his work. “I’m really thinking about color a lot and the application.” He uses all kids of brushes, and even drafting tools like French curves to create his worlds.

But it’s the brush stroke itself that carries the most weight. Recreating the lines of the woven canvas with the paint itself. “Even though you don’t see the canvas, it’s like remaking the canvas, that’s a big part of what I do.”

One idea leads into the next. “That sort of led to this idea of what about shapes that have certain aspects of math.” His paintings are not on traditional shaped canvases. Most of the paintings have either seven or thirteen sides to them. “That in itself would perhaps be the start of a painting,” he said.

Change came when he started working with wooden slabs. The shape became king in these pieces. “The shape became important, multiple shapes kind of kissing each other.”

From there he wanted to work more with 3D objects, so he started making sculptures made of containers and newspaper. “I started thinking about these containers. At some point a designer made those things.”

He wanted something that at first people wouldn’t recognize, but perhaps “they’ll feel like somehow they know that that’s something I’m familiar with.”

The sculptures are covered in paper mâché. Of course in Robert’s case even the paper has significance to the work. The paper mâché was torn newspaper, and all the paper in each sculpture comes from that day’s newspaper. “The sculpture becomes a record of that particular day of the year and even though you cant read the newspaper, it’s an indication of history.”

Ultimately, Straight hopes you are puzzled when you look upon his work, you aren’t quite sure what you are looking at. He also hopes you question that. “I hope that question of what am I looking at also makes them start thinking about painting and what painting can be, or what it might mean.”

He’s worked in many different types of art using many different types of materials over the years. It’s important for him to evolve.

“It’s important to keep evolving and changing and pushing yourself always questioning where you are and how it can go beyond that.”

You can see samples of all of Robert’s work in the slideshow below.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.