Daylighting project reveals a hidden creek

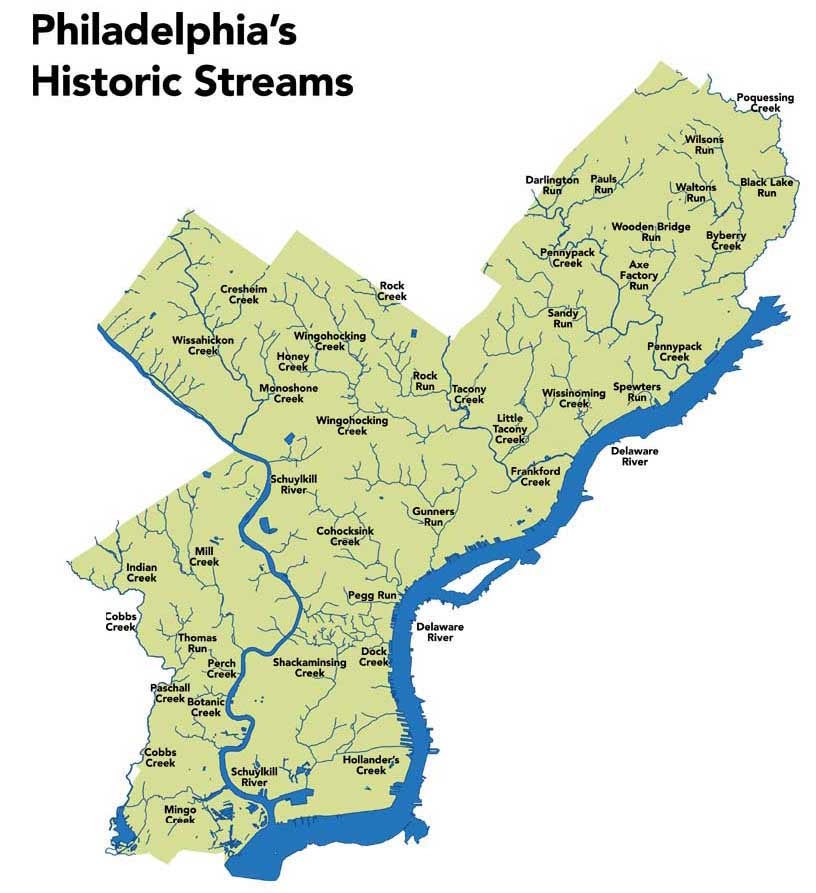

About 700 feet of the West Branch of Indian Creek never sees daylight. For more than 100 years, it has run through a box culvert in Overbrook’s Morris Park.

The Philadelphia Water Department and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are now taking the creek out of its dark tunnel in a joint project that will not only create more open stream habitat, but significantly reduce the number of times untreated human waste winds up in Indian Creek.

The name Overbrook hints at the reason Indian Creek and most of the streams that once flowed through Philadelphia now flow through pipes, said PWD Office of Watersheds Environmental Engineer Rick Howley. Overbrook is “built over top of stream systems,” he said.

Philadelphia once had 283 linear miles of streams, but now all but 118 miles are buried.

Burying streams in pipes freed land for development. During the city’s development, streams and rivers were the means of carrying sewage away. Burying the streams was also a strategy to deal with the health problems they presented.

Indian Creek flows into Cobbs Creek, which flows into Darby Creek. While the city doesn’t want to put sewage in creeks anymore, tht still occurs during significant rain storms.

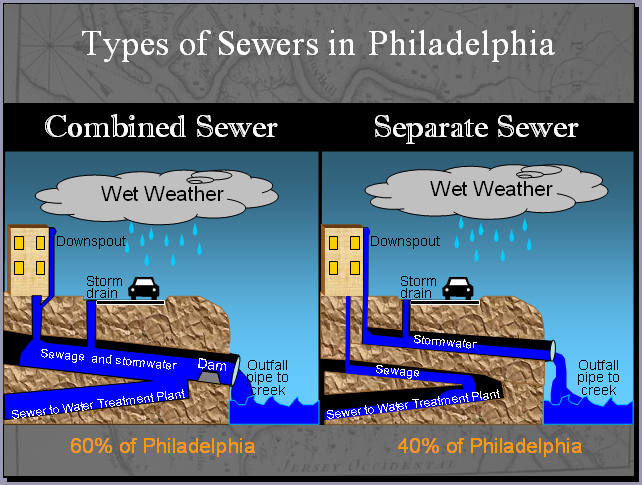

According to the water department’s Green City, Clean Waters website, 60 percent of the city has sewers that carry both storm water runoff and sewage – known as combined or one-pipe systems. In a combined sewer system, both storm water and sewage go to the water treatment plant. But in hard rains, the capacity of the pipes is overwhelmed, and to help prevent flooding of streets and homes, some of the untreated rainwater and sewage flow into outflow pipes, which lead directly to rivers and streams.

There is a combined sewage outflow that releases excess run-off water – and sewage – into Indian Creek. This currently happens about 24 times every year, Howley said.

While the West Branch project will remove the stream from the box culvert, it will only close the culvert at one end, explained Erik Rourke, strategic planner with the Army Corps of Engineers Philadelphia Division. When it rains hard, the excess capacity from the combined sewer system will fill up the old culvert. Only if that becomes full will the water and untreated sewage run into the creek, Rourke said. “We’re going to have 180,000 gallons of storage,” he said.

That is projected to reduce the amount of times sewage runs into the creek from about 24 times per year to three times annually, and from 2.9 million gallons of overflow to 1.2 million gallons.

It will take about three months for the West Branch of Indian Creek to be taken out of the pipe and rerouted, with a new connection to the creek’s east branch. Within 12 months, the rest of the $3-million-plus project, including the creation of natural-looking stream banks planted with native vegetation, will be complete.

This means more habitat for animals – relatively large ones like birds, deer and squirrels, and relatively small ones like caddisfly and small fish. The natural stream banks will have more water-absorbing power than the big pipe does, and that translates into less run-off.

The improvements will make Morris Park more beautiful for human visitors, said Valessa Souter-Kline of PWD’s public affairs division. “It’s also an exciting project because this is near the headwaters” of the creek, she said. Improvements at the top have an impact on the entire watershed downstream, she said. And it’s not just less sewage and related coliform bacteria. If the headwaters have invasive species, their seeds travel in the water and those plants can be spread downstream, she said.

On a recent visit to the site, a portion of the East Branch bed was dry, with pipes temporarily carrying the water downstream so that work could be done at the juncture of the two branches. A large pile of boulders stood to one side, ready to become part of a stone wall that will help protect the area from erosion that could otherwise take place at the juncture. What looks like a dirt road covered with an unbelievable amount of mud is the future track of the West Branch – cleared of vegetation, but still in need of grading to allow the water to flow downhill.

Before long, the West Branch will be dammed, and the water sent downstream through pipes so workers can straighten a portion of the current creek bed and attach it to the new bed they will create to join it to the East Branch. The damn will then be taken down, and the creek will flow in the open air again.

This is not the creek’s historic path. That wound through an area that has since been developed. This is the water department’s first creek daylighting project, Howley and Souter-Kline said. While they hope others will be done, that’s impossible for the vast majority of the buried streams, she said. They lie deep beneath buildings as roads, and there’s no room for a waterway in a developed neighborhood.

The water department is using other means to combat the overflow problem, all directed at keeping water from entering the system, or slowing it down. These include stream bank restorations along the creeks that are above ground, the creation of wetlands and rain gardens, the planting of street trees, the use of non-porous pavement, and even encouraging residents to save rain water in rain barrels and use it to water plants. Learn more here.

Old planning maps show the West Branch of Indian Creek was slated to have development built over top of it, too, Howley said. That didn’t happen only because the Morris family donated the land that is now Morris Park.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.